The United Nations made headlines around the world in September 2015 when it adopted an ambitious set of 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) that aim to end extreme poverty, protect the planet, and ensure health and prosperity for all by 2030. Delivering on these goals won’t come cheap. The UN estimates that it will require an additional $2.5 trillion in funding each year above what is currently being spent by government, business, and philanthropy.

Government and business have the deepest pockets and, no doubt, will shoulder the largest financial burden. But they cannot do the job alone. Philanthropy also has a critical role to play. It brings not just much-needed money, but often a willingness to support big thinking, innovation, risk-taking, and collaboration.

The power of those contributions is particularly evident in philanthropic “big bets” that aim to speed progress on specific social issues, such as pediatric AIDS or quality education. The Bridgespan Group’s research has established the outsized role big bets can play in propelling social change. Building on that work, we set out to research the flow of big bets to areas targeted by the SDGs—hoping to discern patterns that could inform future philanthropic efforts.

UN Foundation President and CEO Kathy Calvin has elevated the need for more research of this sort, pointing to insufficient data as a barrier to more rapid progress on the SDGs. “A core challenge within the philanthropic community is that there isn’t enough data on where the dollars are flowing vis-à-vis the SDGs, or enough transparency on what impact the dollars are having,” says Calvin. This Bridgespan study is part of a constellation of efforts aiming to fill that void and help funnel more dollars, more effectively to achieving the SDGs.

Tracking Donor Big Bets Aligned with the SDGs

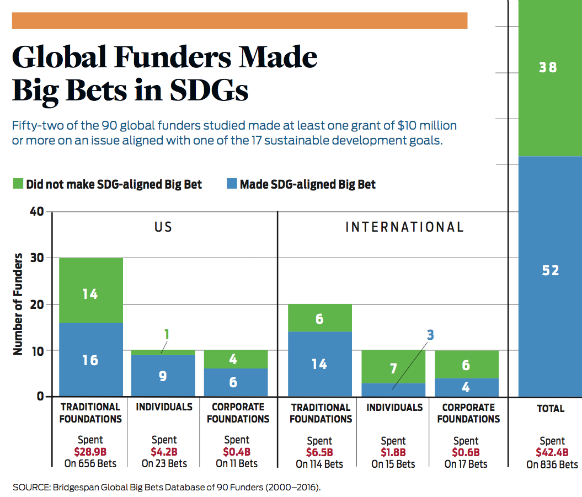

Bridgespan began by identifying and researching the big bets made by 90 leading US and international philanthropists. We sought a representative sample of three types: traditional foundations, wealthy individuals, and corporate foundations. For each, we identified grants of $10 million or more between 2000 and 2016. Although the SDGs did not take effect until January 2016, and thus did not directly motivate the philanthropic activity, the 17 goals provided a useful framework to categorize them.

For each big bet, we made a judgment call about which SDG to categorize it under, given that the goals are interrelated. Among the 90 funders we studied, 52 made big bets aligned with the SDGs. They collectively deployed $42.4 billion via 836 big bets over the 17-year timeframe of our research.

Not surprisingly, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, which gives away six times more money than the next largest global funder we studied, tops the roster with just over 500 SDG-aligned big bets (about 60 percent of the bets in our database), totaling nearly $20 billion.

More than half of the other funders we researched also made big bets in SDG areas. Most did so outside of their home countries, reflecting a broad commitment to global development issues. Moreover, these funders sharply increased their financial commitment to SDG-aligned big bets even before the UN ratified the new goals in September 2015. When we compared five-year spans ending in 2010 and 2015, pledged spending rose 84 percent.

