(Illustration by Curt Merlo)

(Illustration by Curt Merlo)

The world increasingly expects and needs companies to deliver both economic and social value. Their ability to mobilize resources has surpassed even that of large governments. In the United States, for example, private-sector spending is seven times larger than governmental spending and 20 times larger than nonprofit-sector spending. With such outsize output and influence comes responsibility.

Leading business thinkers have responded by creating new models for realizing social value, such as shared value, the circular economy, Sustainable Business 2.0, and B Corporations. And investors who used to focus purely on the financial bottom line now urge companies to examine their impact on society and the environment.

The past year may have marked a turning point for many companies to accept their responsibility toward society at large and embrace it as part of their long-term strategy. In the United States, 181 CEOs of the world’s largest companies officially redefined their corporate purpose to promote an economy that “serves all Americans.” In Europe, 34 multinational companies launched the Business for Inclusive Growth (B4IG) coalition shortly after. Such announcements suggest that business must be on the right track to a sustainable and inclusive future.

But we find a different story in the track records of companies that officially pledged to contribute to the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the commitments that all UN member states made to end poverty, promote prosperity, and protect the planet by 2030. Research shows that less than half of the companies measure their impact on the SDGs. In addition, hardly any made changes to their core business activities, and only a few even changed their corporate social responsibility (CSR) efforts. If corporate commitments to the SDGs have not translated into sufficient business practices, how likely are companies to shift their entire business model based on promises?

Some scholars and practitioners specializing in inclusive growth argue that lack of progress may in fact stem not from a lack of initiatives, but from a lack of ambition. The transition to an inclusive and sustainable economy requires systemic and long-term thinking, multistakeholder collaborations, and bold and risk-tolerant capital. Companies, in the meantime, tend to invest in incremental initiatives that are close to their own value chain. To pursue loftier ambitions, companies may need a “catalyst”—a partner who can advise on the relevant social issues, identify and set ambitious goals, and develop early-stage and innovative social solutions with potential business relevance.

In Europe, a growing number of companies are seeking the support of a specific type of catalyst that we call the corporate social investor (CSI). The term refers to corporate foundations, corporate impact funds, corporate social accelerators, and social businesses that transcend traditional grantmaking and philanthropic foundations. While these vehicles are not new, their importance as catalysts for reform in the business world has emerged recently.

CSIs have a unique vantage point between the nonprofit and the business sector to identify transformative social solutions with potential business relevance. As part of the nonprofit sector, CSIs can mobilize societal stakeholders from companies, other nonprofit organizations, and governments to collaborate on shared concerns. And since they do not (or not primarily) seek financial returns, CSIs can provide the risk-tolerant and patient capital needed to incubate and test innovations (companies are more likely to invest after successful proof of concept).1

At the same time, a growing number of CSIs are exploring how their relationship with a company can serve their own social impact. In Europe, CSIs are moving from a purely philanthropic to a more entrepreneurial mindset and increasingly adopting the practices of venture philanthropy, including tailored financing (a grant, debt, equity, or a combination of those, depending on the investee’s needs), nonfinancial support (e.g., helping build a social business model), and impact measurement and management. Because some of these practices are anchored in business logic, they have helped to build mutual understanding and collaboration with the company’s practices and competencies.

In fact, CSIs have increasingly pursued alignment with the company as a strategy. For the purpose of this study, we define alignment as a mutual arrangement between a CSI and its related company, with the goal of enhancing the CSI’s social impact. The percentage of corporate foundations that have indicated that they are aligned with the business increased from 58 percent in 2013 to 76 percent in 2017.

With these trends in mind, we at the European Venture Philanthropy Association, Europe’s leading network of investors for impact and corporate social investors, asked our members why they believe that alignment has become such a growing trend among European CSIs. They responded that they expect alignment to help channel more money into social impact initiatives. Since philanthropic and governmental capital alone will not suffice to address all societal challenges, our members have embraced alignment to unlock more of the resources they need from companies.

