(Illustration by Hugo Herrera)

(Illustration by Hugo Herrera)

Sometimes we lose sight of a simple truth about systems: They are made up of people. Despite all of the frameworks and tools at our disposal and all of our learning as a field of practice, purely technical, rational approaches to systems change will not make much of a dent in shifting power or altering our most deeply held beliefs. If most collective impact efforts fall short of supporting people to change in fundamentally consciousness-altering ways, then, the system they are a part of will not significantly change either.

However, over the past two decades, the prevailing view among many funders, board members, and institutional leaders has been that only quantifiable and predetermined outcomes can create impact. But if the interrelated, devastating, and deepening crises and divisions over the past two years have taught us anything, it is that complex, adaptive problems defy tidy logic models and reductive technical solutions. It is time to invest our collective energy in more relational and emergent approaches to transforming systems.

Embracing Emergence and Prioritizing Relationships

Relationships are the essence and fabric of collective impact. What’s critical for those who facilitate collective impact efforts is to support relationship development in ways that build true empathy and compassion so that authentic connections happen, particularly between diverse participants. These deeper connections can form new avenues for innovation to address the social problem at hand.

Take the work of Wesley Community Action in New Zealand. Wesley is a place-based collective impact initiative working throughout Wellington to support community-led initiatives that increase the quality and dignity of life of traditionally marginalized individuals. One of the groups Wesley works with is the Mongrel Mob, an organized street gang of predominantly Māori and Polynesian members with 30 chapters across the country. According to government census data, more of New Zealand’s prison population is affiliated with the Mogrel Mob than any other gang, and rates of substance abuse and violence are substantially higher than in the general population.

Core to Wesley’s theory of action is the belief that people are the experts in their own lives. Rather than build a three-year strategic plan with predefined outcomes to achieve the collective’s goals, Wesley Director David Hanna embraced an emergent approach to systems change and began building relational trust with members of the Mongrel Mob during planned social gatherings over many months. Staff members, gang members, and even their extended family members got to know each other through group activities in relaxed, informal settings, including a camping expedition. Through these experiences, Wesley staff and the Mongrel Mob built the relational trust necessary to transform a system that had many times failed to see the power of the lived experience.

Hanna would be the first to admit that embracing emergence creates discomfort and is not without risk. But by placing people with lived experience at the center of the collective impact effort, new ways for players in the system to work together began to emerge.

“So much of our work isn’t planned but has a relational ‘go with the heart’ feel,” Hanna said. “The connections that form release energy for new possibilities.”

For example, several wāhine (gang members’ female relatives) organized a group called the Mumzys with the goal of improving life outcomes for families. Their work led to a presentation in front of the New Zealand Parliament, and also sparked the creation of NZ P-pull, a community-led process across 24 gang chapters to help members tackle their methamphetamine addictions.

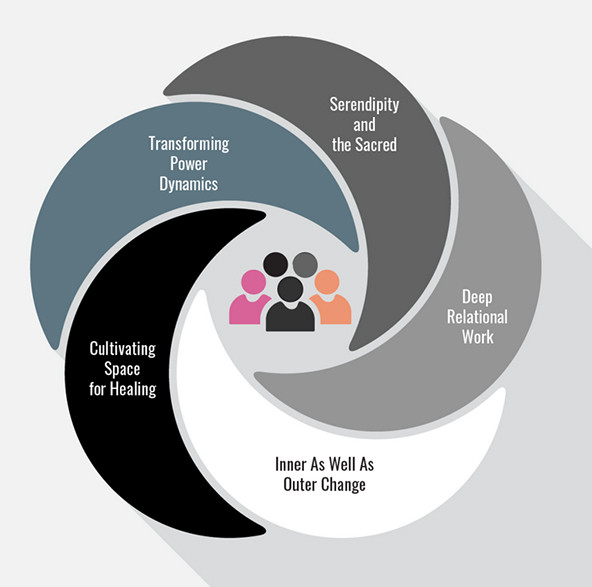

As the work of Hanna and Wesley Community Action illustrates, making meaningful progress on the complex challenges of our time requires totally different ways of working together that prioritize relational practices. Based on research and conversations with practitioners who engage in transformative change practices, particularly those stemming from nondominant cultures, these more radical and relational ways of working generally share five qualities: deep relational work, space for healing, inviting in the sacred, inner change that leads to outer change, and transforming power dynamics. In practice, these qualities never stand alone but function in interrelated ways to support the transformation of systems.