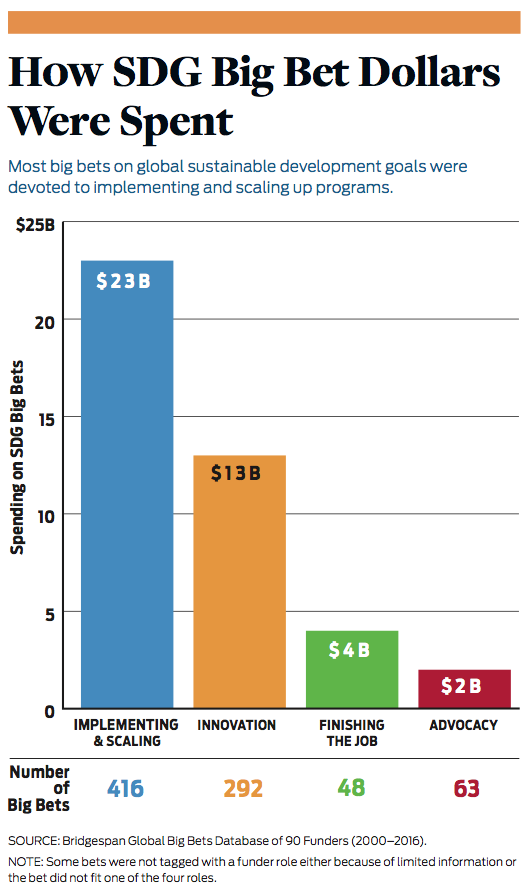

The amounts pledged tell only part of the story. How the donors deployed the funds is equally important. Despite the diversity represented by the 836 big bets in our database, we found that funders’ efforts clustered around four broadly defined roles: developing and testing innovative solutions; implementing and scaling solutions that work; collaborating to finish the job; and advocating for policy change.

- Developing and testing innovative solutions | Grants targeting innovations accounted for nearly a third of the $42.4 billion in SDG-aligned big bets. This is a role that other funders, such as governments or international development agencies, often are unwilling or unable to play given the uncertainty and risk inherent in innovation efforts.

- Implementing and scaling solutions that work | More than half of the big bet dollars went to implement and scale solutions that work. That’s not to say this type of work is devoid of innovation. Taking a solution that worked in one country and establishing it in another frequently entails adaptation to local context.

- Collaborating to finish the job | Ten percent of the big bet dollars fit this category, which frequently requires system change. Philanthropists often are well-positioned to coordinate such efforts, given their experience collaborating with such diverse stakeholders as governments, NGOs, and multilaterals. As we move closer to the 2030 deadline set by the UN to meet the SDG goals, we expect to see an increase in this category of big bets.

- Advocating for policy change | Advocacy efforts accounted for roughly 5 percent of big bet spending, an amount that belies the significant impact such spending can have. Bridgespan’s recent study of 15 successful social-change efforts highlighted the frequent need for advocacy.

Click on image to enlarge.

Click on image to enlarge.

Where Have Funders Made SDG-Aligned Big Bets?

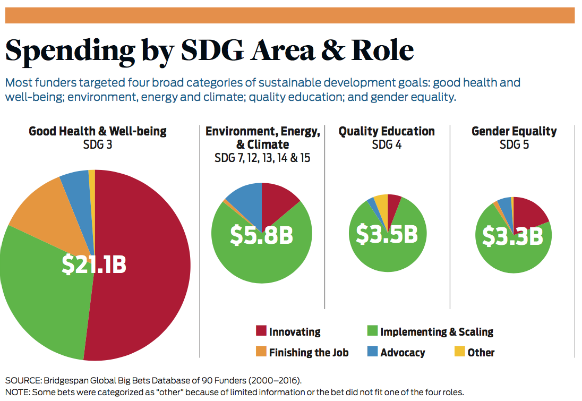

The $42.4 billion in big bets made between 2000 and 2016, however, flowed unevenly to the 17 SDGs. About half of the funding, $21.1 billion, went to a single SDG, number 3, Good Health & Well-Being. At the other end of the spectrum, seven of the goals, comprising roughly 40 percent of SDGs, collectively received $2.9 billion, just 7 percent of the big bet dollars.

Click on image to enlarge.

Click on image to enlarge.

