Pawame Solar, a social enterprise that provides off-grid solar home systems to refugees in the Kakuma refugee camp in Kenya and employs refugees as sales agents, is one example of a refugee investment. (Image courtesy of Pawame)

Pawame Solar, a social enterprise that provides off-grid solar home systems to refugees in the Kakuma refugee camp in Kenya and employs refugees as sales agents, is one example of a refugee investment. (Image courtesy of Pawame)

More than three years into the pursuit of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), not one country is on track to achieve them by the 2030 deadline. This conclusion, reached in a recent Brookings Institution report, highlights the enormous human costs associated with not meeting these goals, and implores countries to do more. With heads of state slated to meet at the UN later this year for the first major progress check on the SDGs, it is high time we bring new and innovative approaches to economic growth and investing to bear on the world’s social challenges.

Refugees and forced migrants—a group that today amounts to a historic high of more than 70 million people worldwide—represent one such social crisis and are top of mind for many of us. Whether we’re reading about the turbulence in Yemen, Venezuela, or Syria, or at the US-Mexican border, or about any number of the 65 protracted displacement situations worldwide, we see suffering and hardships exacting a toll on millions of people. Indeed, forced migration is directly implicated in the attainment of nearly all the SDGs—even though the SDGs do not specifically address it.

Increased capital investment can make an enormous difference in creating long-term solutions to global forced migration, while also driving progress on nearly every other global development challenge. (Image from the Refugee Investment Network’s “Paradigm Shift: How investments can unlock the potential of refugees” report)

Increased capital investment can make an enormous difference in creating long-term solutions to global forced migration, while also driving progress on nearly every other global development challenge. (Image from the Refugee Investment Network’s “Paradigm Shift: How investments can unlock the potential of refugees” report)

So how can we begin to turn these dynamics around? If we subscribed to the dominant narrative surrounding refugees, it would be natural to conclude that forcibly displaced populations represent a burden to host societies, drive instability, and weigh down development efforts. Certainly, investors most often view investment in refugees as risky and thus, a “bad bet.”

Yet, there is good reason to revisit these assumptions and to sharpen our analysis of the perceived problems, risks, and most importantly, the opportunities associated with forced migration. When we do, the facts that emerge tell a different story, one in which refugees are motivated, hard-working, resilient, and often entrepreneurial people, who build successful businesses and enrich the communities where they live. While forcibly displaced people face serious challenges, often stemming from underinvestment, and backward and restrictive laws, research shows they are loyal, creditworthy, and investable. In fact, a closer look at how investors are helping refugees fulfill their potential reveals enormous opportunity.

Are you enjoying this article? Read more like this, plus SSIR's full archive of content, when you subscribe.

A Growing Market for Refugee Investments

The Refugee Investment Network (RIN) was established in 2018 to take this closer look at the manifold socio-economic issues affecting refugees, and to create new pathways for investment, jobs creation, and sustainable economic growth among forcibly displaced people. The RIN has set out to build the “connective tissue” to mobilize investment capital for refugee entrepreneurs. For our first major report, we interviewed entrepreneurs, impact and institutional investors, refugees, and humanitarians, as well as representatives from philanthropy, development, finance, business, and government to understand how best to invest in and with displaced people.

Our interviews, along with analyses of investment and refugee data, show that there is increasing interest in building the investment market around entrepreneurial refugees. They also revealed that first-moving investors come from a variety of asset classes and geographies, and have a range of returns and impact expectations.

The types of deals we’re seeing vary significantly. For example, many refugees face the stigma of their circumstances, as well as restrictive and discriminatory policy and regulatory environments, but in 2007, the Small Enterprise Assistance Fund (SEAF) looked beyond the news from Serbia and took a chance on Bosnian refugee Goran Kovacevic. At the time, Kovacevic was operating a grocery store chain called Gomex, with 16 stores and 306 employees. Boosted by SEAF’s 1.2 million Euro (about $1.4 million) investment, Gomex grew to 159 stores throughout Serbia, with nearly 1,000 employees.

Meanwhile, to mitigate both real and perceived financial risks, some investors are using “blended capital” and other creative financing structures in place of traditional investment approaches. For example, the private sector arm of the World Bank, the International Finance Corporation (IFC), and the Goldman Sachs 10,000 Women program partnered to create the Women Entrepreneurs Opportunity Facility (WEOF), a first-of-its-kind global loan facility for women-owned, small- and medium-sized enterprises. WEOF launched in 2014 with a $100 million investment from the IFC and $43 million from the Goldman Sachs Foundation. This initial capital incentivized other investors to co-invest in a previously unproven market and demonstrate the commercial viability of a new asset class, and ultimately led to targeted investments totaling nearly $1 billion. To date, WEOF has invested in financial intermediaries in 26 countries, including some of the world’s poorest and conflict-affected states. This capital has subsequently reached 50,000 women entrepreneurs with a goal of reaching 100,000 over 10 years.

