(Photo by Shutterstock)

(Photo by Shutterstock)

So. You want to save the world, and you’ve got an idea that you think could go big. Maybe you’re just getting started, maybe you and your organization have been plugging away for a while. Either way, you can’t just do stuff. You need a strategy.

Notice that I didn’t say “you need a strategic plan.” One of my all-time favorite SSIR articles is “The Strategic Plan Is Dead. Long Live Strategy.” Read it, or at least ponder the title. The worst thing that ever happened to strategy was that it got jammed together with “plan.” As Mike Tyson helpfully pointed out, “Everybody has a plan until somebody punches them in the face.” If your strategy is frozen in a plan, then when that plan goes to hell, your strategy goes with it.

Don’t do it! Your strategy has got to be an independent, living thing that responds to changing circumstances and new information. It should be reviewed often, and the bias should be toward change. There should be a balance between brevity and detail, between simplicity and specificity. Above all, it should be in plain language. Jargon is sand in the gears of clear thinking.

A serious strategy for impact at scale requires two starting ingredients: a Big Idea and a Dream. Activity that is not organized around a Big Idea is just a bunch of activity; by the same token, A Big Idea without a Dream means a journey without a destination. (I don’t know how to tell you how to come up with a Big Idea, but here are some examples of what I mean: lay psychotherapists, affordable greenhouses for smallholders, locally managed marine areas, professionalized community health workers, and bundling farm inputs and training with microcredit.)

Are you enjoying this article? Read more like this, plus SSIR's full archive of content, when you subscribe.

I do know how to help you formulate a Dream, though: Envision a world in which your Idea has achieved its full potential. In essence, strategy is about the best way to get from here to there—for you, the most useful big-picture strategy is about how to get from wherever your Big Idea is now (here) to that distant Dream of full potential (there).

Step One: The Doer and the Payer

It’s very rare for a single organization to realize the Dream—an idea achieving its full potential—on their own. That’s why you’re not serious about scale—about the Dream—until you’ve identified your Doer-at-Scale and your Payer-at-Scale.

The Doer-at-Scale is whomever is going to implement your idea at the scale of the Dream. The Payer-at-Scale is whomever has pockets deep enough to pay for it. There are just three choices for Doer-at-Scale: 1) governments, 2) lots of NGOs, or 3) lots of businesses. Figure out which one is most likely to do the heavy lifting at Dream scale—it’s critical to the future of your idea and you’ll want to start exploring the feasibility of your initial hunch ASAP.

As to Payer-at-Scaler, most social ventures start with philanthropy, but that can only take you so far: you’ve got to find a Payer-at-Scale if you’re to achieve sustained acceleration. You’ve got three choices of Payer-at-Scale: 1) customers, 2) direct Big Aid, or 3) governments (through the allocation of tax revenues or Big Aid). Pick the one that mostly likely to be able to do the heavy lifting at Dream scale.

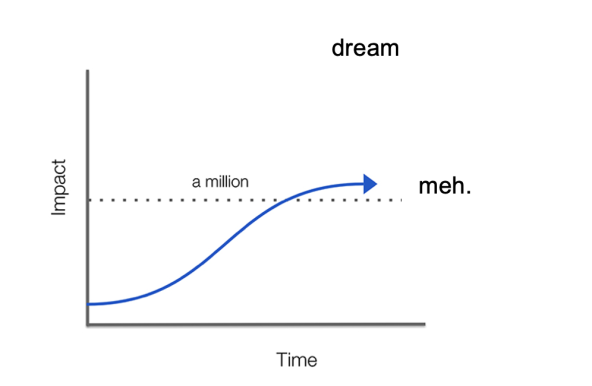

One of the most discouraging patterns in the social sector is the S-curve: a promising solution takes off, but then hits a plateau and never recovers its momentum. Too often it’s caused by failure to identify the Doer and/or Payer-at-Scale. Figure them out as early as you possibly can. We’ve seen too many great ideas hit an impenetrable ceiling way short of their potential. Don't let it happen to you.

Step Two: The Model

Once you have an Idea, a Dream, and a well-thought-out articulation of Doer and Payer, you have the bones of a strategy. What you need to do now is to lay out your idea as a model: a set of core elements that can be systematically replicated.

