(Illustration by Nyanza D)

(Illustration by Nyanza D)

Many organizations endeavored to institute structural changes to racial equity efforts following the morbid booster shot effect of George Floyd’s murder on stagnant national conversations about race. Countless companies released statements, and some took actions that focused on anti-racism instead of mere inclusion. Yet, while attention to culture and new ideas can be modes of influence, organizations—whether dot org, dot gov or dot com—ultimately make their most significant changes through internal policy. Hiring and promotion policies determine an organization’s makeup. And this past year’s dramatic increase in remote work has demonstrated that institutions are not buildings or products—they are the talent: the talent that comes, the talent that stays, and the talent that leads. The importance of hiring and promotion in the workforce makes the problematic trope of the “hard-to-find” qualified Black candidate more than just a stereotypical cliché: its damaging effects are an enduring racist cog in the wheel of progress.

A Leader Says the Quiet Part Out Loud

Last spring during a Zoom meeting with staff, Wells Fargo’s CEO Charles Scharf said that the bank had trouble reaching its diversity goals because there was simply not enough qualified Black talent, reiterating in a company-wide memo: “While it might sound like an excuse, the unfortunate reality is that there is a very limited pool of black talent to recruit from.” Reuters reported that “Black senior executives across corporate America said they are frustrated by claims of a talent shortage, and called the refrain a major reason that companies have struggled to add enough racial and ethnic diversity to leadership ranks, despite stated intentions to do so.” By September, Scharf had apologized, calling his comment “insensitive,” and said that it reflected his “own unconscious bias.”

By using the language of “sensitivity,” the apology reduces the racial bias and its harmful effects to a matter of hurt feelings. However, Scharf’s words are more than indelicate; they harm worker confidence and sense of belonging. His words don’t just reflect a largely accepted way of thinking, they reflect the harm potentially inflicted throughout an entire career—in hiring, promotions, and organizational culture.

A Common Refrain

The Wells Fargo CEO is not alone. The beliefs that qualified Black candidates are rare and that Black employees are not as qualified for promotion as their white colleagues are real and far more common than many may realize. Within multiple organizations, hiring managers claim that they couldn’t diversify a program, team, panel, or advisory council because the Black candidates simply weren’t there to be hired. Whether hampered by a “tight timeline” or daunted by the “extra effort” of finding a qualified Black candidate, they insist that organizational diversity is too hard to achieve, not because of the efforts being made to do so, but because of the talent pool.

Darrick Hamilton, professor of economics and urban policy at the New School, has rebuffed the claim of some technology companies that there is a severe shortage of qualified Black and Hispanic candidates in Silicon Valley. The “claim does not hold water,” he contends, citing a USA Today report showing that Black and Hispanic computer scientists and computer engineers graduate from top universities at twice the rate that leading technology companies hire them. Dominant groups make the excuse that they “‘searched but there was nobody qualified,’” but, Hamilton observes, “if you look at the empirical evidence, that is just not the case.”

When business leaders ask if diversity should be more important than “merit,” this query betrays the false impression that these goals are mutually exclusive. Several hiring agencies and DEI professionals supporting organizational change have confirmed that this refrain is commonplace. DEI consultant Tamara Osivwemu says, “It’s definitely a trope. I’ve heard it from many clients, even those with the best of intentions—the ones really trying to do the work—who say, ‘We want to get diverse candidates, we want to do our part, but we absolutely can’t let our quality of work, or expectations suffer.’”

Foundational Fallacies

The foundation that both supports and perpetuates this set of harmful organizational practices is comprised of four primary fallacies.

Objectivity | The notion that there is a single, most-qualified candidate or employee is false. There is great variation in how two applicants with different experiences and skills would successfully perform the same role. Assigning a “most qualified” label is based on measures that are difficult to quantify and are nested in opinion. The rubrics used in hiring and promotion are highly subjective. This subjectivity can lead to false narratives that repeat stereotypes about applicant potential, assumptions often steeped in bias.

Meritocracy | Subjective criteria associated with likability still figure strongly into the hiring process, usually couched in the organizational language of "culture fit” and expressing a desire for candidates who are similar to the employer. Similarity plays a significant factor in this equation: more often than not, someone considered a “good culture fit” is someone “I’d want to grab a beer with,” someone “like me.”