1. Deep Relational Work

Everything we know about systems tells us relationships are the core. Most collective impact leaders ascribe to the mantra: If you want to change the system, get the system in the room. As the late systems theorist Brenda Zimmerman said, “The most important unit of analysis in a system is not the part (e.g. individual, organization, or institution), it’s the relationship between the parts.”

By deep relational work, however, we mean a fundamentally different way of being in relationship. This starts with creating a space for the work that is viewed by all, especially those who do not have institutional power, as a safe environment where participants can express themselves freely and be vulnerable, connect with each other, and experience their common humanity. It is particularly important for leaders of collective change efforts to walk the talk in modelling vulnerability, and to create the conditions that encourage those in power, such as funders and board members, to do the same.

Building deep relationships with others takes time, tenacity, and a willingness to keep showing up, but the payoff is immense. When we are in deep relationship with others, we shed more of the baggage that weighs us down, share what’s in our hearts, and bring a cleaner energy to our interactions. “It is so powerful,” Hanna reflected, "that we are leaning into doing more deep relational work. We are now creating a space for conversation with opposing gangs.”

2. Cultivating Space for Healing

Unresolved, unhealed trauma is a force to be reckoned with in most, if not all, of the largest systemic issues we face. And it is far more common than we acknowledge among people involved in collective impact work.

Take the case of United for Brownsville (UB), which was created three years ago to improve the early childhood system in Brownsville, New York. Early on, UB’s cofounders David Harrington and Kassa Belay, together with Dionne Grayman, a restorative practitioner with deep local roots, recognized that being in deep relationship with parent residents means addressing collective healing from past and ongoing racial traumas. This involves acknowledging that, even though the painful or traumatic events may have occurred in the past, the felt trauma still exists in the present and will remain an impediment to future progress unless it is dealt with.

“We realized that if we're not laying the groundwork to anticipate trauma, create space for people to process their trauma, and grow into leadership amidst that trauma being relived, then we're not following through on our commitment to build capacity in a genuine way,” Belay said.

Healing circles attended by parent residents only are one such collective healing process. Funders, early childhood service providers, and even UB staff are not allowed to enter. Parents share their experiences of oppression and resilience and forge connections with each other that facilitate collective healing. Another difficult yet necessary process is mediated conversations that take place between parent residents whose families have been traumatized by early childhood service providers and representatives of those same agencies. These conversations help parents feel ready and safe when working with people in positions of power. Mediated conversations also deepen empathy among service providers and serve as an accountability mechanism for past wrongs.

3. Serendipity and the Sacred

Working together in a way that invites in the sacred and welcomes serendipity is perhaps the most difficult of the five qualities to capture on a page, in large part because people often equate words like sacred with religion or think it refers to faith-based initiatives. On the contrary, bringing the sacred into the process does not require or even assume everyone involved has a spiritual orientation.

In the collective impact context, it means setting a tone for the work that encourages everyone involved to open their hearts to enable a universal source, or grace, to enter into the work. Use of rituals, personal stories, and community narratives can help groups establish a sacred tone for their work together, as well as finding inspiration from art, silence, or contemplative practices such as meditation. While specific methods may vary depending on the local context, what unites this quality across cultures is the intent to support participants in being present to the work and to each other. It’s also about grounding the work, individually and collectively, in love.

Massachusetts-based youth organization Roca, for example, uses rituals learned from the Tagish Tlingit people in the Yukon Territories, such as burning sage, performing spoken word poetry, and passing a talking stick in the peacemaking circles they facilitate between police officers, corrections officers, and youth who are affected by urban violence. The circle “keeper” sets the sacred tone and helps participants who may view each other with hostility to let down their guard and share their stories. Sharing deeply personal stories slowly builds trusting relationships, and over time, opens people to see the whole human who they had previously reduced to a stereotype.