Most funders targeted four broad categories of SDGs: health, education, gender equality, and environmental issues. A closer look at these four categories highlights the impact of big bets in service of innovation, implementation and scaling, finishing the job, and advocacy.

SDG 3: Good Health & Well-Being

Funding for SDG 3, Good Health & Well-Being, towered over all the other categories, attracting 364 big bets from 22 funders totaling $21.1 billion. The Gates Foundation dominated this category with 300 big bets exceeding $14 billion. But even after removing Gates funding, this SDG attracted the most money of any SDG. Eight of the 22 funders made big bets to support innovative solutions, such as new vaccines; nearly all made at least one big bet focused on scaling proven programs; and roughly one in four supported efforts to finish the job.

Wellcome Trust, a London-based biomedical research charity and one of the wealthiest foundations in the world, exemplifies funders that propel innovation. The trust supports more than 14,000 scientists and researchers in more than 70 countries. We identified 11 SDG-related health big bets by Wellcome since 2000, totaling $850 million. Of that, $320 million funded research to combat malaria, a major cause of sickness and death across the developing world. Wellcome’s funding contributed to the use of life-saving insecticide-treated bed nets and more than 50 other breakthroughs in malaria prevention and treatments. The fight against malaria has shown strong progress, with current malaria global incidence rates of 94 per 1,000 people at risk, a 41 percent decline since 2000.

“Our big bets, or long-term commitments, include funding on-the-ground research capabilities in Kenya, India, and Thailand,” says Dr. Michael Turner, head of infection and immunobiology at Wellcome. “We provide the stability needed for research progress. Our time horizon for investment payoff is more than 20 years.”

While Wellcome focuses on innovation, other health care funders focused more on partnerships to scale programs that work. The Children’s Investment Fund Foundation (CIFF), for example, partnered with the Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation and the Zimbabwe Ministry of Health and Child Care in 2010 to combat mother-to-child transmission of HIV. The three partners worked together to implement and scale World Health Organization recommendations in a country with one of the highest rates of mother-to-child transmission in the world.

CIFF committed approximately $45 million to the program between 2010 and 2015. “A big bet was the only way to tackle this issue,” says Kate Harrison, former program manager for CIFF’s Survive and Thrive program. When the program launched, the mother-to-child transmission rate in Zimbabwe was 28 percent. By 2015, it had fallen to 6.7 percent, saving an estimated 13,000 children’s lives. Nearly all (95 percent) of pregnant women in Zimbabwe now take advantage of these life-saving prevention services.

While global health receives the most philanthropic money, much still needs to be done to achieve all 13 sub-goals within this SDG, including ending the epidemics of malaria, TB, and neglected tropical diseases, such as river blindness; reducing by one-third premature mortality from noncommunicable diseases, such as cancer, diabetes, smoking related illnesses, and suicide; and halving the number of deaths and injuries from traffic accidents. A report by the UN’s Sustainable Development Solutions Network estimates an annual spending shortfall of $69 to $89 billion to reach the SDG’s ambitious health targets.

SDG 4: Quality Education

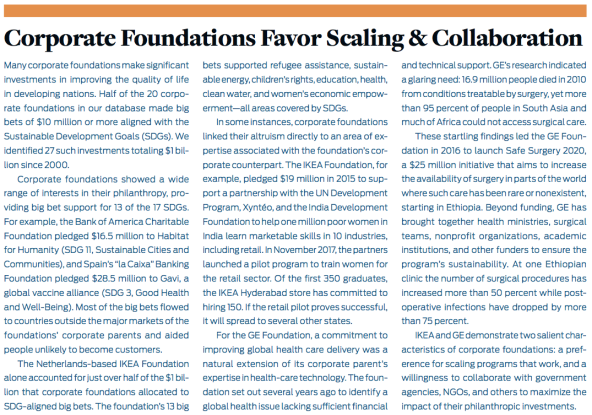

Nineteen funders in our sample invested $3.5 billion in 35 big bets targeting SDG 4, Quality Education. More than nine of every ten dollars went to implementing and scaling access to quality educational opportunities. Much of this work involved building public schools and universities, and investing in teachers and school leaders.

The Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN) illustrates the impact a major funder can have in

growing university-level educational opportunities. AKDN, led by His Highness the Aga Khan, the 49th hereditary Imam (Spiritual Leader) of the Shia Ismaili Muslims, has spent more than $1 billion since 2000 to construct and expand two AKDN universities. One of those universities is the University of Central Asia (UCA), which AKDN established in partnership with governments in Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, and the Kyrgyz Republic. UCA’s three campuses attract students from a region bisected by the historic Silk Road, a trade and transportation route that facilitated the global exchange of goods, cultures, and ideas for hundreds of years. This major initiative aims to nurture future leaders and spur economic development in Central Asia. “These institutions are critical for long-term sustainable development efforts in these countries,” says Khalil Shariff, CEO of the Aga Khan Foundation Canada.

In Africa and India, AKDN also has built the first three of 18 planned Aga Khan Academies, a network of schools for exceptional K-12 students in 14 countries. “These are leadership development engines for people who do not have the opportunity to access this quality of education,” says Shariff.

Similarly, Azim Premji, one of India’s most successful tech entrepreneurs, has committed billions of dollars over time to strengthening public education in India. “Education is perhaps the most organized social process and mechanism for developing a better society,” says Azim Premji Foundation CEO, Anurag Behar. “Good public education is also the foundation for a vibrant democracy.”

The Azim Premji Foundation has more than 1,500 employees focused on education in eight Indian states. The foundation partners with state public school systems for capacity building, and establishes field institutes at the district and state level for teacher education, leadership development, assessment reform, and curricular improvement. Behar recognizes that effecting the systemic education change Premji seeks will take multi-generational efforts and require “deep patience, unrelenting tenacity, humility, and capacity to work with the socio-political reality that is out there.” He reports heartening signs of progress, including visible changes in teacher capacity and practices.

The UN report estimates a yearly global education-funding gap of $39 billion through 2030. While significant progress has been made in expanding access to primary and secondary education in general, much remains to be done for targeted segments, such as girls and the disabled, and expanding access to other forms of education, including early childhood, vocational, and technical.

SDGs 7 and 12–15: Energy, Climate Change, and the Environment

Twenty-six funders made 75 SDG-aligned big bets on energy (SDG 7), the environment (SDGs 12, 14, and 15), and climate change (SDG 13) totaling $5.8 billion. Three out of four dollars went to scaling existing approaches to ameliorate these issues. Notably, a far greater share of the funding went to advocacy than in either health, education, or gender equality—14 percent versus roughly 3 percent for each of the other three areas.

Many of the big bets flowed through intermediaries such as the ClimateWorks Foundation, the Energy Foundation, and the European Climate Foundation, that receive and channel money to other organizations. Funders are in essence outsourcing the process of developing strategies, searching for worthy grantees, structuring the deal, and tracking metrics that measure progress. These intermediaries give foundations and individuals an effective way to implement and scale programs that require more technical expertise than is available in-house.

ClimateWorks, for example, attracted major gifts from the David and Lucile Packard Foundation and the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, which made multiyear gifts of $850 million and $611 million, respectively. ClimateWorks makes grants to six philanthropic investment portfolios supporting organizations and initiatives around the world that are working to solve the climate crisis. It also devotes considerable resources to help businesses, governments, and communities implement energy-efficient technologies.

Funders outside the United States also backed climate change initiatives. Among them, the Geneva-based Oak Foundation made a $75 million gift over five years to ClimateWorks. “We are a family-led foundation, and our trustees think big and have made major investments in a broad variety of areas,” says Kathleen Cravero, president of Oak Foundation. “But our $75 million ClimateWorks grant is our largest grant yet. There is a lot of energy around doing something significant in the area of climate change because it’s such a pressing global issue. We are doing more thinking around big bets going forward, assessing where they can significantly drive change.”