We’ve learned that scalable models can usually be expressed as a set of, say, four-six elements, something like this:

Idea: Professionalized Community Health Workers

- Salaried: paid as certified professionals

- Skilled: trained in proactive care across a broad set of conditions

- Supervised: part of an effective structure with on-site mentoring

- Supplied: connected by effective last-mile logistics.

Here’s another one:

Idea: Lay Psychotherapists

- Recruitment: screening for depression at clinics and churches

- Therapy: simplified, adapted cognitive behavior therapy

- Therapists: laypeople trained to deliver

- Delivery: weekly group sessions for eight weeks

- Support: active encouragement of groups meeting indefinitely

If you can’t extract and articulate a limited set of core elements, there’s a good chance that you don’t have something scalable. Simplicity will not only make it easier to navigate the necessary iteration ahead but, not incidentally, it will make it much easier for you to communicate what the hell it is that you do.

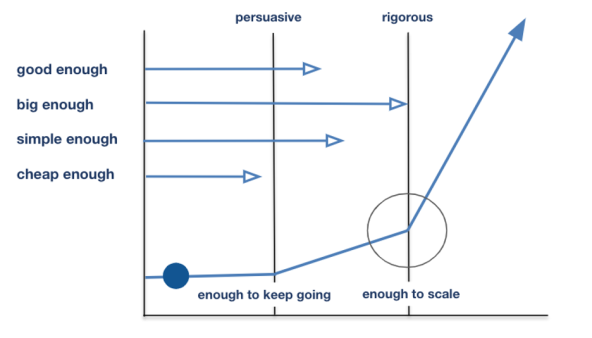

Moreover, because you already identified your Doer and Payer, you can lay out what you need to do to make your model as scalable as possible. There are four important things to think through here, what we collectively call “The Enoughs.”

Your model needs to be:

- Good Enough: It has to be worth scaling. This means: 1) an effect size (an improvement in health, learning, environment, income, etc.) big enough to matter in the lives of those you serve, 2) rigorous impact evidence to prove that your idea is worthy of scaling, and 3) a strong case for lasting change—how the behavior(s) that drive impact will be sustained over time. The articulation of how you’re going to address each of those is likely be the place where you put in the most time and effort.

- Big Enough: Your model has to adapt well to a broad set of local circumstances: the overlap between the size of the need and where your model would work roughly defines the potential of your idea. What constitutes “big enough” is up to you (We like to think of it as “making a big dent in a big problem”). What is really at issue here are constraints: What’s in the way of greater potential? What are the constraints to broad replication and how might you overcome them? What can you do to make it adaptable to a broader set of circumstances, and should you go work where there are more Doers and Payers available to you?

- Simple Enough: This means “simple enough for your Doer to do.” This is why the Doer-at-Scale is so important: you have to constantly design and iterate with your doer in mind. If you don’t, you could end up with a dead-end solution. We like to use the “doer-analog” as a tool: if, say, government is your Doer-at-Scale, then you need to find something analogous to your model that governments already do, and do reasonably well.

- Cheap Enough: This means “cheap enough for your payer to pay.” This isn’t just about “cost-effectiveness.” It's about understanding how decisions are made by your putative payers and their price point. Everyone has a price point, whether it’s a mom buying a cookstove or a finance minister budgeting for a primary health care program. You’ve got to figure out that price point: it doesn’t matter if you and your buddies think something is cost-effective if the minister doesn’t want to pay for it.

Step Three: The Dot

If strategy is about going from here to there, you’ve got to figure out where here is. To help figure that out, we break the scale journey into three stages: R&D, Replication, and Scaling.

- R&D: You’re a lab. You start with an idea and you iterate as rapidly as possible to turn it into a systematic, replicable model. It’s done when you can make a persuasive case for impact and that the model is scalable (though it’s still too early to be fully rigorous).

- Replication: You’re growing. You’re more like a factory, although you still have a lab. You’re churning out replication of your model while you continue to iterate on it. You’re growing, not scaling, while you work out all the operations, the systems, and the monitoring and evaluation that will make your model maximally replicable. You get big enough to explore economies of scale and achieve sample sizes big enough to generate rigorous evidence of impact. You can move on when you’ve made a rigorous case for both scalability and impact, using RCTs and/or other rigorous evaluations. This factory stage is mostly about what people refer to as “direct delivery.” (Funders often want you to grow for growth’s sake. Don’t. Be strategic.)