Second, large-scale social change requires cross-sector partnerships among the public, business, and nonprofit sectors. While many CSIs have traditionally operated at arm’s length from business interests, they now recognize how alignment can help to mobilize companies for collective impact.

Lastly, practitioners trust the effectiveness of alignment. Published research on the topic has been overwhelmingly positive and has highlighted its ability to unleash new resources and ideas for greater social impact.2

The Basis of Alignment

Even though many CSIs see the potential of alignment, they have no consensus on what basis they and their related companies can align. Some CSIs interpret alignment as a link with core competencies, while others see a link with the core business, the business strategy, or even marketing power. Even during our initial conversations with 38 senior executives of CSIs, we could find no agreement on what alignment is or how to pursue it.

The research literature oversimplifies alignment as a uniform and self-explanatory concept. It does not recognize the variety of alignment strategies that CSIs and their related companies seek. We cannot take for granted that any type of alignment results in the same benefits. We must instead explore the nuances and potential drawbacks of different kinds of alignment.

CSIs that do not understand the potential challenges of alignment risk losing their social license to operate.3 Legally and ethically, they need to ensure that alignment does not create business benefits at the expense of social impact. For example, the Foundation for a Smoke-Free World, initially funded by tobacco manufacturer Philip Morris International, has been criticized by the World Health Organization and in The Lancet for its lack of independence from the tobacco industry.

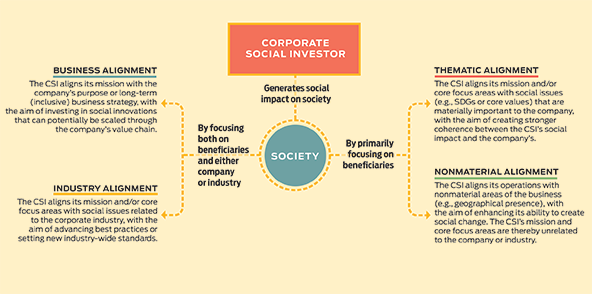

Given the far-reaching pursuit of alignment, we must enhance our understanding of the concept, its benefits, and its challenges. Otherwise, CSIs and companies might chase a management fad at the expense of their social impact. To help inform their decision-making, we conducted a qualitative study with 45 practitioners, including (executive) directors of CSIs, senior managers from companies, and experts on corporate social investing and inclusive business strategies. Our analysis of the results shows that four different ways of aligning exist, each with inherent benefits and consequences for the pursuit of social impact. They are business alignment, industry alignment, thematic alignment, and nonmaterial alignment. Let us review the four types and examples from European CSIs.

Business Alignment

The first type of alignment, business alignment, is pursued by CSIs that aspire to have a direct positive influence on the company’s social and environmental business practices. CSIs do so by aligning their mission with the company’s purpose or long-term (inclusive) business strategy and investing in social innovations that can potentially be scaled through the company’s value chain but that transcend the company’s current business interest.

What my team gets tasked with is being at the vanguard of pushing further ahead in the areas where the commercial business is not looking.

Renault Group, the international car manufacturer, provides an example. In 2011, it founded Renault Mobilize, a social impact fund dedicated to developing inclusive and social businesses that give disadvantaged people access to mobility. This fund is completely aligned with the company’s long-term, inclusive business strategy of “providing sustainable mobility to all around the world.”

“As a social business, we sell mobility solutions at a low cost to people who really deserve and need a solution to find a job or to keep a job,” says François Rouvier, the director of the Mobilize program. “This is our primary mission. Our secondary mission is to change the company. I believe that we have a very strong responsibility toward society. A way to exert this responsibility is to roll out social business throughout the company wherever Renault is present in the world.”

Business alignment can enhance the social impact that the CSI delivers, directly or via the company, in three ways. First, CSIs and companies can work together to identify and scale solutions whereby the CSI serves as incubator and the company as an accelerator. Since CSIs are closer to social challenges and beneficiaries, they are better equipped to spot truly innovative and revolutionary social solutions, while companies are better at accelerating the impact of such solutions by integrating them into their value chain. Most companies are too limited by short-term pressures to recognize the potential long-term impact of disruptive social innovations and too risk-averse to invest before successful proof of concept.

