(Illustration by iStock/hatchakorn Srisook)

(Illustration by iStock/hatchakorn Srisook)

About 10 years ago, a development organization and a national government took an innovative approach to a problem, the fact that people with chronic diseases were stopping their medical treatment before it was complete. After discovering that taking the medicine at the clinic was a major barrier for patients, the relatively new behavioral insights team found that allowing people to take the medicine at home (with a doctor or nurse on a camera phone) doubled the number of patients who took the entire course of medication (from 43 to 87 percent).

This was innovation. And yet, despite how many more behavioral insights trials have been run by intrapreneurs in this organization—often supported by the in-house innovation team—this kind of behavioral insights is still considered “innovative.” The approach has not (yet) been brought to how business is done on a regular basis.

By contrast, in the decade since intrapreneurs in the Western Cape Government in South Africa first initiated behavioral insights trials, it has come to occupy a secure place in the government’s toolkit. Public servants know when it’s appropriate to take a behavioral approach, and they are supported with in-house expertise and guidance. In a distinct and dramatic sense, behavioral insights have been adopted.

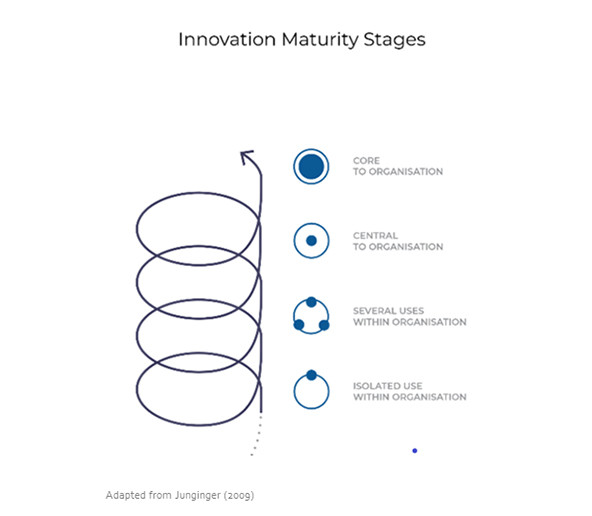

The adoption of innovation means an innovation has ceased to be “innovative.” It means that a method, technology, or approach to a problem has moved from the experimental edges of an organization to the core of its work: no longer a novelty, but something normal and institutionalized.

Are you enjoying this article? Read more like this, plus SSIR's full archive of content, when you subscribe.

However, the concept of adoption is rarely discussed, and the experience and know-how to bring it about is even less common. While an increasing evidence base has been developed on adopting digital systems in development and public sector organizations, as well as literature on organizational reform, little has been published on strategically moving approaches and technologies out of the innovation space to the mainstream of how organizations work. The most relevant insights come from institutionalizing behavioral insights in governments, mainly in public sector entities in the global north. This gap makes it all the more important to surface the challenges, opportunities, and factors that enable adoption, as well as the barriers and roadblocks that impede it.

Adoption and Scaling

Adoption is not the same as scaling. Broadly speaking, scaling means “taking successful projects, programs, or policies and expanding, adapting, and sustaining them in different ways over time for greater development impact,” as the authors of the 2020 Focus Brief on Scaling-Up put it. But scaling tends to involve different players and focuses on a specific service, product, or delivery model. For example, SASA! Raising Voices is a community mobilization approach to address and reduce gender-based violence which was first pioneered in Tanzania, but after being rigorously evaluated, has since then adapted in at least 30 countries by more than 75 organizations around the world.

By contrast, the adoption of innovation refers to one organization and how this entity brings what was once novel to the core of how business is done. Take adaptive management in USAID: After first being pioneered in the early 2010s in USAID country missions, it has since been tested, refined, and largely institutionalized as a standard way to design and implement programs. This means it is no longer a novelty requiring a burden of proof; instead, adopted approaches are now part of the organizational toolbox. People know what they are, when and how to use them, and who to ask for help in doing so.

Our work focuses on how a development organization can become an informed user or supporter of a novel approach or technology, which is not quite the same as adopting specific services, products, and delivery models and making them part of what an organization does (as with the Government of Bihar adopting the “Mobile Academy” program for women’s health, or UNICEF adopting “Wash’Em,” both programs that, having already proven their impact, could be taken up and expanded elsewhere).

Approaches and technologies that are introduced with an “innovation” label have been harder to adopt. Human-centered design, unmanned aerial vehicles, behavioral insights, and blockchain still largely sit solidly in the innovation space, in some cases almost a decade after first trials started within organizations.

Obstacles to Adoption

- The lure of novelty: Hype cycles, particularly those on emerging technologies, can have a disproportionate influence on senior management. But when attention, energy, and demand shift to the next new thing, it can be challenging to keep a focus on “old” innovations that may still need years of time and financial investment to be fully normalized.

- Team traits: Some organizations have dedicated innovation teams that typically commission innovations and offer technical support across the organization. These teams are often overstretched and lack the bandwidth or mandate to focus on the adoption of innovation. Even if they do, adopting innovation (as we will see below) demands a skill set more akin to organizational change than innovation, while these teams often have little influence on the entire institution and its ways of working.

- Misaligned incentives: The organizational metrics to track innovation efforts and investments often incentivize innovations to be labeled as “innovative” rather than normal. For example, a multilateral organization’s results framework tracked the number and percentage of “innovative tools and methodologies that are being piloted or scaled,” which disincentivizes adoption as the organization seeks to report a high number of projects that test or scale innovative tools and methodologies. For this reason, behavioral insights or tools such as satellite imagery will continue to be labeled as “innovative” and there is no metric that incentives moving work with such approaches and technologies out of the innovation space.