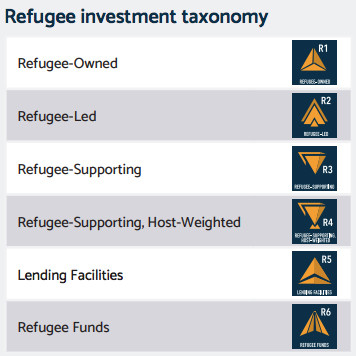

The RIN has developed an investor’s framework to qualify and track investments over time and to respond to the question: “What is a refugee investment?” (Image from the Refugee Investment Network’s “Paradigm Shift: How investments can unlock the potential of refugees” report)

The RIN has developed an investor’s framework to qualify and track investments over time and to respond to the question: “What is a refugee investment?” (Image from the Refugee Investment Network’s “Paradigm Shift: How investments can unlock the potential of refugees” report)

Defining “Refugee Investment”

While a variety of approaches are currently in play, other growing fields like gender lens investing have shown us that clear definitions and investor frameworks are important to building a market. Without them, investors are adrift, unsure how to identify, categorize, assess, or measure deals. To address this shortcoming, the RIN recently introduced a "refugee lens" to help investors from across the capital continuum qualify investments in refugees. The lens considers ownership, leadership, and an enterprise’s potential for change within the “refugee community” (which includes refugees and forcibly displaced people, as well as their hosts) to define types of investments.

Under this framework, refugees must at least partially own or lead the enterprise receiving investment, or that enterprise must support refugees through jobs and investment. It defines “refugee-supporting” investments as actions that positively affect the lives and well-being of refugees or their hosts through direct products and services, workforce development, or improved humanitarian delivery capacity.

Investors can use the lens not only to examine and weigh prospective deals, but also to assess whether their past investments qualify as refugee investments. Some investors may have backed into refugee investing unintentionally. Acumen, for example, invested in deals with a positive impact on displaced people, but the deals had more of a sector focus; in the case of its investment in the for-profit cotton ginning company Gulu Agricultural Development Company, for example, the focus was on agriculture rather than displacement.

This last point highlights perhaps our most significant finding: Forced migration intersects directly with 13 of the 17 SDGs. Take Climate Action (Goal 13) for example. Climate change is forcing growing numbers of people to leave their homes. Or consider Decent Work and Economic Growth (Goal 8). High youth unemployment and low economic growth can be a precursor to instability, violence, and ultimately, forced migration. The intersections between the global refugee crisis and the 2030 agenda are numerous and clear. Indeed, impact investors and funders who are only tangentially interested in or who don’t know how to engage in refugee investments need to pay attention: Investing in refugees is critical to achieving the SDGs.

In short, how we choose to engage with the world’s forced migrants—85 percent of whom reside in middle- and low-income countries—has the potential to either hold back or propel forward the attainment of the SDGs. With so many of the global goals tied to improvements in livelihoods, poverty reduction, and private sector engagement, innovative solutions aimed at driving sustainable investment into new markets like refugee investments merit serious consideration and engagement.

All Capital on Deck

Ultimately, building a vibrant refugee investment market will require the entire private sector to step up:

- Impact investors can apply the refugee lens to their portfolio, and “prime the investment pump” by providing angel and seed financing to support the creation of new ventures and the early growth of refugee-owned, -operated, and -supporting enterprises.

- Foundations and corporations can invest grant-based capital in innovative, sustainable solutions to forced migration; create and test new, pro-refugee mechanisms and models; advance research on refugees and data collection; invest in field-building and investment intermediaries; and incentivize and de-risk private investment in refugee markets through the extension of concessionary capital, which will reduce investor uncertainty and empower others to follow.

- Institutional and faith-based investors can provide the refugee lens to their investment committees and ask their portfolio companies or fund managers how their assets are benefiting displaced communities. Simply incorporating one or two questions into the diligence process—such as “how will the investment impact forcibly displaced people?” or “how might the investment have more of a positive impact on refugees?”—can move mountains.

As anyone in gender lens investing, or even impact investing, can tell you: It takes time to build a field. We are at the opening chapter of an unfinished story of human potential, but it’s clear that an emerging, necessary, and promising field of refugee investing is taking shape. Investors like SEAF are showing us the power of new private sector engagement, smart and sustainable investment strategies, and an entirely new narrative around refugees—as solid investment partners, full of potential.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by John Kluge & Tim Docking.