“What my team gets tasked with is being at the vanguard of pushing further ahead in the areas where the commercial business is not looking,” says Sam Salisbury, former director of the Innovation Lab at Centrica Innovations. Founded by multinational energy company Centrica in 2017, the £100 million ($125 million) fund Centrica Innovations supports cutting-edge technologies related to the company’s core business of energy and electricity. If CSIs like Centrica Innovations can incubate social innovations until they can demonstrate their business relevance, companies are more likely to understand their potential and ideally integrate them into their value chain. This strategy creates vast opportunities for social impact at scale.

Second, such business alignment can enable the CSI to tap into the expertise and know-how of the company and its entire value chain. The CSI and its investees can use the company’s relationship with suppliers or manufacturers and its access to market expertise, technology, and innovations to pursue its goals. Renault Mobilize, for example, was able to support its investee Garage Solidaire with products from the company. Garage Solidaire is an inclusive business that offers car repair services at an affordable price to vulnerable people in need. Through the link with the car company, Renault Mobilize supports Garage Solidaire with Renault spare parts at the mere cost of production, enabling the enterprise to offer its services at a much lower price to beneficiaries.

Third, business alignment can help CSIs challenge and inspire companies to uphold their inclusive and sustainable business efforts. Take the example of the Danone Ecosystem Fund, which supports inclusive business solutions that address societal challenges related to French food-product company Danone’s value chain. Its subsidiaries and local nonprofit partners co-develop inclusive business models that empower vulnerable stakeholders, such as farmers, caregivers, or waste pickers. “At the beginning, the role of the ecosystem fund was to engage the maximum number of business units into this new equation: the inclusive economy,” says Jean-Christophe Laugée, former vice president of nature and cycles sustainability at Danone Ecosystem. “But over time, the perspective on the ecosystem and the topics we’ve been addressing contributed to the design of the new strategic agenda of the company.” Danone set for itself the goal of nourishing and protecting people and the planet under the vision of “One planet. One health.” The Danone Ecosystem Fund and other corporate impact funds are thereby important to pioneer new ways for the associated business to be more inclusive and achieve prosocial goals.

Despite business alignment’s potential for positive social change, the strategy also poses some challenges. First, in order to use this type of alignment effectively, both the company and the CSI must commit authentically to advancing social impact. If social impact and business interest conflict (e.g., when the company operates in a contested industry, such as mining or gambling), or when the company still pursues “business as usual,” this alignment type will not unlock its potential for social impact and may even jeopardize the CSI’s legitimacy. At the same time, neither the CSI nor the company should consider business alignment a substitute for the company’s sustainability strategy. The CSI should contribute distinct, additional, and complementary societal value that goes beyond mere commercial interests.

Because business alignment can bring the CSI’s activities relatively close to the company’s value chain, not every CSI can pursue such alignment. Most national laws legally restrict corporate foundations from business alignment, because their charitable status does not allow them to serve the interests of the company, directly or indirectly. Corporate foundations should therefore operate with caution and carefully assess the regulatory environment before pursuing business alignment. Other legal structures, such as a corporate impact fund, social accelerator, or social business, are therefore set up to pursue business alignment. Over the past couple of years, we have seen many of these vehicles emerging in Europe. For example, CSI Fundación Repsol, connected to Spanish energy company Repsol, launched a new social impact investing fund supporting precommercial entrepreneurs in the field of sustainable energy transition. And MAN, the European commercial bus and truck manufacturer, set up an impact accelerator supporting social entrepreneurs working on mobility, including transportation and logistics.