To date, SDGs with energy, climate change, and environmental objectives have made modest headway. For example, from 2012 to 2014, renewable energy increased from 17.9 to 18.3 percent of total energy consumed worldwide. And global energy consumption growth slowed to a 1 percent increase between 2015 and 2016, due largely to efficiency improvements. But overall progress in these SDG areas falls far short of what is needed to reach 2030 goals.

The UN did not calculate a figure for annual increases in energy, climate change, and environment expenditures to meet the 2030 goals. A shortage of data made it impossible “to determine by how much current public and private expenditures need to increase in response to climate change adaptation and mitigation,” the report noted.

SDG 5: Gender Equality

A dozen funders in our database made 82 big bets in gender equality totaling nearly $3.3 billion since 2000. The Gates Foundation accounted for almost half of all grants—$1.4 billion. Eight of every 10 dollars went to implementing and scaling effective programs; one in 10 funded innovation.

Among big bet funders committed to gender equality, the Susan Thompson Buffett Foundation (STBF) stands out for its commitment. Backed by Berkshire Hathaway CEO Warren Buffett and named after his late wife, STBF is the largest private funder of sexual and reproductive health and women’s rights worldwide. Since 2004, it has made 19 separate big bet investments in organizations supporting gender equality, primarily in implementing and scaling programs addressing sexual and reproductive health.

For example, the foundation provided DKT International with a multiyear gift of $118 million. In 2015 alone, DKT reported serving 30 million couples and preventing more than 5 million unwanted pregnancies, 13,000 maternal deaths, and 2.6 million abortions.

STBF has also given more than $300 million since 2011 to Population Services International (PSI), which works in more than 50 countries in the areas of malaria, family planning, HIV, diarrhea, pneumonia, and sanitation. In 2015, PSI reported that it saved the lives of 9,246 mothers, prevented nearly 4 million unintended pregnancies, stopped more than 234,000 new HIV infections, and avoided an estimated 379,286 deaths due to diseases like malaria, diarrhea, and pneumonia.

The Ford Foundation, long known for its commitment to reducing poverty and injustice, has also dedicated significant resources to gender equality. In 2012, the foundation announced a five-year, $25 million commitment to help end child marriage. Ford’s funding supported advocacy work at global, regional, and national levels and linked that work with policy dialogues; community-based, multi-stakeholder research into what works; and culture change efforts, among other things. One of the main conduits for these efforts was Girls Not Brides, a global partnership spearheaded by The Elders (an independent group of global leaders working together for peace and human rights). Girls Not Brides now brings together more than 900 civil society organizations committed to ending child marriage and enabling girls to fulfill their potential.

Trend data suggests such broad, collaborative efforts may be helping to produce results. Child marriage is declining. One in three women married before age 18 in 2000, but that number was cut to one in five in 2018. Ford’s support for advocacy has helped to sharpen understanding of the problem and set milestones to measure progress. Of course, the ultimate solution is complex and cultural, and will require the collective championing of many, including governments in the countries where child marriage is most prevalent.

Concerted public and private efforts since 2000 to improve the social and economic status of women and girls has made a difference. Girls’ access to education has improved and progress has been made in the area of sexual and reproductive health and reproductive rights, including fewer maternal deaths. Nevertheless, gender equality remains a persistent challenge for countries worldwide, and the lack of equality is a major obstacle to sustainable development.

The UN sidestepped putting a price tag on the annual gap in gender equality funding because “the bulk of investment needs … must be included in gender-sensitive sector investments, including education, health, and access to basic infrastructure services.” A 2006 analysis, however, considered this complexity and concluded that donors should commit an additional $13 billion annually to gender equality.

Moving the SDGs to the Foreground

The clock is ticking on fulfilling the SDG agenda by 2030. The UN’s 2017 Sustainable Development Goals Report summed up the challenge: “Focused actions are needed to lift the 767 million people who still live on less than 1.90 US dollars a day, and to ensure food security for the 793 million people who routinely confront hunger. We need to double the rate at which we are reducing maternal deaths. We need more determined progress towards sustainable energy, and greater investments in sustainable infrastructure. And we need to bring quality education within reach of all….”