- Scaling: You’re becoming an “industry-builder,” mostly involved in the generation of other factories, of replication by others. You may still have your own essential lab and factory, but you’re increasingly focused on recruiting other doers and helping them replicate the model at good-enough quality. (Funders: Fund this! This is the impact jackpot! You don’t get enough chances to have this kind of leverage.)

Given these criteria, estimate where you are and “place the dot” as in the figure below. That dot will tell you much of what you need to know about your priorities in both the near and medium term. Ask yourself, “What do I need to do to move up the curve?”

Sequential “placing the dot” It can also help you track progress through the stages. You can also adapt that same graphic to track your progress on the “Enoughs” toward the “enough to scale” finish line.

There’s nothing precise here, but having to think about and commit to how far along you might be is super-useful.

Step Four: The Big Shift

The Big Shift is the collective set of activities that will drive sustained acceleration toward the Dream. There are five of them (there are probably more, but these are the ones that seem to matter most). To varying degrees, all are essential:

- Doer-at-Scale: How, at a big-picture level, are you going to transfer the burden of replication from your shoulders to the Doer-at Scale? There are a lot of possible strategies out there: a business focuses on the profitability that will attract others to the idea; an innovating nonprofit gets some BINGOs to replicate their solution as a step to government take-over; or the innovating NGO figures out a way to efficiently reach, persuade, and train a host of local NGOs. Take your best shot: this is usually the most important piece of the mechanics of scale-up. Sometimes you have to explore more than one Doer to arrive at the one with the most potential.

- Payer-at-Scale: How are you going to move from philanthropy to funders with deeper pockets? Work your way up the philanthropy food chain until you can attract “Big Bet” funders? Get enough customers to obviate the need for further equity rounds? Become a subcontractor in a big USAID grant and parlay that into bigger USAID funding? Today’s version might look naive to you in a couple of years but you have to start somewhere, and that means writing it now.

- Tech: Tech isn't a solution in and of itself, but it can accelerate solutions by extending reach, lowering transaction costs, and driving better performance. The question is not whether tech can help you, but how. Keep abreast of trends; watch what others in your sector and beyond are doing. Develop a point of view and learn who to work with. Set down your current best take on what you need and what you think is out there.

- Policy: The farther you get, the more you come to understand the policy changes that will open doors or lower barriers. Lay out your best thinking on what policies need your attention and what kind of talent and team it will take to help make change happen. Most organizations don’t spend nearly enough time, thought, or money on policy: they don’t think about it early enough and they don’t plan it well enough. Clarity about the policies you need to change, and the potential to change them where you are can help you think about one of the biggest strategic questions of them all: “Am I in the right place?” Banging your head against the wall in country X when country Y has the policy environment you need helps no one.

- Collective Action: You aren’t going to realize the Dream without allies and collaborators. Sometimes there is already a movement to join; sometimes you need to spearhead one. My favorite approach is the emergent doer collective as exemplified by the Community Health Impact Coalition (CHIC), which was formed by a bunch of organizations focused on professionalizing community health workers. Collective action can give a push to all of the other elements of the Big Shift—it can even turn the whole enterprise into something that looks like the elusive animal known as “systems change.” Figure out who might be there for you.

There. That’s it. Four conceptually simple steps, yet hard to do well, and essential to do well. Do the necessary thinking with your team, your board, and whomever else you find useful, and then get writing. Version one will be a bit ragged, but I promise it will represent a watershed in the clarity of your thought and communication around scale. And that, crucially, makes both the Dream and the journey to achieve it something that will rally your team and a growing circle of supporters.

By this time, you’re probably wondering, “What about the plan? Don’t I need a plan?” Of course you do! You have to take effective action and lots of things require you to plan ahead, and the thought you put into your strategy should reveal your most critical priorities (at any point in time, that is the most important function of strategy). But the world is a chaotic place. For most things, it doesn’t make much sense—and can be limiting—to plan more than three years out. Even then, you should review and refresh at regular intervals. A rolling three-year plan with an annual refresh is a good idea. Hell, you might just want to do a one-year plan. A stale plan is as useless as a stale strategy.

Your Idea and your organization have to swim in an ever-changing sea. Expect to be tossed around, but don’t let it shrink your ambitions. Instead, keep a fix on the Dream, and adjust your strategy as you explore and learn. The only thing that should be sacred is lasting impact in the lives of those you serve.

Formulation, iteration, and adjustment of strategy are skills. You get better with practice, so get on it. Your Dream deserves no less.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Kevin Starr.