Lastly, CSIs that pursue business alignment may feel confined to solutions that promise only limited impact. CSIs that screen for business relevance may be drawn to cheap, easy solutions that do not address the most vulnerable people or the most complex social challenges. Here, CSIs may need to compromise. Sam Salisbury, for example, saw this decision as a trade-off he was willing to make. “In the past, we were making impact investments quite freely, without having to think too much about strategic alignment,” he says. “One of the opportunities we have now is that the resources I can put behind a problem are far greater. So the trade-off that we made was that we brought it [Centrica Innovations] closer to the commercial interest of Centrica, but we think that this allowed us to put more resources into solving a social problem. Part of our role is identifying the problems that are worth solving.”

Industry Alignment

In the second type of alignment, CSIs aspire to tackle a social challenge related to an entire industry. They align their mission or core focus areas with social issues of special concern in the industry to advance best practices or set new industry-wide standards. They often do so in close collaboration with other industry actors.

The C&A Foundation, the philanthropic arm of the international fashion retailer C&A, defines itself as “a corporate foundation [that is] here to transform the fashion industry.” 4 One of the major issues it has identified in the industry is its large environmental footprint. Although the problem is widely known, the industry has not taken significant steps to address it. The foundation therefore decided to create a collaborative platform, Fashion for Good, that helps companies spot innovations that can transform how the industry works. Through this and other initiatives, the foundation has been pushing for industry-wide changes in the materials it uses (moving from unsustainable to sustainable fiber) and the treatment of its workers.

By pursuing industry alignment, CSIs can seize upon three advantages. First, since the CSI pursuing this strategy focuses on creating change within an entire industry, it is naturally drawn toward thinking systemically—about which actors and initiatives are needed to foster change across the sector. CSIs thereby benefit from the fact that they are not bound by competition and can seek the support of stakeholders that a company would usually not consider.

The progress toward changing the apparel industry’s modus operandi was very slow, according to Leslie Johnston, executive director of C&A Foundation. “We noticed that many companies tend to keep their innovations close to their chest, as they often can offer a competitive advantage or a way to differentiate in the market,” she says. “And while we know that the industry needs to embrace circular business models, it’s difficult to do that in a vacuum; it requires a collaborative approach.” For these reasons, the foundation launched Fashion for Good. While C&A was its first brand partner, Adidas, Zalando, and other large industry players also joined the initiative. So the affiliated business is just one of many relevant stakeholders a CSI engages to transform the industry, but the support of that business can be essential to influencing other businesses in the industry to join the effort.

Second, the CSI that pursues industry alignment can use the company’s industry-specific assets—its knowledge, expertise, networks, and other tangible resources—since the contexts in which both operate have clear synergies. Take, for example, the Syngenta Foundation for Sustainable Agriculture (SFSA), whose mission is to improve smallholder farmers’ livelihoods in Africa and Asia. The foundation helps to accelerate the development of affordable drought-tolerant crop varieties in dry regions. To develop such crops, the foundation can build on the vast expertise of Syngenta, a global agriculture company and seed producer, to complement the insights of research institutions and local seed producers. In some cases, the foundation can even use Syngenta’s technology to boost its support to beneficiaries, for instance, by helping to raise the yields of noncommercial crops, such as cassava and teff, or by improving the nutritional value of crops for local populations in low-income countries.

Third, working on industry-wide challenges enables CSIs to nudge industry players to set higher standards for their own operations and be more inclusive about who they serve. For Rebecca Hubert-Scherler, legal counsel at Syngenta Foundation for Sustainable Agriculture, it means alerting the industry to the needs and problems of small farmers. “We want to raise awareness of the bottlenecks faced by rural smallholder farmers and encourage or pull the company [Syngenta] and other seed companies to adapt their technologies and adopt practices that can better serve these smallholder farmers,” she says. Besides companies, the foundation also raises awareness of smallholder farmers’ issues among governments, research institutions, and nonprofits. By drawing attention to neglected stakeholders or issues and developing new best practices and social innovations, these CSIs can pave the way for front-running companies to further develop their inclusive business approaches and thereby raise the ambition for the entire industry.

