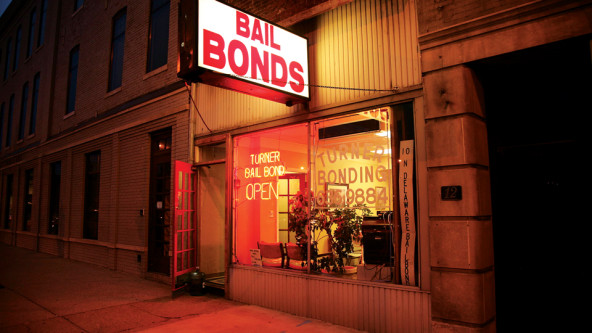

Turner Bail Bonds in downtown Indianapolis, Indiana, is open 24 hours a day, seven days a week to help clients who have been arrested to secure bail. (Photo by Daniel Schwen via Wikimedia Commons)

Turner Bail Bonds in downtown Indianapolis, Indiana, is open 24 hours a day, seven days a week to help clients who have been arrested to secure bail. (Photo by Daniel Schwen via Wikimedia Commons)

The Vernon C. Bain Center—nicknamed “The Boat”—is a giant jail barge that floats at the tip of Hunts Point in the Bronx. It sits between a fish factory and a sewage processing plant. Rikers, the sprawling island jail, is visible in the distance.

“It’s where wealthy New Yorkers put the things they don’t want to see,” Yonah Zeitz, a 23-year-old project associate with the Bronx Freedom Fund (BFF), tells me during our hike to the barge. “Out of sight, out of mind.”

No subway trains run nearby. A lone bus line drops off anybody who has business with the Boat a long way away, requiring a walk up a long, fenced road edged with razor wire. When you consider that a majority of the Boat’s inmates have not yet been found guilty of a crime—yet might have their freedom taken away for days, weeks, months, or years before the trial—and that most are black or brown, the conclusion Zeitz has reached is not as far-fetched as it might sound. “It’s like a modern-day slave ship,” he says.

Zeitz has come to the jail to free an inmate by posting his bail. Carrying cashier’s checks (it’s not a good idea for “bail disruptors”—a term coined for BFF staff members who post bail—like Zeitz to carry large wads of cash), he fills out the paperwork and meets with the inmate for about 20 minutes to offer to pay his bail and assess his needs. Once the paperwork goes through, the prisoner should be released in a few hours.

BFF will set up the accused with whatever he needs to attend his appointed court date—a MetroCard for public transit, child care, or reminders about his court appearance. In fact, the fund’s ideal outcome is to post bail before a person goes to jail, since even a few days in detention can be disruptive and traumatizing.

If he makes his court appearance, BFF will get its money back. It can then spend that money on another person stuck in jail because he can’t afford bail. In a revolving bail fund, almost every dollar comes back and can be used to help another person.

For nearly a decade, the Bronx Freedom Fund has helped defendants shorten or avoid pretrial detention and then made sure they appeared in court. Celebrities like Jay-Z and John Legend, and governors around the country, have taken up the cause of bail reform, with shocking brutalities like the treatment of Kalief Browder galvanizing activism around the issue. At 16, Browder was jailed in Rikers after being falsely accused of stealing a backpack. He spent three years in the notoriously violent jail, where he was beaten by inmates and guards and placed in solitary confinement. He suffered PTSD, depression, and anxiety, and two years after he was freed, he hanged himself.

Coinciding with heightened public concern about mass incarceration and the problems associated with cash bail, the Bronx Freedom Fund has gone national, with a second 501(c)(3) organization called the Bail Project. In a sense, BFF can be viewed as a decadelong pilot program demonstrating proof of concept that’s now being scaled to other parts of the country, with bail disruptors at each location posting clients’ bail, helping them appear in court, and returning the money to the fund.

The Bail Project recently received a $30 million grant from the Audacious Project, a collaborative philanthropic fund linked to TED that aims to bolster “jaw-dropping ideas with the potential to spark change.” The Bail Project is one of 10 big bets that Audacious is backing. With this cash infusion, the Bail Project plans to open 40 sites across the country and pay the bail of 160,000 people in five years. It’s already begun operating in Tulsa, Oklahoma; St. Louis, Missouri; Detroit, Michigan; and Compton and San Diego, California. In the last city, the project focuses on immigrant clients.

