(Illustration by George Bates)

(Illustration by George Bates)

Accidental death and dismemberment insurance” just might be the most grisly consumer product name in history—the name suggests that if you think you need this insurance, what you might actually need is a dramatic change in your lifestyle or occupation. Two years ago, when I embarked on a research study to understand why some civic organizations grow to be large and influential while others don’t, little did I know that accidental death and dismemberment insurance would provide the answer.

But there I was, perusing the member benefits of the National Rifle Association of America (NRA), when I was surprised to discover that one of the reasons people join is that the NRA will automatically insure you (and your limbs) in case of a firearms accident. This morbid, but surprisingly attractive, member benefit turned out to be the key that unlocked for me the secret of scale: the core model for growth that every large-scale civic organization shares.

What I found is that the largest civic organizations have all scaled up using the same basic approach—a model I call “functional organizing.” All of these organizations provide benefits and services to cater to the everyday needs of their members—such as insurance, childcare, support groups, and discount cards—giving people a practical reason to join and remain active while providing the organization with a steady revenue stream. With more than four million members and a robust $250 million budget, the NRA and its package of member benefits perfectly illustrate the secret of scale.

The Quest for Scale

I began searching for the secret of scale after seven years of running the Center for Progressive Leadership, a national training institute for leaders of civic organizations. Over that time, our institute trained and coached leaders at more than 1,000 civic organizations, ranging from local community centers to state-level advocacy groups to national issue organizations.

Although civic organizations work on an array of issues, they share a focus on engaging citizens in creating systemic change, spurring fundamental shifts in culture, policy, and politics. Civic organizations see citizens not only as recipients of services but also as social-change agents themselves. The social-change efforts can be as simple as neighborhood residents coming together to create a community garden or as ambitious as advancing a national policy agenda for education reform.

Many are traditional membership organizations, such as the NRA, AARP, and AAA. But others, such as Planned Parenthood, local immigrant organizations, and lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) community centers, provide services for millions of community members who are not officially “members.” Civic organizations include unions and worker organizations, neighborhood associations, community service clubs, PTAs, business and professional associations, and co-ops. Civic organizations also include churches, which often endorse a range of social transformation goals in addition to their mission of personal transformation. Whatever the form or goal of these civic organizations, they share the core underlying idea that citizens have the power to reshape our society.

Civic organizations across the United States struggle with a common fundamental problem: they simply aren’t growing to the scale needed to create systemic change. For me, “growing to scale” happens when a civic organization both builds deep relationships with a significant portion of the people in its community (measured by frequency of interactions and ability to influence members) and develops a robust, sustainable financial base (measured by percentage of revenue that is self-generated).

Most civic organizations struggle to reach beyond the same core group of activists to more deeply engage members who are often little more than names on mailing lists. Instead of developing a broad donor and revenue base, many civic organizations have become overly-dependent on big grants from foundations, large donors, and government—grants that are shrinking in the wake of the financial crisis and government cuts.

I knew there must be a better model. So with the support of a fellowship from the Tides Foundation, I launched a research project. I first looked at every large-scale civic organization I could find, ranging from US institutions such as the NRA, AARP, megachurches, unions, and trade associations to international organizations such as the Canadian Federation of Students, the Mondragon workers cooperative in Spain, and consumer cooperatives in England. I also looked at local US organizations that have achieved significant scale within their regions, such as CASA de Maryland and Make the Road New York.

In the end, I focused my research on the organizing, membership, and business models of more than 50 large-scale membership civic organizations. I dug into these organizations’ finances, studied their membership models, assessed their policy and organizing strategies, and gained an understanding of what drives their growth and power. It was through this process that I discovered the NRA’s member benefits package, including its accidental death and dismemberment insurance.

How The NRA Scaled Up

With convincing victories in gun control battles in Congress and state legislatures across the country, the NRA has proven yet again that it is one of the most powerful civic organizations in the country. How exactly has the NRA grown to a scale that permits it to dominate the political landscape on gun control issues?

Many assume that gun owners join the NRA for the same reasons people join pro-choice organizations or environmental organizations: to show their support for a cause they believe in. In reality, most people join the NRA because the member benefits fit their lifestyle. They join to get access to their local hunting clubs, shooting and safety classes, kid and family programs, gun insurance, free subscriptions to the NRA’s magazines, discounts at thousands of gun, sports, and outfitter shops, and, yes, accidental death and dismemberment insurance. The NRA’s American Rifleman is one of the 50 most widely read magazines in the country, and American Hunter is in the top 100. Moreover, between the NRA’s discounts and free insurance, the $35 a year membership quickly pays for itself for active gun owners.