As with business alignment, the credibility of industry alignment requires the company to be fully committed to sustainable and inclusive industry standards. If the company does not do so authentically, the public will not perceive the CSI’s efforts as authentic either. Advanced companies will moreover be able to recognize the long-term value of the CSI’s work, even if it can be disruptive. A CSI may have to walk a fine line between raising the industry’s sustainability standards and disrupting the business of its affiliated company. For instance, what if a certain social innovation can improve the industry’s social or ecological footprint but will challenge the business in the short term? If the company is not able to recognize the long-term benefits of improving the industry’s sustainability standards, for society and for its own long-term viability, it might reduce or even end its support to the CSI. We find that companies appreciative of industry alignment are typically front-runners, recognizing that an ever-rising sustainability bar will make it more difficult for laggards to remain competitive.

Given the interdependence between the CSI’s industry-wide social mission and the company’s sustainability strategy, a CSI should have a well-balanced governance structure in place, representing senior executives of both sides, as well as independent directors, to constantly monitor the credibility and alignment of both aspirations. In addition, practitioners recommend formalizing the relationship with the company through a memorandum of understanding or a code of conduct to clarify, both internally and externally, the boundaries of collaboration.

Thematic Alignment

Within the third type of alignment, thematic, CSIs align their mission and/or core focus areas with social issues that are materially important to the company (e.g., water scarcity is a material issue for beverage producers). At the same time, the CSIs differentiate themselves from the company by addressing neglected beneficiary groups, issues, or geographical areas that are beyond the (immediate) interests of the company. They seek thematic alignment as a means to connect with employees of the company and call attention to societal challenges that exist beyond their business perspective.

Take Trafigura Foundation, founded by global commodity trader Trafigura, which defined its mission to provide long-term funding and expertise to vulnerable communities around the world to improve their socioeconomic conditions. Its secondary objective, according to Trafigura Foundation Executive Director Vincent Faber, is to change employees’ worldviews.

“It is my personal conviction that besides the philanthropic work we do, making the world a better place, it is the purpose of a corporate foundation to have an educational role within the company,” he says. “I want to be an eye opener for corporate employees about social issues that are out there, in whatever type of society the business operates, beyond looking at markets and products. I want to sensitize the people and make them more aware about the human reality.”

Since 2015, Trafigura Foundation has focused on two themes that are also of material interest to the related company and thus affect employees and corporate decision makers: first, fair and sustainable employment, and second, clean and safe supply chains.

CSIs keep moral initiatives on the company's radar—even when companies look primarily for the business case of their initiatives.

Thematic alignment provides three advantages to the CSI, directly or via the company. First, it enables the company and the CSI to complement each other’s distinct approaches, exchange knowledge, and build on each other’s expertise and experience. As a result, they can jointly support a larger scope of initiatives surrounding the theme and use their collective insights to address those issues more deeply and effectively. “By working on similar themes, the foundation can build bridges with CSR and tap into their expertise,” Faber says. “We are also able to make connections between our NGO partners and experts from the company, which helped our NGO partners to develop better and more relevant solutions that were built on the practices and insights of the company. But we also noticed that the company started to reflect more on [its] role within the larger ecosystem and established more sustainable practices.”

Second, thematic alignment enables CSIs to show employees that commercial initiatives can complement social initiatives (but not replace them). It can help build awareness about existing societal challenges, the importance of morality and philanthropy, and alternative perspectives on the company’s larger role in society. In the long term, these efforts can help shape employees’ moral compass, both on the job and in their private lives.

“We want employees from the bank to participate in our programs so they learn about what is happening in society and [understand] that there is another part of society that you need to take into account as well,” says Pim Mol, managing director of the Rabo Foundation, which helps vulnerable people to become self-sufficient, particularly smallholder farmers in emerging economies. The foundation thereby aligns with a theme deeply rooted in the history and business model of the related Rabobank, a Dutch cooperative bank founded for and by farmers. “It’s about being a kind of societal mirror or Trojan horse, so employees take social and ecological key performance indicators back into the bank,” Mol says.