The project’s ostensible goal is to help inmates avoid pretrial detention. At the same time, it aims to drive reforms that eliminate the very need for such help. “We use our data and our stories to perform advocacy to create change,” Elena Weissmann, director of the Bronx Freedom Fund, explains. “So we can go out of business!”

At the same time, BFF cautions that as the call to “end cash bail” goes mainstream—even occasionally viral, with celebrities and other public figures taking up the cause—lawmakers must ensure that cash bail is not replaced with other unjust and coercive systems, such as judges’ simply not letting anyone out on bail, or risk assessment tools that might reproduce race and class disparities.

“We need to end unaffordable cash bail, and we’re creating a blueprint for what that could look like,” says Camilo Ramirez, director of communications for the Bail Project. “We need to have an alternative pretrial system grounded in the presumption of innocence for everybody.”

Financial Incentives

Bail is a set of conditions that a suspect must meet to obtain release before the trial, set by a judge during a suspect’s arraignment. Cash bail requires that the suspect or her friends and family raise money in exchange for her release. If the suspect comes back to court, they get their money back; if she doesn’t, they forfeit the cash. It’s supposed to give defendants a financial incentive to show up to court.

In reality, it means that hundreds of thousands of poor people are imprisoned before they’re convicted of a crime because they can’t pay their bail. According to the Prison Policy Initiative, there were 646,000 people in local jails in the United States, and 70 percent were being held before being convicted of a crime. “Most of my clients can’t afford any bail,” says Scott Hechinger, a public defender in Brooklyn, “and judges routinely set bail higher than they can afford.”

Charges can be inflated to justify pretrial detention. Over the week of Thanksgiving last year, Hechinger had a homeless client in Rikers facing a charge of violent burglary. Defenders of cash bail might argue that the current system did what it was designed to do by keeping a violent criminal from roaming the streets, robbing passersby at gunpoint. In fact, the man, who was homeless and addicted to heroin and crack, walked into a lobby of a building and took a package.

“Now, obviously, you shouldn’t take people’s packages,” Hechinger says. “But ‘violent burglary’ is an extreme charge given what he’d done.” Harvey Weinstein, the New York City movie producer accused of the actually violent crime of sexual assault, walked in, posted bail, and walked out, free to build his case against his accusers on the outside. The system worked for Weinstein. Meanwhile, other New Yorkers don’t get the same legal presumption of innocence.

Only 10 percent of New York City’s inmates are able to afford bail. Without BFF’s help, 90 percent end up pleading guilty, even if they didn’t commit the crime. “And we’re supposed to be a progressive state,” Zeitz points out, hitting on one of the reasons why the fund started and flourished in the Bronx: The poverty-stricken borough is in a Democratic state, in a progressive city. Yet, injustices like the Boat—which was supposed to be a temporary solution to the overflow from other jails—are a reminder that justice varies widely for the rich and the poor.

Unlike bail bondsmen—whose for-profit businesses, advertised in flashing lights, surround the Bronx Hall of Justice—BFF doesn’t collect interest or apply fees. The Freedom Fund’s no-strings-attached help means the difference between an inmate languishing on the Boat versus being in his community, in a better position to prepare a defense, and without burdening friends and family with fees. “The Boat is the worst place to be at,” BFF client Donald explains in a testimonial. “I was there three weeks. I thought I was gonna miss Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Year’s,” he said. “And then the Bronx Freedom Fund told me they were going to pay my bail. Y’all guys let me know I still existed in the world.”

This Passes for Justice?

The Bronx Freedom Fund grew out of the Bronx Defenders, a nonprofit that takes a holistic approach to criminal defense. In 1997, public defenders Robin Steinberg and David Feige, along with seven other lawyers, started the Bronx Defenders to help their clients with an array of needs that might spring from a criminal charge. To this day, instead of briefly representing clients in criminal court, the lawyers assess their needs across a spectrum of concerns. Does a criminal charge threaten their housing? They help with housing court. Custody of their kids? Family court. Troubles with immigration authorities? Immigration court.