Roca’s approach has helped its public systems partners ground their work in forgiveness, empathy, and love. Police and corrections officers who have participated in peacemaking circles have demonstrated a willingness to change their standard policing and judicial practices, including new procedures to protect youth in dangerous situations and the introduction of support services for youth re-offenders. For example, in Hampden County, the Massachusetts local district attorney introduced the state’s first youth court that helps 18- to 24-year-old re-offenders avoid jail time by providing intensive probation supervision as an alternative.

4. Inner and Outer Change

People who work with collective impact efforts are all actors in the systems they are trying to change, and that change must begin from within. The process starts with examining biases, assumptions, and blind spots; reckoning with privilege and our role in perpetuating inequities; and creating the inner capacity to let go of being in control. But inner change is also a relational and iterative process: The individual shifts the collective, the collective shifts the individual, and on and on it goes. That interplay is what allows us to generate insight, create opportunities, and see the potential for transformation.

We can see clear examples of the interplay between inner and outer change in the system leaders and community stakeholders in New Zealand and Brownsville. In New Zealand, government stakeholders had to reckon with their assumptions and biases about the Mongrel Mob’s capacities and will for self-determination while the gang members had to begin unpacking male trauma and how it manifests in violence and drug addiction. These inner changes enabled the collective to establish more authentic dialogue between government stakeholders and gang members in their efforts to change the system. As a result, the New Zealand government and the Mongrel Mob formed a groundbreaking partnership in 2020 in which gang members act as advocates and service providers who receive government funding to address methamphetamine addiction and the crime that often results from addiction.

In Brownsville, UB’s backbone leaders’ inner work opened their hearts to more humble and authentic relationships with the community. Part of Grayman’s role as a lifelong Brownsville resident is to hold up a mirror to co-founders Harrington and Belay, who are both outsiders to the community, and ensure they remain accountable to the group’s principles of participatory planning and anti-racism. In addition, UB invests significant resources in the form of facilitated healing circles referenced earlier and personal development workshops to support inner change among parent residents and social service agency representatives. Parents have begun to claim their power and this has opened up space for power dynamics to shift and collective healing in the community to begin.

5. Transforming Power Dynamics

Collective impact efforts must be intentional about not replicating the power imbalances of the systems they work in. UB’s approach to working with the community provides an example of how to transform power dynamics through relationships. “If you're not partnering with parents in an authentic way, you're replicating a history of disempowerment and neglecting key stakeholders who have the potential to transform the work,” Harrington said. Recognizing this dynamic, UB created a family advisory board, a formal structure comprising Black and Brown residents, homeowners, individuals in the shelter system, people living in public housing, immigrants, and third-generation locals.

Hypotheses and project ideas generated in the closed-door family advisory board meetings are brought to UB’s provider action team, which is comprised of representatives from government agencies. “Early on, we talked about power dynamics and sketched out a decision-making role for the family advisory board,” Belay said. “There’s an interplay between residents and social services, but the decision-making rests with the residents first. That’s critical to address power dynamics.”

As UB has evolved over time, power dynamics are shifting in other, unexpected ways. For example, their most significant donor has now set up their own resident advisory committee as part of their decision-making process for a separate grant program.

Accessing Deep Wisdom

By calling on our sector to invest its collective energy in more relational and emergent approaches to transforming systems, we are merely naming what many of us already know: The ways we currently collaborate are simply not up to the magnitude of the task given the complexity of the social and environmental problems we are trying to solve. To get to more radical outcomes, we need more radical ways of working together. It is both as simple and as hard as that.

Those ways demand much of us as leaders and move us out of our comfort zones quickly. We must constantly remind ourselves that the process is the solution, and we must remain open to exploring new and difficult questions. What can each of us do to bring people into deep, authentic relationships with each other and create safe spaces for vulnerability? How do we design profound experiences of healing and connection to our shared humanity? How can we embrace emergence and cultivate our capacities as leaders to follow the new energy, creativity, and innovations that surface? We believe this is the next frontier of systems change. Only once we start exploring answers to these difficult questions will we begin to foster shifts in individual and collective consciousness powerful enough to transform systems.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Katherine Milligan, Juanita Zerda & John Kania.