Third, CSIs keep moral initiatives on the company’s radar—even when companies look primarily for the business case of their sustainability initiatives. Sustained attention to moral initiatives can institutionalize appreciation and support for social impact, even if they have no direct business value. Ultimately, the company might start investing in new moral initiatives as well.

In this type of alignment, both the company and the CSI have clear and separate interests: commercial and societal. This division makes thematic alignment suitable even for corporate foundations that operate under strict legal constraints. The CSI’s social legitimacy is strong and less vulnerable to criticism, because it operates at arm’s length from the company and is focused solely on impact. The CSI can pursue its thematic goals even when the related company has not (yet) progressed on its own sustainability and inclusive business initiatives or operates in a contested industry, like gambling or mining.

However, thematic alignment also involves some challenges and risks. The CSI’s ability to keep the company’s interest can depend heavily on the company’s readiness and willingness. For example, if business executives have little appetite to incorporate a more socially oriented mindset, the CSI can end up as something “nice to have,” with little influence on the corporation or its employees.

In addition, pressing social issues that the CSI identifies may go unaddressed when they have little relation to the business interests or themes of the company. Multinational companies that focus on globally relevant themes may have no interest in local or regional social issues. If the company leads or unduly influences the thematic agenda, the CSI may ignore worthwhile causes or abandon them long before it can actually demonstrate impact.

Nonmaterial Alignment

We identified the fourth type of alignment, nonmaterial, among CSIs that have a strong focus on exclusively pursuing social impact. These CSIs either do not aspire to generate any change in related companies or are not at liberty to do so (e.g., because of a strict formulation of their mission in their bylaws). While such circumstances may suggest that no alignment is the only choice, CSIs can in fact still benefit from seeking nonmaterial alignment. In this case, CSIs align their operations with nonmaterial areas of the business, such as its geographical presence or its business network. The CSI pursues this type of alignment to enhance its ability to use corporate assets (e.g., employees or company relations) to operate more effectively. The CSI does not have to align its mission and core focus areas with the company.

For example, the JTI Foundation was founded in 2001 to help the underprivileged and victims of natural or man-made disasters improve their quality of life. The foundation’s mission and focus areas are unrelated to the affiliated company, Japan Tobacco International, which operates in approximately 70 countries. However, as JTI Foundation Managing Director Stefan Rissi explains, the foundation seeks nonmaterial alignment with the business on geography: “Our purpose is to help victims of disaster worldwide. We can in principle go global, but we can obviously not cover the whole planet. … Therefore, we are present only where the company is present. This enables us to get access to reliable information, which is critical to providing effective help in postdisaster contexts.”

Corporate representatives expressed pride in having a foundation that invests in social projects, simply because it's the right thing to do.

Nonmaterial alignment can enhance the CSI’s social impact, directly or via the company, in three ways. First, nonmaterial alignment affords CSIs the freedom to operate and generate impact where they feel it is needed most; they need not restrict themselves to (potentially) business-relevant issues. After all, not all social issues have, or ever will have, direct business relevance, but that doesn’t diminish their importance for society and communities. The Lloyds Bank Foundation for England and Wales, for example, aligns on Lloyds Banking Group’s broader purpose to help Great Britain prosper but focuses specifically on underlying social issues that small and local charities address, such as homelessness, domestic abuse, and mental health. The foundation tackles these challenges and supports communities in ways beyond the bank’s business scope.

Second, even if the CSI’s mission is unrelated to the company, the CSI is likely to benefit from nonmaterial company assets (e.g., phones or trucks), expertise (e.g., local-language skills or accountancy), or connections (e.g., access to partners or distribution channels). Through nonmaterial alignment, the CSI has a loyal partner it can rely on.

Rissi gave us an example of how nonmaterial alignment boosted the JTI Foundation’s impact: “During the 2013 flash flooding in Sudan, many NGOs, as well as governmental aid agencies, were not allowed to enter the area to provide first aid to the people. But the foundation works with a small emergency relief agency that we managed to get into the country and thus provide immediate emergency relief, because of the strong position of the company in the country. With the help of the company, we were able to get the government’s authorization for this NGO to intervene and help, while most other charitable organizations were not able to do so.”