Robin Steinberg, CEO of the Bail

Project, was a Bronx public defender when she launched the Bronx Freedom Fund with her husband, David Feige, in 2007 to help their clients post bail. (Photo courtesy of The Bail Project)

Robin Steinberg, CEO of the Bail

Project, was a Bronx public defender when she launched the Bronx Freedom Fund with her husband, David Feige, in 2007 to help their clients post bail. (Photo courtesy of The Bail Project)

“If you weren’t providing support and advocacy, you might do more harm than good,” Steinberg explains. The crushing caseloads that many public defenders face can hamper them from doing a good job helping their clients.

Steinberg is in her early 60s, with shoulder-length gray hair and a wide smile. She radiates an intense sense of purpose that wipes away any doubts she’d give up on a cause she believes in, no matter the obstacles. After hearing her pitch, it’s hard to believe that anyone who has any affinity for American values could ever tolerate cash bail and mass incarceration. “Freedom: a concept so fundamental to the American psyche that it is enshrined in our Constitution,” she argued to a packed auditorium at a 2018 TED conference. “And yet, America is addicted to imprisonment. From slavery through mass incarceration, it always has been.”

Born and raised in New York City, Steinberg graduated from the University of California, Berkeley, in 1978 with a degree in women’s studies. She returned to the East Coast for law school at New York University, planning a career as a feminist advocate fighting for what are traditionally framed as women’s issues, such as equal pay and reproductive rights. Part of what drew her to NYU was a program called the Women’s Prison Project.

“Honestly, all I saw was the word ‘women’ in the title and I was sold,” she told an interviewer in 2016. “The fact that ‘prison’ was connected to the program wasn’t important. As it turns out, it changed my life forever.”

She spent her second year at NYU working with inmates at Bedford Hills Correctional Facility for Women in nearby Westchester County, New York, helping them to see their kids more frequently and get better health care. Meeting female prisoners recalibrated her priorities. “As I was doing that work, I listened to their stories,” she says. “I was struck by the fact that they were doing so much time. I could not fathom what good it did to have these women sitting in jail cells. And they were deeply disappointed by their public defenders.”

She also couldn’t help but notice the class and racial makeup of the population she was serving. “They were low-income, mostly black and brown women,” Steinberg says. “It made me curious and angry.” She joined the Criminal Defense Clinic the next year, representing clients charged with misdemeanors. “I walked into the courtroom and I was so appalled by, and felt so implicated in, the injustice. Long lines of low-income men and women, people of color, chained together in handcuffs,” she says. “I thought, ‘This is what passes for justice?’”

She vowed that she would become a public defender. After a stint with Nassau County Legal Aid, she ended up at New York’s Legal Aid Society, the largest provider of legal help to indigent clients in the United States.

In 1990, Steinberg joined the team that launched the Neighborhood Defender Service of Harlem. NDS combines the efforts of criminal and civil attorneys, social workers, investigators, and others to help clients in Upper Manhattan.

She met David Feige in 1995 when he joined NDS. When she decided to start the Bronx Defenders in 1997, she hired Feige first. “I remember we took a walk through Marcus Garvey Park back when it was still strewn with needles and crack vials, and Robin asked if I would join this new office in the Bronx,” Feige told the New York Times in their 2011 wedding announcement. “The truth, though, is I would have followed her anywhere.”

Their first office operated out of a tiny space next to a Radio Shack. Today, the Bronx Defenders has a staff of almost 300, handling thousands of cases every year.

Along the way, Steinberg realized that cash bail alone could ruin her clients’ lives. Even a few days in jail could lead to the loss of a job, stress, trauma, risk of physical injury, a coercive guilty plea, and a criminal record.

“We realized bail was a huge driving force of incarceration for our clients,” she says. “It’s the single most powerful coercive lever that got people to plead guilty to crimes, even if they didn’t do it. Even for sums as low as $250,” she says. “We were frankly appalled.”

A Great Return on Investment

Horrified by seeing firsthand the impact of cash bail on their clients, Steinberg and Feige decided to launch the Bronx Freedom Fund. But it wasn’t easy to get philanthropists to invest in the beginning. Bail reform wasn’t a popular issue back in 2007, and a bail fund of the type they proposed was unprecedented. They had no idea whether it would work; it’d never been tried before. Their first grant came from Jason Flom, the CEO of Lava Records, through the Flom Family Foundation.