The NRA’s services and programs have made the organization a trusted brand with its members. Building on these relationships, the NRA activates its members for advocacy and civic engagement. Through its local clubs and “Activist Centers” (often hosted by gun shops), the NRA carefully shepherds members into deeper and deeper engagement as volunteers and activists for the organization. This active member base, coupled with heavy political spending, places the NRA among the most powerful lobbying forces in the United States.

The NRA’s member services and benefits are also the backbone of the organization’s financial success. In addition to the more than $100 million a year that members pay in dues, the NRA brings in more than $30 million from businesses that pay to be part of the NRA’s discount network, advertise in its magazines, and receive product endorsements. Altogether, the NRA generates two-thirds of its total income from dues and earned revenue.

The NRA’s benefits and services make the organization relevant to the daily lives of its members. This is the true secret of scale: offering benefits and services that build deep and lasting relationships with members, and then activating those members for long-term, systemic change goals. This is the key to effective functional organizing.

The Power of Functional Organizing

Functional organizing enables the NRA to build a deeply engaged membership and robust financial foundation to advance gun rights. The NRA capitalizes on its local gun clubs, political action centers, and popular magazines to draw members into fights against gun control legislation—fights that the NRA has won over and over again.

The NRA is hardly alone in using functional organizing to attract members and build a financial base through benefits and services. In fact, every large-scale US membership organization is fueled by functional organizing.

- Almost 40 million seniors receive discounts, insurance, travel advice, and financial services from AARP. AARP The Magazine is the largest circulation magazine in the United States, giving the organization a powerful voice for influencing seniors and protecting their interests on issues such as Medicare and Social Security.

- Approximately 15 million US workers belong to unions that negotiate better wages, benefits, and working conditions for their members. Unions then build on these workplace relationships to activate members for policy and political campaigns relevant to working families.

- Each year, through nearly 800 health centers across the country, Planned Parenthood provides reproductive health services and education to 5 million women. These functional health services fuel Planned Parenthood’s $1 billion annual budget and have enabled the organization to attract more than 6 million members and supporters. With a strong financial base and deep connection with women across the country, Planned Parenthood is a powerful lobbying force for reproductive rights and women’s health.

- About 150 million Americans attend church regularly, not only to connect to spiritual communities, but also to access services ranging from childcare and summer camps to business classes and financial planning support. Churches have used their deep member relationships to spearhead social movements ranging from civil rights and anti-war campaigns to the early temperance movement and the modern conservative social movement.

- More than 50 million Americans belong to AAA in order to access emergency road service and discounts. AAA is one of the most active lobbyists for automobile and transportation spending and regulations at both state and national levels.

- The top 10 professional associations, such as the American Bar Association and the National Association of Realtors, average more than 300,000 dues-paying members who gain access to accreditation, training, news, conferences, and professional networks. These professional associations regularly activate their members on advocacy campaigns for policy priorities affecting their sectors.

Large-scale membership organizations have all developed a set of benefits and services that are relevant to the daily lives of their members. These benefits and services attract new members, keep old members engaged, and most important, build member relationships that the organization can activate for social and policy change initiatives.

The beauty of this model is that through services and benefits, functional organizations also create robust revenue models. Successful functional organizations develop their member services and benefits into high-growth businesses, which, in turn, finance these organizations’ operations and growth.

The Trap of Issue Organizing

When I began this research, I assumed that many of the most recognizable issue advocacy organizations—like the American Civil Liberties Union, Greenpeace, NARAL Pro-Choice America, Amnesty International, and the National Right to Life Committee—would rank among the largest civic organizations in the country. But no issue organization comes close to matching the scale of the largest functional organizations.

Although issue organizations often play an important role in advancing focused policy agendas, they are inherently limited in scope and scale. They do not offer the kinds of services and benefits that functional organizations do. Rather, issue organizations start with the assumption that caring about an issue is enough to motivate someone to become a member or make a donation.

But most Americans don’t view themselves primarily as activists. As a result, issue organizations rarely grow to engage more than a few hundred thousand members. They struggle to build independent donor and revenue bases, instead becoming highly dependent on foundations and large donors. The top five issue groups combined have fewer members than the NRA alone. They are an even smaller fraction of the membership of AARP or the largest churches. (See “Comparing Functional and Issue Organizations,” below.)