Who is the “me” in this scenario? According to research on Fortune 500 companies, the majority of organizational hiring managers and leadership are white men. It is no surprise that a cycle of exclusion is perpetuated when most Americans have largely homogenous friend and peer groups and a large percentage of hiring happens through these networks. Per a LinkedIn survey, nearly 85 percent of jobs are filled through networking, making social capital, rather than so-called “meritocracy,” a critical element of hiring and promotions.

Equal Goal Posts | If organizations find it challenging to identify qualified Black candidates, it might be because racial biases have skewed the perception of “qualified,” moving the goalposts for both Black candidates and employees. A commonly held belief among many Black workers is that one needs to be twice as good as their white peers to simply be considered on par with them. Indeed, a six-year study found that people of color had to manage their careers more strategically than their white colleagues and to prove greater competence before winning promotions.

Bad Apples | Hiring and promotion practices are often executed at the individual level, which can lead to the misconception that problematic behaviors are one-off occurrences. It can be difficult to see the systemic nature of this sort of workplace racism. Akin to the “bad apple” concept in policing, many managers and those in leadership positions are comfortable considering these practices as merely individual occasions of unconscious bias rather than products of a system-wide failing.

The Individual Burden of Workplace Racism

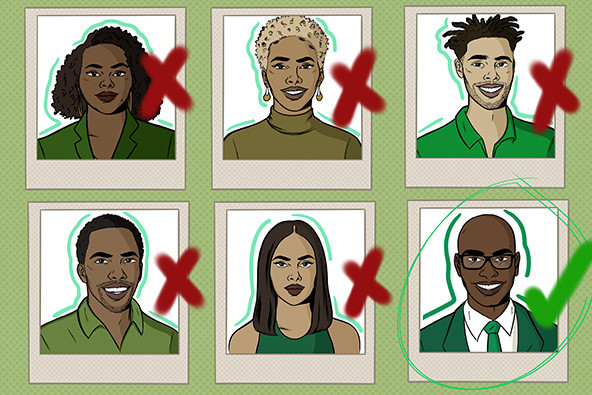

Inconsistent levels of scrutiny imposed during the hiring process creates an additional burden for individual Black candidates. A Vox article chronicles how a white male candidate was ushered to the final round of a job search alongside a Black female candidate, despite the fact that he had less relevant and fewer years of experience, graduated from a far less prestigious university, and did not have an advanced degree. She faced additional hiring requirements—more interview rounds, screenings, writing samples, references—beyond those agreed upon with the client organization. These additional steps amounted to asking the Black candidate to “prove it again” and revealed the client’s doubt regarding her qualifications; doubt not shown for the other candidate.

For many Black employees, this problematic behavior persists after being hired. A Harvard Business Review article shows this trend spans sectors and industries, where Black employees still face obstacles to advancement and are less likely than their white peers to be hired, developed, and promoted. Workplace discrimination adds stress and threatens an employee’s sense of belonging and overall well-being, and Black workers navigate a work experience that is demonstrably worse even than that of other people of color. Many face explicit racism, on the rise over the past few years, as well as subtle racism on the job. The more subtle elements include “aversive” racism (when people avoid or change their behavior around those of different races) and “modern” racism (the belief that the ability of Black people to compete in the marketplace means discrimination no longer exists, that we live in a “post racial” society). In addition, there are microaggressions—brief and commonplace verbal, behavioral, or environmental indignities, both intentional and unintentional.

Additional assumptions that can burden Black employees include being perceived as the “diversity hire.” When organizations suggest that diversity comes at the expense of quality, Black hires may feel a need to combat the belief that we are a company’s diversity good deed, and awareness of this sentiment can have a detrimental effect on Black employees’ sense of belonging and experience of the workplace.

Organizational Repercussions

The hard-to-find qualified Black candidate trope is a flavor of systemic racism that also limits an organization’s incoming workforce diversity. It is understandably challenging to attract diverse talent without an existing heterogeneous staff. When organizations cannot provide examples of employees of color contributing, flourishing, and building their careers, applicants of color are justifiably skeptical of accepting a job within them.