In a 2018 interview with Medium, Flom explained why the issue of cash bail was so important to him. “The problem is that you get arrested for something, you don’t have money, you may be innocent or you may be guilty. You may be jumping a turnstile or some other benign situation like drinking a beer in the park or something, and then you end up in Rikers Island, one of the most dangerous institutions in the world,” he said. “I think that’s most people’s primal fear, right? Being locked up in a cell and subjected to all the horror that goes with that for something they didn’t fucking do.”

He went to his dad, Joseph Flom, for the money to start the Freedom Fund. The elder Flom had made his fortune as a corporate lawyer specializing in mergers and acquisitions, earning the nickname “Mr. Takeover” in the 1980s—and a whole chapter in Malcolm Gladwell’s 2008 book Outliers.

“Well, I went to him for money, you know, because once we came up with the plan, we needed to fund it, so I went to my dad, Joe Flom, and he was very supportive of the idea, so he put up half the money and I raised the other half, and that’s how we started it,” he said. “And amazingly, we started with $200,000 and I think there’s $190,000 still left. I mean, after bailing out over a thousand people, that’s a great return on our investment.”

Since the idea was new at the time, Steinberg closely tracked results. “Will they show up to court?” Steinberg wondered. “How will the system respond?”

In their first 18 months, they bailed out 150 people. In more than 90 percent of cases, their clients attended every court appearance, undermining the main justification for cash bail: the idea that a suspect must have financial “skin in the game,” as Steinberg put it in her recent TED talk, to come back to court.

On top of that, not one person bailed out by the fund ended up serving prison time. Half the time the charges were dropped. That indicated that prosecutors were overcharging BFF’s clients, hoping that a jail stint would induce them to take unfavorable guilty pleas.

Legal Backlash

But the justice system was not as thrilled by their results.

In 2009, Bronx Judge Ralph Fabrizio was surprised to see William Miranda, whose bail he’d set at $3,000, show up to court cleanly dressed, no handcuffs, having spent the time between his arraignment and his trial a free man. Miranda was facing two misdemeanor assault-in-the-third-degree charges—he’d been accused of punching and kicking two people on two separate occasions. Zoë Towns, then the fund’s sole bail disruptor, had gone to the jail and paid the money, and signed a contract saying that she would help Miranda appear in court and follow its orders.

Judge Fabrizio was not pleased that the fund had paid Miranda’s bail and launched an investigation into the group. As the Village Voice reported at the time, the fund submitted letters from multiple people they’d helped. One young woman was excited because she was able to finish high school instead of sitting in a jail cell before her court appearance. Another client thanked them for letting him be with his family ahead of his court appointment. Another man had feared getting deported, but after the fund covered his $750 bail, he was able to return to his children. “I was not able to make the bail because of my financial problems,” he wrote. “If it was not for the Freedom Fund I might have been held by immigration and possibly deported and not be able to see my family. The case was dismissed after five weeks.”

The judge was not impressed. He ruled that the fund was operating illegally as an “uninsured bail-bond business,” forcing the group to suspend services. “The Bronx Freedom Fund has avoided any type of oversight during its year and a half existence—judicial, regulatory, or otherwise—and this in and of itself is against public policy,” Fabrizio wrote in a June 2009 ruling. Fabrizio also suggested that the fund might be fueled “by criminal activity.” He worried about the fund’s relationship to the public defender’s office, Reuters reported at the time.

So Steinberg and others worked to change the law. Alongside New York State Senator Gustavo Rivera, they drafted legislation that would carve out an exception for charitable bail funds (nonprofit status does not prevent individuals associated with a group from lobbying for policy). The legislation they drew up passed both chambers—but in 2011, Governor Andrew Cuomo vetoed the bill.

In a statement, Cuomo said that helping poor people post bail was a “laudable goal.” Yet he compared the fund’s lack of regulation unfavorably with the for-profit bail bonds model. “Over time, laws governing the bail bonds business have been developed and refined to ensure robust oversight of an industry that is vulnerable to abuse,” Cuomo wrote. “Charitable bail organizations, as proposed under this bill, would not be subject to any of these protections.”