Third, nonmaterial alignment can alert the business to social issues long before they would otherwise attract the company’s attention. Here, CSIs spot important trends in society that might affect the business over time. Lloyds Bank, for example, has long-standing ties to local communities and is aware of the complex social issues British citizens face, but believes the foundation, not the bank, is most suited to address them. However, after the Lloyds Bank Foundation of England and Wales highlighted how domestic abuse, one of the foundation’s focus areas, also affects many Lloyds customers, the bank took action itself and set up a Domestic and Financial Abuse Team. This unit now helps affected customers and employees through special financial guidance and introduces them to NGOs that can provide further emotional and practical support.

Few to no restrictions on CSIs pursuing this type of alignment exist, where the CSIs’ sole focus on social impact is evident. Even corporate shareholder foundations, such as the IKEA Foundation or the Robert Bosch Foundation, or CSIs operating under strict fiscal regulations can seek nonmaterial alignment without placing their social legitimacy at risk. The CSI can clearly demonstrate and articulate the impact of such alignment independently from the company’s activities.

CSIs often use moral and value-based arguments when seeking nonmaterial alignment with a company. This concept may seem counterintuitive to those who believe that appealing to the business case only (e.g., enhancing brand equity or customer loyalty) will attract the company’s top management’s attention. But we found that corporate representatives expressed pride in having a foundation that invests in social projects, simply because they felt it’s the right thing to do. CSIs, therefore, should not shy away from reaching out to top company executives and managers and making the moral case to secure the company’s long-term support.

The downside of nonmaterial alignment is that the CSI’s social impact remains confined to its own operations, using little of the company’s capabilities to create and scale social impact. The business, as a result, will not benefit from the CSI’s unique ability to influence it toward more sustainable and inclusive practices. And the CSI, in turn, will not benefit to its fullest potential from the business’s assets and resources, which could otherwise further its impact.

The Benefits of Typology

We believe that this alignment typology will help practitioners better structure and understand corporate social investing by recognizing the similarities and differences among CSIs. This understanding, in turn, will enable them to have a more nuanced discussion about alignment and their strategic approach and to reflect on their own positioning within the sector. Besides defining their current alignment type, practitioners can evaluate whether this position matches their goals and aspirations or whether another alignment type might be more favorable. In addition, executives of CSIs can more easily identify peers with similar alignment types and engage in meaningful discussions about their particular challenges and opportunities.

The typology is not static; CSIs can transition between different alignment types if they aspire to do so. Nor are the alignment types mutually exclusive; some CSIs pursue a secondary type of alignment. For example, while C&A Foundation primarily pursues industry alignment, it also decided to align one of its focus areas with a theme that resonates particularly with the company, rather than with the industry at large: “building strong communities in regions where C&A operates.” The foundation thereby seeks primarily industry alignment, complemented by a touch of thematic alignment.

Finally, this typology can offer corporate executives a different perspective on achieving social impact by combining market-based and nonmarket-based strategies. In this regard, European companies have started to develop multiple organizational structures to support complementary impact strategies. Schneider Electric, for instance, founded a corporate foundation, an NGO, and three impact funds, each serving different yet complementary purposes toward its mission of providing energy access to all. The foundation works exclusively with nonprofits and focuses specifically on providing vocational training. The NGO concentrates on offering nonfinancial support through corporate volunteering programs. The three impact funds support innovative energy technologies from France and Europe to sub-Saharan Africa and South and Southeast Asia. Schneider Electric recognizes that each vehicle has its unique potential, and the company will continue to rely on its CSIs to spot innovative and bold solutions. By combining different impact structures and alignment types, CSIs and their affiliated companies can enhance the scope and scale of the collective social impact they generate.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Karoline Heitmann, Lonneke Roza, Priscilla Boiardi & Steven Serneels.