Do funders use knowledge to inform and improve their work? If so, how do they use it? What role(s) does it play?

These were some of the questions we asked four years ago when we started working at the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation and inherited a longstanding strategy called “Knowledge for Better Philanthropy.” Through this strategy, we fund the independent creation and dissemination of knowledge about the practice of philanthropy, with the goal of informing and improving funders’ work. These grants support publications like SSIR and the Nonprofit Quarterly, as well as organizations such as The Bridgespan Group, FSG, the Center for Effective Philanthropy, Grantmakers for Effective Organizations, the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy, and The Philanthropy Roundtable.

The organizations we fund generally understand the “reach” of their knowledge products—the number of website visitors, report downloads, and email subscribers they have. But they, like us, find that measuring their influence on philanthropic practice is a tougher task. Moreover, each has historically “gone it alone” in their audience research; they have been able to analyze their individual slice of the market but know less about the bigger picture. Together, we decided it was time for a different approach.

We selected two firms, Harder+Company and Edge Research, to conduct a first-of-its kind collaborative field scan aimed at understanding how knowledge products influence philanthropic practice. The field scan included a survey with 738 foundation staff respondents, 75 interviews with a representative sample of foundation staff and board members, and four in-depth case studies. The survey was unique because 11 of the sector’s major knowledge producers and disseminators collaborated to provide their foundation audience data to the survey respondent pool. Of course, this audience research was conducted in-line with all of the participating organizations’ audience/user privacy policies, and to help each organization better understand both its audience and the broader market.

Are you enjoying this article? Read more like this, plus SSIR's full archive of content, when you subscribe.

Here are some highlights and lessons from our research:

Funders do use knowledge.

Importantly, we found that knowledge does indeed influence funders’ practice. Funders primarily use it to question or affirm current practice, and to compare their foundation to the field.

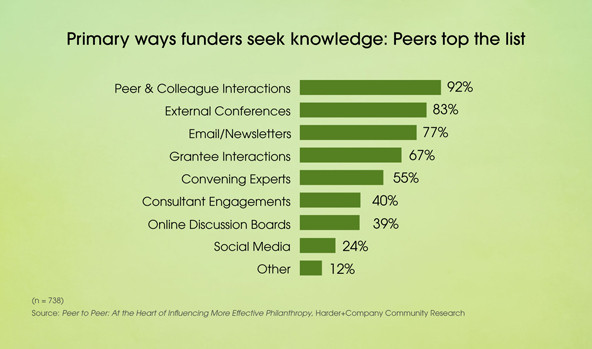

Peers are the main way funders seek out knowledge.

Funders’ primary source for knowledge is peers and colleagues (92 percent), followed by conferences, email/newsletters, and grantee interactions. It is crucial for knowledge producers to understand that peers and colleagues play a central role in information sharing, because it means research findings are likely filtered and interpreted as they move from peer to peer. Over time, this could lead to the misinterpretation of research or shifts in emphasis. Knowledge producers and disseminators should also keep in mind that people may actually use and cite something in their work without necessarily reading the original source material(s).

Curation is important.

One challenge facing knowledge producers is that foundation staff feel overwhelmed by the volume of information coming at them, regardless of whether or not they “opted-in” to receive it. Similarly, foundation boards say they face their own firehose of information and generally look to staff to curate knowledge about philanthropic practice; it rarely reaches them directly.

This firehose of information may in part drive the popularity of industry conferences. In-person gatherings create the space for learning and sharing with colleagues, away from the daily grind of overflowing in-boxes. They also enable attendees to pick and choose the topics most relevant to their work from a menu of content.

Here are some ways knowledge producers and disseminators can help break through the firehose of information:

Grantees are an important source of knowledge.

More than two-thirds of survey respondents (67 percent) cited grantee interactions as one of the main ways they seek out knowledge. This finding stood out to us because while power dynamics between funders and grantees may sometimes inhibit candor, it’s clear that many funders recognize grantees’ valuable expertise. Nonprofit leaders have the ears of their funders, and can influence a funder’s thinking and decision-making. We hope this finding gives grantees’ more confidence to use their funder relationship not only as a financial connection, but also for knowledge sharing.

There are no ubiquitous trusted sources.

We were most surprised to find that, with some important exceptions, trust in and loyalty to specific knowledge producers and disseminators seemed relatively low. No specific knowledge producer was cited as a trusted source by substantially more than 25 percent of respondents.

In the absence of prior benchmarks, it’s hard to know what this finding really means. On the one hand, trust toward knowledge producers could be (and we think should be) higher than it is. On the other, it’s possible that a 25 percent market share of trust is, in fact, high for the philanthropic sector. Perhaps we funders are a wary audience, not quick to trust in general. Or perhaps the nature of the power dynamics at work—where funders are used to being pitched and persuaded—puts them more “on guard.” The fact that many knowledge creation and dissemination organizations in the sector are also either fundraising or operating fee-for-service offerings might also affect trust levels.

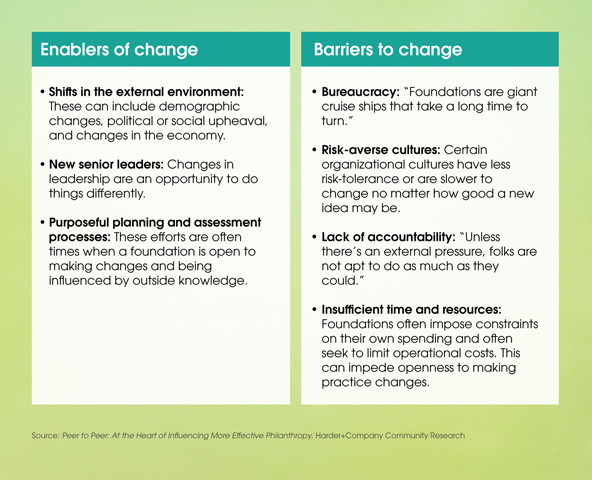

Knowledge alone is insufficient for making practice change.

Last but certainly not least, for a knowledge product to catalyze or contribute to change, it must be part of a larger process that includes trust, accessibility, peer support, organizational readiness, and leadership support and interest. Change is a complex process, and knowledge is but one piece of the puzzle. Knowledge can spark or help catalyze change, but it’s rarely sufficient on its own.

Here are some of the enablers of and barriers to foundation practice change we identified:

When we embarked on this scan in partnership with the organizations we fund, our hope was that our findings would both help us better understand the assumptions embedded in our strategy, and provide grantees with more-nuanced and -relevant data to inform their work. It has succeeded at both. Together with the organizations we fund, we are committed to repeating this research in a few years.

Understanding that peers are a primary source in sharing knowledge about philanthropic practice has also caused us to reflect on our own role to date: Where have we been proactive about sharing and where haven’t we? With these findings in hand, we will be more conscious curators of the knowledge we amplify and share with our peers going forward.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Lindsay Louie & Fay Twersky.