Another version of the bill, called the Charitable Bail Act, passed the Legislature in 2012, allowing the organization to reopen. Cuomo signed that one, stressing his opposition to the injustice of cash bail. “It is unacceptable for defendants to have to spend time in jail for low-level crimes they may have not committed simply because they are unable to meet the bail requirement,” he said. “This law to allow the creation of not-for-profit charitable groups to cover the cost of bail for poor individuals held on a misdemeanor charge will help ensure that the state’s justice system works for all defendants regardless of their income.”

Although his statement praised the fund, the emphasis on low-level and misdemeanor crimes constrains the activities of bail funds to this day. Public defenders are grateful for the legislation that allowed the bail fund to continue to operate and pave the way for others—including a fund in Brooklyn—but some public defenders, like Hechinger and others who work with the fund, bristle at the legal restrictions, such as the $2,000 limit that prevents them from posting bail for clients charged with crimes that sound more serious. Hechinger’s homeless addict, who was charged with violent burglary for taking a package, and Kalief Browder, who was initially charged with second-degree burglary, a felony, would not be covered.

A Bipartisan Turn

Yet Cuomo’s change of heart reflects a larger shift in how the public and lawmakers view criminal justice reform. The mainstreaming of the effort has been driven by many factors, but what has helped the issue gain unique bipartisan support are the shockingly high costs of incarceration—one of the main strains on state budgets—and the repeated realization through contact with America’s criminal justice system of how wasteful and unjust it can be.

This trend is a far cry from the 1980s and 1990s, when Republicans and Democrats raced to outdo each other with tough-on-crime policies at the federal, state, and city levels. Eric Sterling, a young congressional staffer on the House Subcommittee on Crime in the summer of 1986, recalls Democratic Speaker of the House Tip O’Neill commanding him to come up with a plan to toughen America’s crime laws, specifically around drugs. “The issue of drugs and crime was really being hyped by the Reagan administration and the news media,” Sterling says. “They were all looking at this, saying, ‘We need to crack down.’”

In 1994, President Bill Clinton signed the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act, which helped cement mandatory minimums and habitual-offender laws (“Three strikes and you’re out”) and added 100,000 more police officers to America’s streets. States around the country instituted their own tough-on-crime policies, such as Louisiana’s draconian repeat-offender law and California’s three-strikes law, which led to catastrophic overcrowding in those states’ prisons.

In cities, policies like stop-and-frisk and broken-windows policing criminalized more activities—standing on the street was loitering—and cracked down on minor crimes: Turnstile jumping was deemed “theft of services,” punishable by up to one year behind bars, a hefty penalty for $2.75.

In the aughts, the political winds started to shift, with the bipartisan tough-on-crime fervor of the ’80s and ’90s waning in the face of mass incarceration and its racial disparities. The push for criminal justice reform began to stretch across the ideological aisle. During the Obama administration, the Justice Department undertook a variety of policy changes to even out the racial disparities in the justice system, including undoing the racially discriminatory harsher sentencing for crack than for cocaine and freeing a record number of nonviolent drug offenders.

The Vernon C. Bain Correctional

Center at Hunts Point, New York, is the only prison barge in the United States. Its 100 cells house inmates from medium- to maximum-security. (Photo by David Howells/Corbis via Getty Images)

The Vernon C. Bain Correctional

Center at Hunts Point, New York, is the only prison barge in the United States. Its 100 cells house inmates from medium- to maximum-security. (Photo by David Howells/Corbis via Getty Images)

The potential for bipartisan consensus on the issue continued to grow, as Charles and David Koch, the billionaire philanthropists who fund libertarian causes, embraced criminal justice reform. “Though we may have arrived at our current criminal justice system through the actions of many well-meaning individuals, far too many of its features run counter to the basic principles of a free society,” the Charles Koch Institute explains on its website. Republican lawmakers who also identify as libertarian, like Kentucky Senator Rand Paul, have long championed reforming America’s prisons.

In the first two years of the Trump administration, former Obama administration adviser and progressive activist Van Jones worked with Trump administration officials—most notably Trump’s son-in-law and senior advisor Jared Kushner—to champion criminal justice reform. (Kushner is personally invested, according to media reports, because his own father served time in prison for white collar crime.) Jones and other reformers deftly navigated the chaos of the Trump White House to get a monumental new law passed through an embattled, divided 115th US Congress.

