University-based social impact programs go by many names—centers for social impact, programs on social entrepreneurship, and social innovation initiatives. But regardless of their title or focus, all have experienced explosive growth over the last decade. Ten years ago, only a handful of schools invested in social impact education; today, almost half of the top 50 business schools in the world offer some kind of program.

Both Skoll Foundation CEO Sally Osberg and the late Pamela Hartigan, then-director of the Skoll Centre for Social Entrepreneurship at Saïd Business School, The University of Oxford, were deeply intrigued by this groundswell and partnered with The Bridgespan Group to analyze the trend. Our global team focused our research around the work of leading university-based social impact centers, conducting more than 30 in-depth interviews with experts in 8 countries, inside and outside academia. After much discussion of the findings, we all came away with complementary perspectives on the future of social impact education. Osberg observed:

The Future of Social Impact Education in Business Schools and Beyond This series, produced in partnership with Oxford’s Skoll Centre for Social Entrepreneurship, will share global perspectives about potential shifts in social impact education.You'll get email alerts when there is new content in this series.

This series, produced in partnership with Oxford’s Skoll Centre for Social Entrepreneurship, will share global perspectives about potential shifts in social impact education.You'll get email alerts when there is new content in this series.It’s all too clear that the challenges confronting humanity and the planet are fast outstripping the capacity of institutions across all sectors—government, business, and civil society—to solve them. At the same time, growing numbers of young people, enlightened leaders, and citizens around the world are signaling that they are not content to stand by and wring their hands.

Similarly, Hartigan reflected:

There is a fortuitous virus that is “infecting” an increasing number of young adults and mid-level professionals who want to pursue careers with positive social impact, and we are excited to be part of the collective pathogen of learning institutions highlighted in this report. But how much faster can we spread this collective virus, given the inertia that characterizes academic institutions?

No longer a niche concept, our research found that social impact centers have successfully moved beyond the “1.0” stage, and are increasingly considered “must-have” offerings on the crowded radar screens of deans and senior faculty sponsors—not to mention wealthy alumni. Led by extraordinary demand, center leaders around the world report feeling pulled to serve a diverse range of stakeholders—including students, professors, researchers, practitioners, and even philanthropists and governments—in the face of a variety of sprawling societal crises.

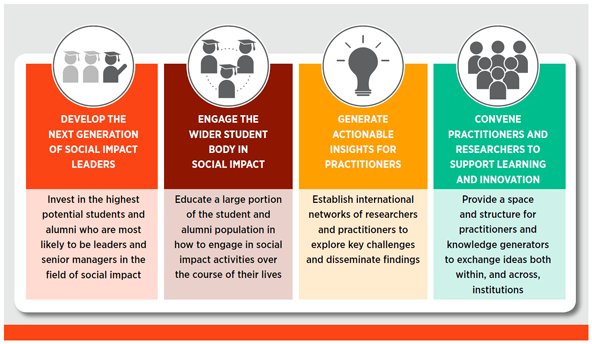

To be sure, there is a solid base to build on. Over the past decade, university-based social impact centers have successfully pursued four activities: developing the next generation of social impact leaders, engaging the wider student body in social impact, generating actionable insights for practitioners, and convening practitioners and researchers to support learning and innovation.

University-based social impact centers can build on areas of historic strength. (Image courtesy of The Bridgespan Group)

University-based social impact centers can build on areas of historic strength. (Image courtesy of The Bridgespan Group)

But the strains on existing centers are evident. Ten years ago, merely establishing such a center was a distinctive act of leadership; now, it’s viewed as table stakes. Cross-departmental by definition, they don’t have natural homes and defenders. And with so many stakeholders, centers report feeling compelled to provide “a little bit of everything” programming—including business plan contests, social enterprise 101 classes, and student extra-curriculars—all while recognizing that they could probably realize significantly more impact if they were to provide a minimum threshold level of services across their constituencies, and then focus intentionally on a distinctive big idea or project that moves the field forward. Looking ahead, they are keen to explore what “2.0" might look like across four areas:

- Educating and preparing a broader, blended range of student talent for social impact work across the social and private sectors. Exciting programs are blending nonprofit, private sector, and government work, as well as research opportunities for students to prepare for next-gen careers.

