Problem Solved: A Powerful System for Making Complex Decisions With Confidence and Conviction

Cheryl Einhorn

240 pages, Career Press, 2017

Leaders in the social sector running local, national, or global organizations encounter daily challenges in delivering work related to their mission. At the same time, they face a range of other complex questions, such as how to adapt a program model to meet changing needs, how to diversify revenue to become more sustainable, or what path to scale to pursue in order to reach more people. While those kinds of questions are difficult on their own, these leaders also operate in a diverse environment of stakeholders including team and board members, the beneficiaries of the organization’s work, policymakers, and public officials. An organization may have a well-defined process for strategic planning or feasibility assessment, but there is often a need for a holistic and systematic way to make big decisions better. That’s what the AREA Method offers.—Cheryl Einhorn

John Christopher, the founder of the nonprofit Oda Foundation, which provides basic healthcare services to people in the rural village of Oda, Nepal, had been thinking about how to expand his nonprofit’s impact when an earthquake struck Nepal in 2015. Since John’s organization was already fully operational and on the ground, he and his organization had an unexpected opportunity to become a go-to organization for aid groups wanting to come into Nepal in the wake of the disastrous earthquake.

At the time of the earthquake, Oda’s health clinic was serving about 1,000 patients a month, addressing a broad range of health problems including acute respiratory infections, typhoid fever, and trauma from common accidents and injuries. Oda was also conducting small education seminars, such as one focused on keeping teenage girls in school by providing education about, and hygiene products for, menstruation. John had quickly seen that his foundation could make a real difference. Since opening its doors on December 12, 2013, Oda has served about 25,000 of the addressable area’s approximately 50,000 residents and the number of easily preventable deaths dropped to zero in 2014, from 50 in 2013. The menstrual hygiene education campaign had reduced school absences in the village by about 70 percent.

But what was the best way to transform his on-the-ground clinic into a more useful health service provider for Nepal? How could he best serve the health needs of a country that suddenly looked very different from the country where he’d operated for the past two years?

He laid out three different paths he might follow. Path One: expand beyond his rural clinic by opening a new health clinic on a main road where his staff could easily service more patients. Path Two: accept the Nepalese government’s offer to partner with their existing health clinics to expand the government’s treatment and care. Path Three: in a country with such treacherous terrain, invest in drones to drop and deliver medical kits to more remote areas that had little or no access to healthcare facilities.

John was stumped. Which option should he choose? The strategies were very different from one another. How could he decide which course of action was the right one? He didn’t want to rush to judgment, even though time was of the essence. How could he swiftly arrive at a well-reasoned and researched outcome to make an educated decision for a future that at first glance seemed so unpredictable?

John was faced with a high-stakes decision: a decision that would have a long-term impact on the well-being of his foundation and its reputation, a decision that needed to be made with incomplete information amid a volatile backdrop, in a changing environment with an urgent need for medical care.

That’s the problem that John came to me with just after the earthquake. We had met just days before the earthquake, in the halls at Columbia University’s Business School, where I was co-teaching a course in Advanced Investment Research. For this course, I was modeling and teaching a research and decision-making system that I’d developed, and which I call the AREA Method. I realized AREA was applicable to John’s decision and agreed to help him think it through.

As a journalist, teacher, consultant, mother, sister, wife, daughter, and friend, I’ve learned that there are few absolutes—and many gray areas. We each experience the world differently, bringing our own viewpoint— and biases—to everything we do. That’s why I put together the AREA Method: as a way to navigate gray areas and avoid those mental shortcuts that enable us to make small decisions easily but may impair our judgment when making big decisions. In short, I was searching for a way to make big decisions better.

But in developing AREA, I realized that the process does much more than provide a research and decision-making roadmap. It makes your work work for you. It heightens your awareness of the motivations and incentives of others. It helps you to avoid bias in your work and to engage with people and problems more mindfully. For while decision making is about ideas, ideas aren’t enough; there is an important gap between having ideas and making good decisions about what to do with those ideas.

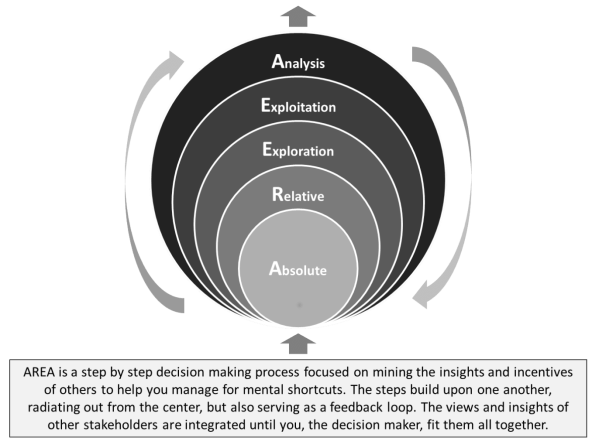

The AREA process gets its name from the perspectives that it addresses: absolute, relative, exploration & exploitation and analysis. The first A, or Absolute, refers to primary, uninfluenced information from the source, or sources, at the center of your research and decision making process. R, or relative, refers to the perspectives of outsiders around your research subject. It is secondary information, or information that has been filtered through sources connected to your subject. E, or exploration and exploitation, are the twin engines of creativity, one being about expanding your research breadth and the other about depth. Exploration asks you to listen to other peoples’ perspectives by developing sources and interviewing. Exploitation asks you to focus inward, on you as the decision maker, to examine how you process information, examining and challenging your own assumptions and judgment. The second A, analysis, synthesizes all of these perspectives, processing and interpreting the information you’ve collected.

