For almost three decades, I have been writing grant proposals aimed at improving youth outcomes in school and beyond. I began with small proposals as a classroom teacher and moved to multimillion dollar proposals as a school district administrator, director of a university consortium, and now president of Search Institute, a nonprofit organization that studies and works to strengthen youth development and education.

I recently I ran into the program officer who approved one of my first major proposals. As we caught up on each other’s lives, he asked, “Given all of the grants you have written and the work you have done, what is the most important thing you would tell funders to look for when they review a proposal that involves young people?”

As I thought about his question, I realized that my answer has shifted over the years. In the first decade of my career, I would have recommended that funders review proposals for use of “best practices” and strategies that hold people accountable for using them. During the second decade, I would have said to invest in interventions that showed strong evidence of success and that used approaches such as “collective impact” and “improvement science” to scale those interventions.

Now in my third professional decade, however, I gave a simpler answer: “Invest in interventions that emphasize relationships.”

Are you enjoying this article? Read more like this, plus SSIR's full archive of content, when you subscribe.

Though he didn’t say it, I think the program officer found my answer both unsurprising and uninteresting. It’s rare to find a school, youth program, or community coalition that doesn’t say it values the relationships in young people’s lives.

But beneath the surface of that rhetorical commitment, most youth-serving organizations devote far fewer human and financial resources to building relationships with and among young people than to other aspects of their work. My colleagues and I recently interviewed 55 leaders of a diverse set of youth-serving organizations across the United States. We found that most have not defined the type of relationships they seek to build or set aside time to build them. Few collect data on relationships. And most do not explicitly include relational skills in their processes for hiring, training, and evaluating staff.

The executive vice president of a national nonprofit that works with schools captured a theme we heard during many of the interviews: “Our entire organization was founded on the principle of: ‘It’s not programs that change people, it’s relationships.’ … But I would say, because it’s almost assumed, we don’t put enough emphasis on consciously making sure that we are building those relationships … and then measuring that work.”

Many factors keep schools and programs from adequately investing in relationships, from pressure to accomplish other objectives to the challenge of connecting across the lines of race, class, and culture. Another common obstacle is the way that some funders think about (or, perhaps more accurately, don’t think about) relationships. The CEO of a nonprofit that provides disadvantaged students with workplace internships and helps them apply to college described the dynamic this way:

Some of our unsophisticated funders, they’re looking at our size and scale and saying, “Man, wouldn’t it be great if you could serve 10 times or 100 times more students? Wouldn’t it be great if all students in the school system could benefit from this learning?” And they go as far to say, “You need to put all this teaching and learning on the Internet so that students can go there virtually, read it and learn it, and go on.” And I’m like, boy, if you’re suggesting that, you have no idea how important a relationship is.

This isn’t to say that relationships are the only thing that funders should consider when reviewing proposals in education and related fields. Relationships are necessary but not sufficient for youth success. Best practices, accountability, evidence-based interventions, collective impact, improvement science, and many other ingredients are also essential. Still, as the National Scientific Council on the Developing Child concluded in an important 2004 report, “relationships are the ‘active ingredients’ of the environment’s influence on healthy human development.” Or as researchers Junlei Li and Megan Julian have argued, interventions that don’t focus on relationships are as effective as toothpaste without fluoride.

But how exactly can you build relationships with and among young people in classrooms, out-of-school-time programs, family service programs, and elsewhere? Unfortunately, there is no easy answer. To help find solutions, Search Institute in 2013 launched a multi-year program of applied research to better understand “developmental relationships”—those that help young people grow and thrive.

Our research began with analysis of the large data set that Search Institute accumulated over more than two decades of research on the developmental assets that promote positive youth development. Our studies have also included focus groups with young people and adults, and an extensive review of existing research. Through those efforts, we have identified five important aspects of developmental relationships: expressing care, challenging growth, providing support, sharing power, and expanding possibilities. Each element can be broken down into a set of discrete actions articulated in Search Institute’s new Developmental Relationships Framework:

(Chart courtesy of Search Institute)

(Chart courtesy of Search Institute)

So far, we have found that expressing care, challenging growth, and providing support happen at relatively high levels in most settings we have examined, but sharing power and expanding possibilities are much less common.

Our studies are showing that when young people experience strong relationships with parents, teachers, and others, they do better on a variety of indicators of psychological, social-emotional, academic, and behavioral well-being. Our data also suggest that the more such relationships young people have in their lives, the more likely they are to be in a position to succeed and contribute as adults. This is particularly true for young people who must overcome adverse childhood experiences such as the death, incarceration, or chronic illness of a family member. Unfortunately, we are also learning that the young people who most need these relationships are the least likely to have them.

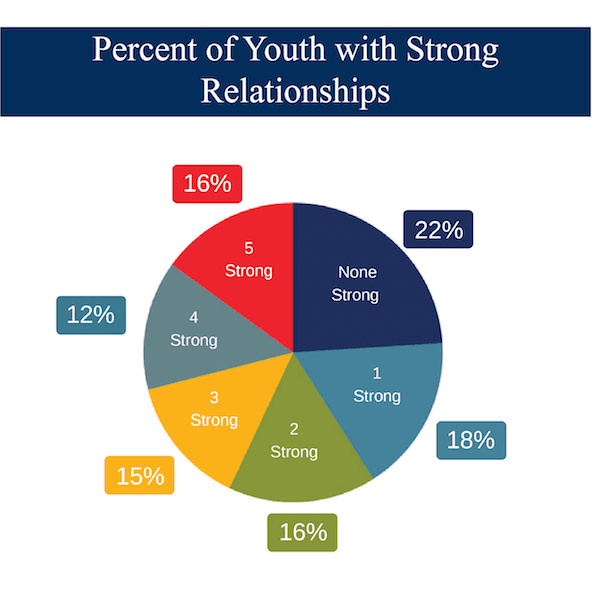

A study of 25,000 students in grades 6-12 in a diverse urban area found that some young people experience no strong developmental relationships while others experience many. (Chart courtesy of Search Institute)

A study of 25,000 students in grades 6-12 in a diverse urban area found that some young people experience no strong developmental relationships while others experience many. (Chart courtesy of Search Institute)

In the years ahead, we will evaluate and improve our Developmental Relationships Framework using multiple methods, including experimental studies of the tools and techniques we are developing to help youth-serving organizations start and strengthen developmental relationships. Those resources range from activities that help young people and adults share their sparks (deep talents and interests) to an app that maps the developmental relationships in a young person’s life.

But we don’t need to wait for experimental evidence that those tools are effective to know that we can and should work to spark the active ingredient of developmental relationships. Funders (and practitioners) can begin to do that now by asking four main questions about grant proposals:

- Does the proposal explicitly include building relationships with and among young people as a strategy for achieving its objectives?

If the answer to the first question is no, then think hard about funding (or submitting) the proposal as written. If the answer is yes, then move on to the following three questions:

- Does the proposal identify who will build relationships with young people and when and how they will do it?

- Does the budget provide resources to support building relationships?

- Does the evaluation process include collection of data on relationships, and will it be possible to link that data to project outcomes?

Answering these questions will not be simple or straightforward for many proposals, but just asking them will help those working in this arena make better decisions about what works for young people than I could during the first decades of my career.

Today it’s clear to me that developmental relationships are more than just the active ingredient in interventions that work—they are the indispensible ingredient. Fortunately, building relationships is something that educators, youth program staff, and others who work with kids deeply desire to do. Funders that help them achieve that objective will be more likely to achieve their objectives as well.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Kent Pekel.