The First Step Act of 2018 shortens mandatory minimums, bans the shackling of pregnant women, ensures that federal inmates are placed closer to their families, and makes more people eligible for early release. It’s a long way from the “tough on crime” policies that dominated both the Republican and Democratic agendas in the 1980s and 1990s.

“What happened?” Van Jones and Jessica Jackson asked in an article on the CNN website. The two cofounders of #cut50, a bipartisan criminal justice initiative, were trying to explain how President Donald Trump, the same man who has yet to apologize for calling for the death penalty for the Central Park Five—the teenagers falsely accused of raping a white jogger—signed a prison reform bill into law.

“On the one hand, red state Republicans who had simultaneously cut both their own prison population and their crime rate weighed in heavily; they repeatedly prevailed upon Trump to update his thinking,” Jones and Jackson wrote. “Secondly, some key advisers underscored the political benefits to Trump of him championing an issue popular in the swing states.”

But the new law has its limits. It applies only to federal prisoners, a relatively small portion of incarcerated people in America. Bail reform, which occurs at the state level, is an easy sell to liberals and conservatives who want to see large-scale reform of the criminal justice system. People serving pretrial detention are legally innocent, so the elimination of cash bail is more politically palatable than, for example, early release for so-called violent felons.

Culture Eats Policy

BFF operates out of a new, bright office on a tree-lined street in the South Bronx, having recently vacated the Bronx Hall of Justice—an intimidating glass structure that sits on a sinkhole. “The symbolism is … it’s literally sinking,” Executive Director Elena Weissmann jokes. The building is bedeviled by so many problems, from leaks to mice infestations, that lawyers once nicknamed it “The Titanic.”

In the sunny new office, a picture of New York rap legend Christopher Wallace (The Notorious B.I.G.) occupies one square shelf of a bookcase; a judge’s gavel sits in another. The staff—about 10 people—is racially diverse and skews young. It’s early in the morning, and the new office’s heater is malfunctioning, but spirits and caffeine levels seem high.

Back when they operated out of the Hall, their clients would “get rearrested for really petty shit,” says Sara Rahimi, administrative associate, who is in charge of compiling data and writing reports. “It’s a really triggering place,” she adds.

Other parts of the New York City justice system also remain unenthusiastic about their work. “They play games with us,” says Weissmann about correctional officers at Rikers, who will occasionally pretend that a client they’re trying to meet is not at the jail. She says that many correctional staff members they interact with can be apathetic or hostile when they post clients’ bail.

In addition to helping clients, the group works to facilitate reforms. Their work with prisoners gives them a view of what’s happening, and they can then testify before the City Council.

Take, for example, a set of recent bail reforms passed more than a year ago by the state Legislature that are designed to make bail less traumatizing for inmates. They include allowing inmates to access their cell phones so they can reach out to relatives, and speedier release once bail is posted. Not earth-shattering, but helpful. Yet many of the reforms have stalled, meeting resistance from some correctional officers and other elements in a system that doesn’t welcome change.

“We’ve been tracking them very systematically, asking all our clients if they were granted their rights, like using public records to see when people are released, and we have found basically that implementation rates range from 0 percent to 20 percent,” Weissmann says. “Which is insane.”

And the harder bail is for their clients to navigate, the harder it is for the disruptors to do their job. Zeitz says he occasionally has to wait for hours and well into the night for his bail to go through.

Weissmann sees the glacial slowness of reform as a result of long-term culturally entrenched institutions and attitudes. “I think it’s just … culture eats policy? The laws are good. And City Council’s doing everything they can do,” she says. “They’re not hard to implement. One of them is just to put up a sign about how to pay bail, and they haven’t done that.”

She thinks that intentions are mostly good at the state level and in the New York City Council and that policy progress is being made. Yet, it seems harder to enact change on the ground. She points to prevailing attitudes about guilt versus innocence for poor defendants of color.

“I think there’s a whole culture of indifference and apathy and people waiting to retire and thinking that everyone in jail deserves to be there and why work at all to get them out?” she says. “Even though it’s in their best interest if we’re talking about … if their actual concern is their safety and people’s safety and costs, it’s totally in their best interests to get people out quickly,” Weissmann notes. “But that’s not the prevailing culture, and it’s not how people are trained.”

