(Photo by Unsplash/Mika Baumeister)

(Photo by Unsplash/Mika Baumeister)

The past several years have seen dramatic growth in social movements demonstrating their dissent through public mass mobilization and acts of civil disobedience, from Black Lives Matter and Fridays for Future to the massive protests by Indian farmers. According to one study, the number of protest movements tripled from 2006 to 2020. But despite this meteoric rise in popularity, protest movements often claim that they are underfunded, under-resourced, and ignored by philanthropists.

They are right. Throughout history, protest movements have been the instigators of several instances of large-scale social change, and they deserve greater funding to continue. Funders should direct a greater proportion of their resources towards protest movements, to build a stronger ecology of social change. Given how even woefully underfunded protest movements have had catalytic impacts in bringing about large-scale positive change, supporting young, upcoming protest movements might be one of the most impactful things philanthropists can do.

How Much Funding Do Protest Movements Get?

Protest movements often don’t have official legal structures, formal leadership teams, or governance policies, which can make it hard to identify what we are talking about. For the purposes of this article, we can consider protest movements to be social movements—an informal collective of people pursuing a shared social goal—who utilize protest as one of their main tactics in bringing about their intended social change (though not to say that protest is their only tactic). Common examples of such protest movements could be Black Lives Matter, Occupy Wall Street, or the Suffragettes in the 1900s “Votes for Women” movement.

Are you enjoying this article? Read more like this, plus SSIR's full archive of content, when you subscribe.

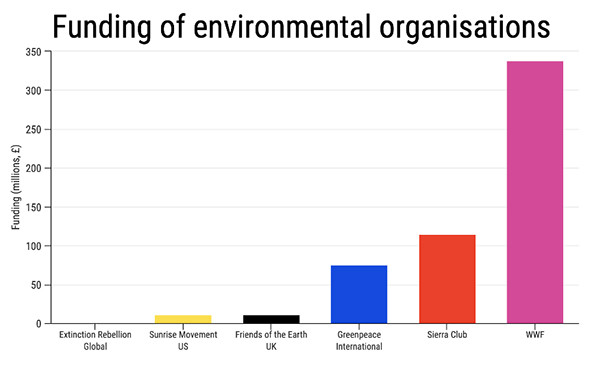

To examine the claim that protest movements deserve greater funding, we can compare the funding allocated to protest movements versus charities and NGOs working on similar issues. For example, consider Extinction Rebellion (XR), one of the most well-known climate movements over the past several years: The figures shared by XR Global puts their annual income around £750,000, based on the 2019 and 2020 figures. In comparison, Greenpeace International puts its annual income for the same period at about £75 million, roughly a hundred times larger. The Sunrise Movement in the US draws in much more funding than XR, but is still dwarfed by large environmental charities such as the World Wildlife Fund (WWF). The graph below highlights the asymmetry in funding for protest movements relative to NGOs.

While these numbers are inexact, and vary depending on the organisations being compared, the size of the disparity is clear: even the most successful and popular protest movements, receive dramatically less funding relative to established popular charities working on similar issues.

How Effective Are Protest Movements?

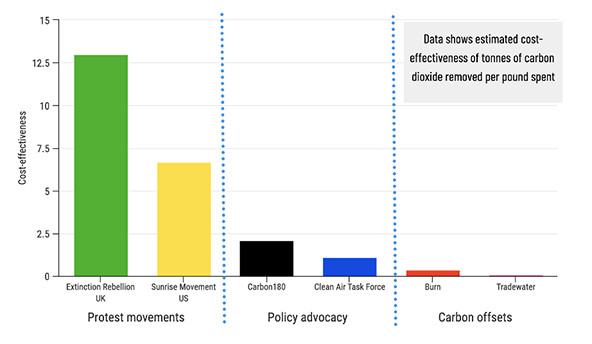

If our concern is doing as much good as possible with our limited resources, then the question to ask of climate-focused movements is how much carbon they avert from the atmosphere per dollar they spend. In the case of animal justice-focused movements, it might be the number of animals spared years of suffering in factory farms. And so on: If we care about creating a better world as effectively as possible—not just giving away money—the real question is how effective are these protest movements in bringing about positive social change?