By emphasizing perspective-taking, AREA acknowledges that although you may think that you understand how to solve a particular problem, your understanding of that problem is most likely incomplete and different from how other key actors see it. By walking in their shoes, you will better recognize their considerations and incentives. You may even come to understand the facts differently. Further, by moving through a research and decision making process that acknowledges the need for empathy and understanding, you can also better manage your own perspective, assumptions and judgments and more easily make a thoughtful and successful decision.

In addition, AREA inverts traditional decision making. It begins with framing your decision not as a problem per se, but instead asking you something that you can often much more easily define: What constitutes a good outcome for you personally? It turns decision making upside down so that instead of focusing on what you don’t know, you can focus on what matters to you in the outcome.

By defining what matters, what I call your “critical concepts,” AREA gets at what you are really solving for. The critical concepts not only get at the driving purpose behind your decision but also they keep your work targeted and focused on the few key factors that you really need to understand.

Initially, John had one overarching critical concept, which was to help more Nepalese people—quickly. But which expansion plan was best?

He began gathering absolute data, information directly from the target of his decision. In this case it was information from the Nepalese government about healthcare and population data. This process clarified his critical concepts so that by the end of the first stage of research, “I had five critical concepts,” says John. “I needed to understand whether each option had government support as well as community support. I needed to know what costs were involved, and what impact the option would have on healthcare in our remote Kalikot region. And I needed to figure out whether each option fit with our core competencies. Was it something we were good at and we had had success with?”

For his relative and exploration research, John conducted a literature review, completed an industry mapping exercise and interviewed other nonprofits that worked in emerging nations after a natural disaster, or specialized in healthcare, or knew or had familiarity with Nepal’s government. He ruled out the drone delivery kit option, as both the technology and infrastructure necessary weren’t available in Nepal.

This narrowed John’s expansion options down to two: to open a second clinic, or to partner with the government in providing medical care and/or education. John’s research also helped him to narrow his CC’s down to three. First, did Oda have buy-in from both the government and the community for both options? It was not sufficient to only have buy-in from one of his two constituencies. Second, did Oda have the operational capacity to succeed in both options? And third, was each option financially prudent? Would he be using Oda’s money in the best way possible?

Throughout his research process, John kept finding data that suggested that partnering with the government would be a mistake. He learned that the government’s clinics had a poor reputation. Yet, by following the AREA method, John was able to fully understand the risks associated both with opening a second clinic and with working with the government. The risks were of different magnitude and, it turned out, one set could be more easily addressed than the other.

Opening a second clinic seemed to best draw on Oda’s core competencies. However, John’s exploitation work, a series of exercises exploring his assumptions alongside his evidence, revealed something quite unexpected: opening a second clinic was the option that had a strong likelihood of bankrupting the organization. Not only did it require hefty upfront capital costs to fix and retrofit the building, but there was also no good way to limit patient flow and therefore to ensure that the patient traffic wouldn’t exceed Oda’s ability to cover the costs of treatment. While this option met John’s first Critical Concept (government support), it did not meet his second relating to quality care, or his third CC related to financial efficacy. It was a no-go.

Yet recognizing the risks of opening a second clinic allowed John to use his final phase of AREA, analysis, to focus on solvability. Could he find a way to work with the government, yet work around the government’s poor healthcare reputation?

AREA Analysis guided him through a pre-mortem, an exercise that improves decision making by imagining that your decision has failed, then investigating how and why it did so and then constructing a plan to prevent that failure. The exercise helped John realize that by designing an education campaign, Oda could maintain its independence and replicate the previously successful education campaign that kept girls in school during their monthly menstrual cycle. This gave John confidence and certainty that his decision could succeed. He ultimately realized that partnering with the government met all of his critical concepts: It was his best option.

By following the AREA Method, John not only came to an unexpected decision to partner with the government, but was also more clearly able to articulate his goals for Oda, as well as his process, and this led to greater donor buy-in. So by the time John completed his AREA research, current and new donors had covered the full cost of the project.

Ultimately, by using data supported by AREA, the Oda Foundation raised close to $200,000 in cash and in-kind donations through the first 8 months of 2015, more than doubling his 2014 fundraising total. In other words, by the time John made the decision to partner with the government he’d already fully funded the plan.

He’d identified new potential donors and was able to reach out to them as part of his Exploration work. “They were taken with our mission and with the depth of my focus, with my research and due-diligence,” says John. “It enabled me to raise more money than I’ve ever raised before—and more quickly.”

Not every AREA research project will have such a “happy ending,” but by following the AREA Method, I believe that you too will be able to better articulate your goals and your path to success. By making thoughtful, confident decisions anchored in research, you will be able to articulate the “what” the “why” and the “how” of your decision in ways that resonate with others. You will have written out the thinking behind your decision and your picture of success in a vivid, compelling way.

At its heart, the AREA process of perspective-taking uniquely combines the social performance side of human behavior with the metric and evaluation aspects of decision making so that you solve problems holistically. It’s meant to help you check your ego, enable you to better judge the incentives of others, and explore a situation more objectively. In so doing, it builds both self-awareness and empathy. As AREA becomes second nature it can be part of the frame you bring to the world around you. As a result, it may allow you to live your life more mindfully and deliberately. With the right framework, the right approach to decision-making—the right process—you can turn good ideas into great thinking.