- Time tension: Innovation efforts usually have short-term investments as they either fall under standard three to five-year program cycles, or even shorter funding support (often the case for Innovation Challenge Funds). This short-term timeframe does not reflect the fact that adoption often takes multi-year investment and support.

- Islands of excellence: Organizations do not innovate, people do. In international and local development organizations, meaningful innovation is usually advanced by above-average intrinsically motivated individuals pursuing better outcomes for specific place-based challenges. Together, these individuals form islands of excellence. When these people move on, their ideas and the momentum they have created often leaves with them. Often, these individuals prefer to stay below the radar and make good work happen for specific development challenges. Changing an entire organization is not their primary goal.

- Overselling potential: In the bid to promote the adoption of innovation, it’s easy to over-sell the potential of methods, approaches, or technologies. Approaches and methods such as human-centered design, behavioral insights, or agile management require customization to context and a clear framing of when they add value.

What works?

Some organizations have made good progress on adoption: USAID has worked to institutionalize “Collaborating, Learning and Adapting” (CLA); the UK Foreign, Commonwealth, and Development Office (FCDO) have invested to strengthen institutional capabilities on behavioral insights; the German Agency for International Cooperation (GIZ) have ongoing efforts to enable its staff and partners to utilize blockchain technology; and the French Development Agency (AFD) is aiming to mainstream experimentation across organizational practices through its intrapreneurship program. Other bilaterals are early in their adoption journeys, often working on the adoption of approaches like agile, human-centered design, or behavioral insights rather than technologies. For many, the very concept of adoption is still new.

From our conversations with development professionals, we have found significant similarities in the journeys of those that have successfully adopted innovation. It’s likely to start with a series of unconnected experiments that are brought into a cohort to learn from one another. The next steps happen in parallel and usually span four to six years:

- In partner countries, more experiments take place using the innovation, resulting in more evidence on comparative advantage, limitations, and impact.

- An intentional innovation portfolio is designed to learn in service of adoption efforts. For example, if behavioral insights have shown positive effects in the field of governance in middle-income contexts, then the portfolio is increased to test how it works in other thematic areas, or in countries with other characteristics. This gives information as to whether adoption is the right decision.

- An explicit organizational change process gets underway, led by a team with a mandate for the adoption effort. The team formulates a vision for adoption (expresses why it’s important, and what difference it will make), sets boundaries (what the organization will and will not work on, related to the innovation), and works with partners and allies.

Innovation Characteristics

Before starting the journey to adopt innovation, it’s critical to reflect on certain characteristics of the innovation, which include:

- Relevance: Confidence that an innovation can help address a relevant problem. For example, many development efforts require behavior change, so behavioral insights might be of value.

- Observability: Ability to demonstrate and evidence a positive impact from this innovation (compared to how things are done currently). This includes demonstrating cost-effectiveness, as it is often easier to unlock smaller amounts for country-level experiments than the multi-year investments in organizational change needed for adoption.

- Adaptability: Capacity of the organization to adapt and build institutional capabilities. This includes aligned core processes and systems, and coherence between old and new ways of working. The successful cases of adoption we observed involved introducing complementary ways of working that align to how people think and behave.

- Sustainability: Resources to enable staff and potentially partners to leverage a specific method, approach, or technology. Often this means recruiting and retaining specialized staff and building longer-term investments into costing models to sustain new ways of working.

Once confident that the innovation meets these basic characteristics, it’s important to articulate and tap into a vision for how to adopt the innovation. What will our organization look like in five years, once we have adopted this innovation? Aligning around this vision will build commitment and momentum, and create the space to “think backward”: to articulate what needs to happen to reach this vision of the future.

Adoption Factors

We have identified five adoption factors that enable (or inhibit) adoption of innovation. This list is not exhaustive, nor are these factors binary (e.g. simply present or not present); they occur on a spectrum, even within an organization.

- Clear mandate: There is an organizational commitment to adoption. This means there are resources (time and budget) allocated for a team to lead or coordinate adoption (and incentives in place for others to collaborate), while senior leaders model and promote the innovation, working to remove barriers to adoption.

- Culture of collaboration and learning: The organizational culture supports adoption. This means collaboration—high levels of connectedness, trust, knowledge of others’ work, and drive to collaborate between different teams or divisions—as well as processes and managers who support people and teams to take risks, fail fast, learn, and share the learning internally and externally.

- Context: The organizational context enables adoption. This means alignment with priorities—in which the innovation supports key organizational priorities, or is itself a clear priority—as well as an administrative environment in which policies are agile, minimal, and speak to fundamental values and drivers. This also means procurement and contracting processes are flexible enough to enable experimentation and enable adoption.

- Collaboration: Networks allow for uptake and emergence, both external and internal. The organization is well connected at all levels with other organizations mainstreaming the innovation as well as internal networks making people aware of the innovation's value, and promoting its use, across organizational silos.

- Capacity: Key team members have relevant skills, experience, and confidence: sufficient experience of managing complexity and organizational change (a different skill set to innovation) as well as experience working in agile and flexible ways and building internal alliances. Key staff are confident to challenge norms, try new things, and share stories that support adoption.

In our research, we found that teams that strategically consider these factors and pursue an explicit vision for the adoption of innovation have achieved considerable progress in their organizations. This includes USAID and the institutionalization of adaptive management, the UK FCDO and behavioral insights, GIZ and the informed support of blockchain technologies, Korea’s International Cooperation Agency and its work on digital technologies, and others. The intrapreneurs who pursued adoption efforts all had the intent to move what was once novel out of the innovation space and make it part of their organizational toolkit. They were cognizant to not oversell the potential of novel approaches and emerging technologies, and to align applications to core business processes.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Benjamin Kumpf & Emma Proud.