As part of research conducted at Social Change Lab, a nonprofit dedicated to better understanding the impact of social movements, we’ve conducted cost-effectiveness analyses on Extinction Rebellion and the impact they had on reducing carbon emissions. These analyses aren’t conclusive, and although more research is being done to refine them, the calculations often involve subjective assumptions, such as the exact role a certain organisation played in a policy change.The research was conducted by examining the recent changes in climate policy in the US and the UK, the impact of these policies on carbon emissions and the contribution that XR or the Sunrise Movement made towards causing this policy change.

According to our calculations, Extinction Rebellion UK’s work averted 13 tons of carbon dioxide per £ they spent on advocacy; when Giving Green, a climate charity evaluator, conducted similar calculations for the Sunrise Movement, they found that per dollar spent by the Sunrise Movement, they averted approximately five tons of carbon dioxide being pumped into the atmosphere. But while these numbers sound impressive, it’s crucial to compare them to other climate organisations, to get a clearer understanding of the effectiveness of these protest movements. The cost-effectiveness of XR and the Sunrise Movement perform better than one of the top-rated climate charities globally, Clean Air Task Force, by factors of 12x and 6x respectively.

The Impacts of Protest Movements

How do these protest movements have such big impacts? You might wonder how thousands of people on the streets can lead to a reduction in carbon emissions, as the links aren’t always clear. There can be several mechanisms through which protest can spur social change, namely: changing public opinion, shifting public discourse, influencing policy, and affecting voting behavior.

Public opinion: Research by Dr Ben Kenward from Oxford Brookes University shows that public concern for the climate increased in the UK after a period of mass protest by Extinction Rebellion, which confirms the findings of polling by YouGov, a research and polling organisation. Crucial research compiled by the Ayni Institute finds that major 1950 and 1960s civil rights protests, led by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., were highly correlated with significant increases in concern for racism in the US.

Public discourse: Protests can directly influence the way media, politicians, or the public frames or talks about certain issues. Omar Wasow, an assistant professor of politics, found that civil rights protests in the 1960s was effective at “agenda seeding,” causing an increase in media coverage of civil rights and an increase in the frequency of mentions in Congressional speeches. More recent research, by sociologists at Indiana University, found that the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement increased online searches for key themes of BLM—such as systemic racism and prison abolition—by over a hundred times during the protests. Indeed, attention towards these ideas remained high even six months after the end of the George Floyd protests, with social media attention to “systemic racism” still 5.5x higher than the previous year.

Influence on policy: A study of Belgian elected representatives found that exposure to protests on asylum issues affected the beliefs of policymakers, which in turn could affect their positions on various legislation. Even more concretely, a Serbian mining project was scrapped after national mobilisations protested the environmental damages of the project, and BLM protests spurred legislative changes across the US, as well as a 15-20 percent reduction in police violence.

Influence on voting behavior: Wasow, in the same study from above, found that US counties close to nonviolent protests saw presidential Democratic vote share among whites increase 1.3-1.6 percent, whilst violent protests caused a 1.6-7.9 percent shift among whites towards Republicans.

How Do We Know Which Movements to Fund?

Beyond climate and anti-racism, protest movements have had vast positive impacts in a range of other pressing issues: Mass farmer protests in India against controversial agricultural reforms led to the government backing down after over a year of sustained protest. The newest President of Chile has plans to address inequalities within the country, partially owing to himself being a former student leader of recent Chilean protests against corruption and inequity. The Indian Independence movement, led by Mahatma Gandhi, led to the ending of British rule in India.

Given the growing body of evidence that protest movements can be a highly effective way to create positive social change, what should philanthropists and advocates do about this? Devoting a greater proportion of available resources seems clearly beneficial, since additional resources could have the ability to propel these movements to even greater heights: mobilising more people, shifting public opinion, changing dominant narratives, and influencing key policy. But since resources are limited, and we want to direct them towards the movements and organisations that will have the greatest positive impact, the question of choosing which protest movements to support must be addressed.

Given that movements are unpredictable, it can be hard to know which ones have the highest chances of success. Below, I outline various factors that philanthropists and advocates should look for in protest movements when deciding whether to support them.

1. Clear Purpose and Shared Values

It’s not enough to simply point out the shortcomings of our current system without proposing an alternative. One example of this could be the Occupy movement of 2011, in which people in hundreds of cities globally occupied financial districts to protest rising inequality and corrupt institutions. Despite the successes of Occupy in building concern around wealth inequality, one of its shortcomings was the lack of ability to present a succinct vision for a better future. This, ultimately, led to fractures within the movement and people leaving due to a lack of clarity in their aims, and how to achieve them. By comparison, the 1960s Civil Rights movement trained activists for months, thanks to the help of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, with the focused aim of desegregating lunch counters, first within Greensboro then much more broadly across the United States. These activists not only had a clear objective to steer their work, but also a strong shared set of values and principles, another vital component to ensure the longevity and stability of protest movements.