Despite the obstacles and setbacks, the fund continued to repeat its early successes, at much greater scale. It posted bail for 1,000 people last year, and they came to court at the same high rates: More than 95 percent made their appearances.

With an expansion into Queens—staff members work out of the Bronx office but also travel to Queens—their budget for next year is over $800,000, an increase over the $500,000 budget this year. Money from the original investment by the Flom Family Foundation is still circulating in the fund.

Spreading the Gospel

In January 2018, the Bail Project officially got to work taking the Freedom Fund model outside of New York City, when they started posting bail for people in St. Louis, Missouri. In St. Louis, bails are set as high as $50,000 for nonviolent crimes, prompting a columnist for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch to point out that a recent arraignment sounded like a luxury car auction. Most of the inmates were people of color. “I could not help but draw a correlation to slave auctions,” she observed.

St. Louis was a natural fit for the Bail Project. In the wake of the 2014 police shooting of unarmed black teen Michael Brown, Black Lives Matter protesters shed light on the shocking injustices perpetrated by the city and county criminal justice systems. As national attention pivoted to the protests there, criminal justice groups revealed abuses of cash bail and other ways the system is stacked against poor defendants. In 2016, the nonprofit ArchCity Defenders—a group that, like the Bronx Defenders, takes a holistic approach to public defense—sued the city of Foristell for holding people who were unable to pay fines. That year, a judge ordered the city of Jennings to pay $4.7 million to people held in jail for being unable to pay fines. The imposition of stiff fines—coupled with high cash bails—gives poor people no choice but to sit in jail, even if their point of contact with police occurred during something as benign as a traffic stop.

Inmates at the “hellish” St. Louis Medium Security Institution, also known as the Workhouse, await the arrival of temporary air-conditioning units on July 24, 2017. (Photo by Roger Cohen for The St. Louis Post-dispatch)

Inmates at the “hellish” St. Louis Medium Security Institution, also known as the Workhouse, await the arrival of temporary air-conditioning units on July 24, 2017. (Photo by Roger Cohen for The St. Louis Post-dispatch)

St. Louis also has its own infamous jail, called the Workhouse, a facility that holds 550 people, mostly awaiting trial. The conditions have been described as “hellish”: guards allowing sexual assault, providing poor medical care, and even having inmates compete in gladiator-style fights. Former inmates claim the facility is filled with mold, rats, and insect infestations. “I say all the time that the Workhouse is a hopeless place. When you first walk in, you can feel the hopelessness,” Inez Bordeaux, who once spent 30 days in the Workhouse awaiting a probation violation hearing, told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. “You can feel the desperation.”

The Bail Project’s St. Louis branch offers hope to people who can’t afford bail. Michelle Higgins, a St. Louis activist with experience in mass bailout actions in the area, was one of the first bail disruptors. “My hope is that I’m bailing out dozens of people weekly,” Higgins told the St. Louis American. The St. Louis branch encapsulates the Bail Project’s commitment to work with existing institutions, like the ArchCity Defenders, the public defenders’ office, and the St. Louis activist community.

In fact, Thomas Harvey, the executive director and cofounder of the ArchCity Defenders, left his post to become the Bail Project’s national director of strategic relationships and advocacy. “We’re really looking to build on the work that folks had already started in St. Louis,” Harvey told the St. Louis American about his new job. (He has since left to become justice project director at the Advancement Project, a civil-rights organization.)

The Bail Project’s St. Louis arm is already showing results. After expanding to the city and county of St. Louis, they helped bail out more than 1,000 people over the course of the year. So far, they’ve found similar return rates of 96 percent, signaling a success rate that matches the Bronx Freedom Fund’s. “It’s encouraging to see what we are seeing at the new sites,” Ramirez says.

A Big Bettable Idea

The ambitious 40-city rollout is paid for in large part by the Audacious Project, a fund for ambitious ideas that show potential to enact lasting change at scale. Anna Verghese, executive director of the Audacious Project, explains what drew the group to help bring the Bronx Freedom Fund to the rest of the country.