UN Secretary-General António Guterres worries that the SDGs are off to a slow start. “If the world is to eradicate poverty, address climate change, and build peaceful, inclusive societies for all by 2030, key stakeholders… must drive implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals at a faster rate,” he said upon release of the Sustainable Development Goals Report 2017 update report.

Momentum clearly is building. More than 50 governments have integrated the SDGs into their development plans. Businesses also are discovering how sustainable business models can create economic opportunities. For instance, the Rise Fund, a $2 billion impact investment offshoot of global private equity firm TPG, factors SDGs into its investment decisions. Unilever’s CEO Paul Polman helped found the Business & Sustainable Development Commission, which champions business opportunities tied to the SDGs. And companies ranging from Mars to Coca-Cola have publicly acknowledged the value they see in the SDGs.

“Corporations have really jumped on the SDGs,” says the UN Foundation’s Calvin. “Everyone, including the philanthropic community, has a huge role to play and can do more to make a larger impact,” she adds. “Unless the level of ambition and collaboration increases, there’s no way we’ll meet the targets.”

The recent burst of new large-scale efforts to aggregate philanthropic capital hold promise here. A number of funders have joined ambitious collaborations purpose-built to deploy big bets in SDG areas. Co-Impact, a new collaborative involving donors from across the globe, plans to invest $500 million in grants of up to $50 million each in health, education, and economic opportunity for underserved populations across the developing world. The Audacious Project (a new funder collaboration housed at TED, the nonprofit devoted to “ideas worth spreading”) has raised more than $400 million to fund ideas that have the potential to impact millions of lives. The Reaching the Last Mile Fund, launched in November 2017 by the Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and hosted by the END Fund, aims to raise $100 million to finance work towards eliminating river blindness and lymphatic filariasis.

More broadly, the Foundation Center reports that since January 2016 foundations have contributed $53 billion in grants aligned with the SDGs. While encouraging, the figure “is not meant to suggest that foundations intentionally aligned all that giving with the SDGs and/or internalized the SDG framework,” according to the Foundation Center. “It’s easy to articulate your work within the SDG frame,” says the UN Foundation’s Calvin. “But shifting to a much more active role in the collective work required to implement and deliver on the SDGs is what is needed. Aligning with the SDG framework while otherwise remaining business as usual will fail to make the significant changes needed. Let’s hope that the next phase of this chapter brings about more focus on measuring impact and trajectories for SDG progress and partnerships.”

Any funder seeking to learn more about moving the SDGs to the foreground of their grantmaking can turn to several sources for help. The SDGfunders.org website offers an Indicator Wizard that helps philanthropists determine which SDGs relate to their work and which indicators to track to measure impact. The SDG Philanthropy Platform facilitates partnerships between foundations, governments, and the private sector. The UN has established the Sustainable Development Solutions Network to mobilize global scientific and technological expertise to promote practical solutions for sustainable development. And the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development has launched the Global Network of Foundations Working for Development to serve as a bridge between foundations and policy makers.

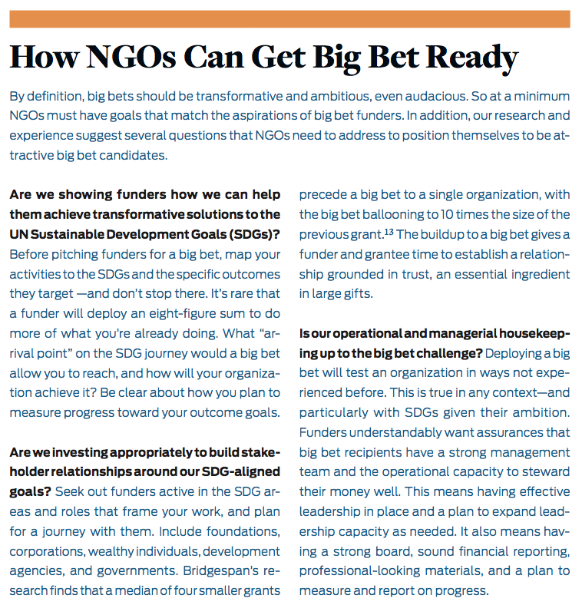

For funders ready to embrace the SDGs, answering these three questions can also help:

Can you describe how your grantmaking aligns with the SDGs and the appropriate development targets? Start by matching your grant portfolio with the 17 development goals. The full value of the SDGs as a common global development language cannot be reached until funders understand how their work aligns with the UN’s 2030 goals, apply that framing to their grantmaking, and take part in the collective work required to implement and deliver on them. Make sure you can describe your outcome target, the more audacious the better, and exactly how you will get there.

What role(s) can best advance your philanthropic goals? Most of the big bet grants we identified went to implementing and scaling successful programs or services, an unsurprising finding given the need to expand programs that work. But our research identified three more roles funders typically play to deliver social change: developing and testing innovative solutions, collaborating to finish the job, and advocating for policy change. Be clear about which of these roles best matches your own goals. While our data indicate that funders often gravitate to a single role, that role also may change over time as a funder’s goals change.

How should you engage with others doing this work? The SDGs lay out sustainable development goals that no single actor—government, business, NGO, or funder—can accomplish alone. Partnerships and collaborations offer funders a way to leverage both their financial resources and advisory expertise, as demonstrated by many of the funders in our study. This isn’t to say that independent efforts aren’t a viable option. Some funders may prefer the solo approach to preserve their autonomy and avoid some of the costs of collaboration (such as the extra time and energy spent on alignment with collaborators). Even so, knowledge of what others are doing in your areas of interest can and should inform your work. The SDG framework makes it easier to identify others from whom you can learn and work alongside.

Click on image to enlarge.

Click on image to enlarge.

The world has never before aspired to achieve goals as ambitious and costly as the SDGs. If past is prologue, global philanthropy is prepared to invest tens of billions of dollars—often in the form of big bets—to make strides toward ending poverty, protecting the planet, and ensuring health and prosperity for all by 2030. While the journey has just begun, the international philanthropists we studied seem eager to bring their enormous resources to bear on these goals. More than ever, the world needs donors willing to think big, innovate, take risks, and build collaborations.

Methodology for Compiling Big Bets

We used US and international public sources, such as Forbes’ “America’s Top 50 Givers” and the Charities Aid Foundation’s World Giving Index, to identify three types of donors and rank them by size: traditional foundations, corporate foundations, and wealthy individuals. In the United States, we identified 30 traditional foundations (independent, community, and family), 10 corporate foundations, and 10 individuals. Internationally, we identified 20 foundations, 10 corporate foundations, and 10 individuals.

We selected $10 million as the threshold for a big bet because it is low enough to capture major gifts in fields where organizations and initiatives tend to be smaller, yet high enough that gifts would have the potential to fuel significant change. We did our best to consolidate multiple grants from a single donor for the same initiative into one big bet, even if the grants occurred in multiple years and independently would not meet the $10 million threshold. We also conducted interviews with representatives of several international foundations to gather information on big bet activity not available publicly. Given our focus on the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals, we excluded gifts to arts institutions, religious causes, disaster relief, and patient assistance programs. We also excluded gifts for medical or higher education institutions in high-income countries, unless funders stipulated the gift for antipoverty initiatives or underfunded diseases that disproportionately affect low-income people. But we included such gifts in low- and middle-income countries.

We strived to create the most comprehensive database possible based on available data, and we believe we have captured a majority of big bets our sample of donors made in this period. Still, we have likely missed some. Though foundations in the United States must report all grantmaking activity, individuals and many foundations based abroad are not subject to the same requirements. We relied on publicly available information for the bulk of our research and supplemented this with interviews whenever possible.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Kim Ogden, Roger Thompson & Sridhar Prasad.