2. Strategic Theory of Change

Once a movement has shared goals and principles, the next step is a theory of change for how they will bring about their vision. Some movements have a tactic they like (such as blocking roads or going on strike) which they use without considering how it fits into their wider strategy. Effective movements should define their vision and set a strategy based on it, using a method such as a SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats) analysis. A promising movement is one that has a clearly articulated theory of change, with the necessary campaigns, strategies and tactics outlined that will help them achieve their goals.

3. Clear Governance and Processes

As anyone who has been involved in a grassroots movement might know, there are always challenges around membership, compensation, and decision-making. These topics can tear groups apart, leading to some of the best people leaving, or otherwise spending a significant proportion of time on internal politics rather than tackling the issue at hand. A promising protest movement recognises these risks and mitigates them by having clear governance and processes around thorny issues. Specifically, clear and agreed policies around decision-making, compensation of activists, harmful behaviors and people being asked to leave the movement are crucial to ensuring long-term health and success. A study on protest group success also concludes that the level of organisation of protest movements is one of the key factors in predicting success.

4. Ambitions to Scale, With the Planning to Make It Happen

Erica Chenoweth found that no movement that galvanised over 3.5 percent of the population in active participation failed to achieve its aims. Therefore, protest movements must have huge ambitions to scale, with the required meticulous planning. For example, Extinction Rebellion was faced with a dilemma when organising their first “Rebellion” in April 2019. Does this new group just occupy one site in Central London for two weeks, already a crazy feat, or do they aim for more? With little indication of how many people were coming, and based mostly on hope, XR decided to occupy five sites in central London, hoping that people would rise to the challenge—and they did. Thousands of people came down, many of whom got arrested, which ultimately led to the UK government declaring a climate emergency and an exponential growth of XR both in the UK and globally.

However, none of this would be possible without the effective planning required to make these moments of the whirlwind happen. Specifically, movements should have clear plans for how to roll out trainings nationwide, such as the five-day training programs delivered by Otpor!, on how to skill up and integrate new activists. Nonviolent trainings are the bread and butter of protest movements, used by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee in the 1960s Civil Rights Movement, Extinction Rebellion, the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, and beyond. In addition, the movement should have plans to scale its recruitment, onboarding, fundraising, finance, and outreach. The key question movement leaders should ask when designing processes and infrastructure is: Will this work if 100 new people join? How about 1,000? And how about 10,000?

5. Diversity and Unity

Research shows that the public and politicians are much more likely to be swayed by protests that attract a broad range of participants and organisations. In addition, the same research finds that unity in the message of the protestors, such that they have a clear and shared message, can be highly influential in positively affecting public and policymaker opinion. Therefore, funders should seek to support protest movements that are attracting a diverse set of participants, building alliances across society, and producing a cohesive and unified external message.

How Can Funders Support These Movements?

Some of these requirements might seem to be a tall order for many up-and-coming movements, often made up of people working in their spare hours for little to no money. But many of these characteristics can be identified early on, especially the elements of a shared purpose, ambitions to scale, and a strategic theory of change. Moreover, funders can support potential impactful protest movements in developing their thinking early on by funding their frontloading, the time where leaders design the strategy, structure, story, and culture of the protest movement. This is a crucial time when the core team can work closely together to build their vision, and the steps required to execute it successfully. This strategic planning was used successfully in the Indian Independence Movement, the Civil Rights Movement, as well as the Sunrise Movement in the US.

Funders can also choose to fund grassroots movements through existing umbrella or funding entities that deliver grants to these groups. Thousand Currents, Climate Emergency Fund, and Movement For Black Lives are just some examples of organisations that deliver funds to activists and groups organising on the frontline of issues, across women’s rights, indigenous rights, climate action, anti-racism, and more.

In addition, supporting movement-building infrastructure is another key, and less risky, way funders can contribute towards the capacity building of protest movements. Organizations such as Momentum Community, Ayni Institute, Future Matters Project, Climate 2025, and NEON all support various movements for social, climate, or racial justice, by providing resources such as training, incubation programs, mentoring, and fiscal hosting.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by James Ozden.