They first encountered Steinberg’s work in a 2016 Marshall Project article titled, “Bail Reformers Aren’t Waiting for Bail Reform,” which chronicled the growth of bail funds like the Freedom Fund. “Anybody will plead guilty to go home, and everybody knows it,” Robin Steinberg told the Marshall Project. “This model allows us to prove that point while freeing people in the meantime.”

There are a number of reasons the Audacious Project chose to fund the scaling of the Freedom Fund nationally. “Our criteria is, ‘Ideas that just really take your breath away. Ideas that are obviously ambitious and audacious—but have demonstrated a credible pathway.’” Verghese says. “The fund is self-sustaining; we liked the idea of returning money to the fund. It felt like it could be a real game changer in reforming mass incarceration.”

It helps that BFF has already demonstrated a striking success rate. “They have proof of concept,” she says. “It’s already working. It’s a plan to scale and has the potential to impact hundreds of thousands, maybe millions of lives.”

The Audacious Project operates with close to $450 million in funds for all of their investments. The Bail Project alone started with $24 million but has now spilled over into $30 million, Verghese says.

Other philanthropies, such as Bohemian Foundation, have also contributed. Seed money for operational expenses came from foundations. Yet more than 90 percent of their funds come from individual donations, almost all less than $10,000. “It costs just $39 to secure someone’s release,” they point out in their fundraising appeal. The median individual donation is $52. The money they get through fundraising goes into the fund. Nationally, the budget for the next year is $5 million, with a plan to top $30 million as the fund expands to 40 locations.

One challenge for scaling the project nationally is that bail systems generate different problems in different locations. Getting someone a MetroCard works in New York City but will not be very helpful in a place with no public transportation; in parts of rural America, staffers might need to figure out how to get indigent people access to a ride or gas money. The Tulsa location serves women inmates, primarily mothers held in pretrial detention at high risk of losing their kids. The city also lacks services more widely available in larger, wealthier locales.

In New York, even reasonable-sounding bail—like $250—might be impossible for inmates if they don’t have that money or the means to access it. In places like St. Louis and Compton, bail is so high that it’s more of a pipe dream than a realistic way to get out of jail before trial. The first time the Bail Project’s bail disruptors tried to pay someone’s bail in Compton, the facility didn’t know how to process the payment. “It’s glaring proof of the fact that cash bail is so unattainable that people just end up languishing in jail cells,” Steinberg says.

In Compton, the Bail Project is partnering with the UCLA School of Law and the Compton Public Defender to help clients and to track data. Ironically, California recently ended cash bail. But that doesn’t mean the Bail Project’s work is done. Last-minute additions to a bill signed by Governor Jerry Brown left criminal justice advocates deeply disappointed. Although the bill, set to go into effect in October 2019, will pulverize the for-profit bail bonds industry, critics fear that its replacement of cash bail with risk assessments and preventive detention will just lead to local judges’ deciding to keep people in jail before trial.

No More Talk

Before the bill’s signing, singer and criminal justice advocate John Legend (who sits on the Bail Project’s advisory board) urged Governor Brown not to be so hasty. “@JerryBrownGov #BailReform is needed, but NOT #SB10 which replaces the predatory for-profit bail system with a system that threatens to expand unfair incarceration of communities of color,” Legend tweeted.

Recently, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo has signaled that he intends to follow California and eliminate cash bail. “Cash bail means that if you’re rich, you get to walk, and if you’re poor, and you can’t make bail, you sit in jail,” Cuomo said at the 2018 Global Citizen Festival. “That isn’t justice. We’re going to end the cash bail system once and for all.”

Cuomo, like many politicians, makes lofty pronouncements that aren’t necessarily followed by policy change, so it’s not surprising that at the same event, John Legend made it clear to Cuomo and other governors that activists would not be satisfied with uplifting speeches—or reforms that risk reproducing the same injustices entrenched in the cash bail system.

“We have a lot of work to do,” Legend said. “We can’t just talk the talk. We have a lot of politicians talking the talk, and we’re going to follow up with them, right? We need legislation passed—we’d better follow up with you, Governor Cuomo. All our governors around the country: We’re going to follow up with you, and we’re voting. It’s not enough to talk.”

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Tana Ganeva.