- Driving deep expertise as the basis for dramatically propelling actionable research. New collaborative research and learning programs blend practical and academic perspectives, and create areas of specialization that advance the field.

- Defining social impact as a structured academic discipline. To bolster teaching and research ranks in a field of limited traditional tenure opportunities, universities are reaching out to experienced faculty in other disciplines who are looking for meaningful applications of their research, as well as practitioners willing to make a career shift.

- Developing and tracking measures of student impact in the world. As rankings have (in the view of many university leaders) contributed to unproductive behaviors in higher education globally, some centers are contemplating advancing more robust metrics of student impact, which can assign a positive value to the social impact their graduates create in the world.

Growing global interest in social impact is raising the bar on the role university-based social impact centers must play—stretching them even thinner—and interviewees cited the real opportunity cost that comes with broadening their reach. As the rhetoric and promise of these centers’ impact increasingly figures prominently in their home school’s branding efforts, finding a distinctive area of impact and voice is critical. Rather than do more of everything, the best strategy—for even the biggest and best-funded centers—may be to establish a baseline level of services for all constituents, and then focus on making significant progress within one of these distinct areas over a 3-5 year time frame. Most programs are still comparatively new, especially in the context of their home universities, so they have the opportunity to distinguish themselves from the outset.

In her preface to the report, Osberg issues a challenge for herself and all of us:

Will educators and their institutions seize this opportunity? Can they re-tool their curricula, re-configure their pedagogical practices, and re-make their structures fast enough to meet the demand of students determined to align their career and life choices with the imperative to make a meaningful difference in the world? Our purpose [with this report] is to highlight both the current state of [centers] like ours and to encourage us all to seize this moment, to take stock of our challenges and this unprecedented opportunity. The clock is ticking, with no time to lose.

This report is intended as a conversation starter for all leaders who care deeply about the promise and potential of university-based social impact centers. We hope that the diversity of voices engaged in this series will further improve upon these ideas, and point the way onward.

Conclusion (by Georgia Lewis)

Over the past few weeks, we have heard a variety of viewpoints on how educators might “re-tool,” as Osberg suggests. Reviewing the perspectives of the contributing educators and experts left our team at the Skoll Centre with some important takeaways.

First, we cannot underestimate the importance of inclusive classrooms. Alastair Wilson of School for Social Entrepreneurs notes that universities are by nature meritocratic and set up to serve the privileged few. Francois Bonnici, director of the Bertha Centre at University of Cape Town’s Graduate School, built on this notion, expressing that social impact educators should disrupt their own systems and diversify their student body to achieve greater social impact, and pursue an approach that gives students a chance to challenge their assumptions and learn from those with radically different life experiences.

Skoll Scholar Macarena Hernandez do Obeso makes a presentation at Prospera, Mexico.

Skoll Scholar Macarena Hernandez do Obeso makes a presentation at Prospera, Mexico.

Contributors also discussed rethinking student incentives—moving away from traditional business plan competitions, for example, and instead rewarding students for deeply understanding the problems they try to address. Alan Harlam and his team at Brown University’s Swearer Center suggested ways to incorporate the voices of the communities students aim to help in the classroom, and human rights lawyer Baljeet Sandhu highlighted the value of hearing from those who have lived with a social problem. Harlam noted that such approaches improve not only the viability of proposed solutions, but also students’ learning experiences.

The series also explored core competencies social impact educators must develop in their students. Guerrilla Foundation’s Romy Kraemer noted that these include self-reflection, empathy, boldness, and resilience. Rather than encouraging every student to become a social entrepreneur, she suggested that educators offer coaching, long-term advisory offerings, and experiential learning to students so that they can develop a deeper understanding of how to apply their unique strengths to social change. Duke University’s Cathy Clark and Carrie Gonnella believe that the field needs tri-sector impact investment leaders with appropriately diverse skillsets, and that universities should apply a competency-based development approach to one of the most popular MBA careers of today.

Ultimately, we walk away excited by the gains made by social impact educators, while also noting “what got us here won’t get us there.” Educators have the opportunity to actively shift our approaches, with the aim to developing leaders who can address ever more intractable and nuanced social and environmental problems with thoughtfulness and skill. We hope these conversations will continue and amplify, and ultimately enable educators to take action.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Alison Kelley & Susan Wolf Ditkoff.