Organizations that ignore workplace racism empower it, which hinders an employer’s ability to be productive. Awareness of the competitive advantage of equity and diversity is rising, with many organizations regarding inclusion and diversity as critical enablers of growth. Research has demonstrated the return on investment (ROI) of racial equity. Yet, even with the business case made, lower hiring and promotion rates for Black candidates and employees persist.

Finally, it does white employees and hiring managers no favors to enable bad behavior. Overlooking racism among staff squanders a solid learning opportunity and sends the message that the behavior is condoned or, even worse, embraced. If people, Osivwemu says, “fall into the trap of thinking implicit bias is the friendly cousin of racism,” they will have dressed it up as something far more innocuous than it is. In order to show up as committed and accountable problem solvers, white employees and leadership need to see racism in the workplace as their problem, not someone else’s story with which to sympathize.

Introspection and Action

When attempting to come to terms with institutional racism, avoid simply hiring staff of color without addressing underlying issues that created a hostile office in the first place. Consider the case of the Bon Appetit test kitchen, which came under fire last summer when it was revealed that staff of color on their hugely popular YouTube channel were paid significantly less than their white colleagues—and, in some cases, not at all—for video appearances. While show producers diversified the chef lineup later that year, some were concerned that the fundamental issues like hostile workplace culture and pay inequity were not resolved.

There are no easy answers or quick fixes to address racial inequity in the workplace. It necessitates going beyond “woke-washing”—appropriating social activism language into marketing materials—or hollow gestures, to make sure efforts reflect solid commitments to explicit internal and external changes. Turn the lens inward by exploring internal policies, practices, and structures, as Demos did, when this two-decade-old public policy organization, embarked on an organization-wide racial equity transformation and published their process and lessons.

Other contextual and strategic resources include a McKinsey & Co. Race in the Workplace report published in 2021, which explores Black worker participation, representation, advancement, and a path forward, including actions companies can take. W. Kamau Bell’s United Shades of America—which the host has called Sesame Street for grown-ups—is another introspection tool. And culture commentator Jay Smooth’s TEDx talk, “How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Discussing Race,” is a great primer for broaching internal race-related conversations. He tackles the defensiveness that often accompanies these discussions via a reframe from talking about who someone is to what was said or done. He also addresses the false binary of being or not being a racist and discusses the general “goodness” of people as a practice, not a static state. Exploring multiple resources like these as a starting place is important, but so too is doing the work to chart your own path of discovery, change management, and organizational transformation.

Organizations embarking on a transformational journey can benefit from asking themselves some hard questions:

- How is your organization combating the meritocracy myth at a structural level?

- How could you dismiss the valuing of sameness and instead replace it with valuing those who can add to existing organizational culture? How can you create what writer Brené Brown calls “transformative cultures” and eliminate or emend the “culture fit” component of hiring?

- Are you willing to prioritize diversity targets in the same stringent way that a Fortune 500 company might prioritize sales goals? What is the level of accountability? Will leadership be removed if they fail to produce results?

True investment in creating a diverse and inclusive culture sometimes requires drastic changes. If your organization's make-up is 8 percent from underrepresented groups, but your aim is 30 percent, it may mean hiring exclusively from these populations until the goal is met. This could, in some cases, include members of dominant groups stepping up by stepping back. Reddit’s cofounder, Alexis Ohanian, became an example of this when he stepped down from Reddit’s board and specifically asked that the board replace him with a Black board member. “I believe resignation can actually be an act of leadership from people in power right now,” he said of his decision. Less than a week after he stepped down, Reddit named entrepreneur and Y Combinator managing director Michael Seibel as the first Black board member in the company’s history.

No one is quite sure why George Floyd’s murder, and not the murders of countless other Black people, snapped the world, even if momentarily, out of a stupor of indifference. But it’s important that leaders connect atrocities happening “out there” to what is happening within organizations, companies, and institutions. We should not squander this season of awareness, and we should recognize that this is about much more than an opening for incremental change. It is a chance to do what is indeed serious work. It’s systems-level work. And it is forever work.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Autumn McDonald.