Despite the limitations of the issue organization model, it has, since the 1960s, become the dominant model for civic organizations. There are a slew of groups organizing around every issue imaginable, from poverty and hunger to animal rights and the environment to reproductive rights and abortion to education reform and child development.

Although limited in scale, many smaller issue groups have been able to create outsized policy and political impact, using strategic deployment of activists and smart media strategies. And conversely, although scale creates opportunities for impact, the largest functional organizations often fall short of creating lasting social change.

Nonetheless, scaled membership and finances do create a powerful platform for advancing systemic change. The NRA and AARP have been at the center of two of the biggest policy fights in recent years: gun control and national health care. With vital services and benefits that are highly relevant to their members’ everyday lives, functional organizations have the tools to develop deep and lasting relationships with millions of Americans. These deep member relationships are the crux of functional organizations’ power to advance cultural, policy, and political change.

Engaging Members

One might think that having millions of members would make it difficult for organizations to sustain deep relationships. It turns out, however, that members of functional organizations often access benefits, services, and information weekly or monthly. In contrast, members of many issue organizations rarely interact with the organization more than two or three times a year.

This significant disparity reflects starkly divergent approaches to member engagement. Issue organizations constantly ask, “How can we get this member more engaged in our issues?” whereas functional organizations constantly ask, “How can we get more engaged in this member’s daily life?”

Megachurches provide a good example of the member-focused approach. The fastest-growing megachurches have moved far beyond Sunday services. They now provide after-school programs, business and financial literacy classes, and a stunning array of support groups for everything from single parenting and married life to hiking and fitness to music and arts.

The deep member connections that megachurches, the NRA, and other functional organizations develop are critical for their success. Engaging members in fundraising, volunteering, events, programs, and issue campaigns is predicated on having trusted bonds.

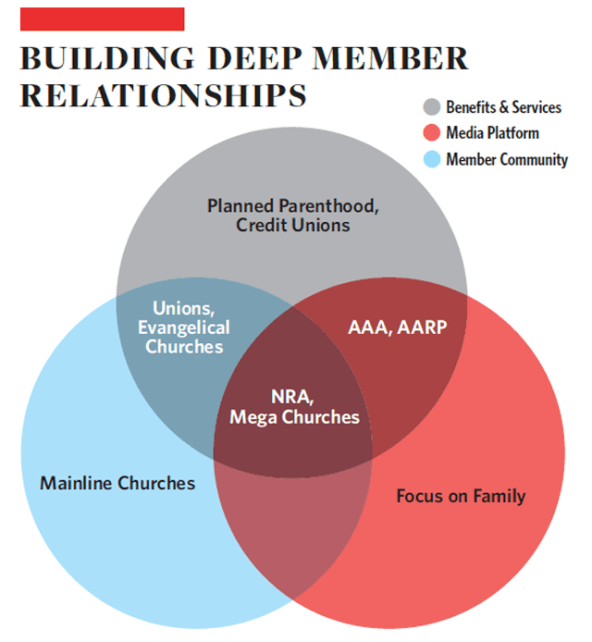

The organizations use three core strategies for building deep relationships with members: 1) They provide tangible benefits and services, 2) they foster in-person member communities, and 3) they create engaging media platforms. Some functional organizations, such as the NRA, employ all three of these strategies to engage members, but most use only one or two. (See “Building Deep Member Relationships,” below.)

Provide Tangible Benefits and Services | Benefits are often the initial impetus for members to join civic organizations, whether those benefits are AARP’s discounts, the financial services of credit unions, the YMCA’s gym membership, or AAA’s road service. Not all benefits, however, are created equal when it comes to building deep member relationships. Monetary benefits and transactional services are helpful for members and generate needed income for the organization, but they are rarely enough to develop and sustain a trusted relationship. Building trust requires more intimate and consistent engagement with members.

Member services that involve a direct personal relationship between the organization and its members—such as business classes at megachurches, health services at Planned Parenthood, or legal services provided by unions—have greater potential for building trusted relationships than purely transactional benefits do. These relational services create space for sharing information about important issues and for encouraging members to take action in the organization’s initiatives.

Some of the most striking examples of institutions with deep member relationships are LGBT community and health centers across the country. These organizations have had to take a functional organizing approach to help their members overcome the discrimination and legal barriers that LGBT people face.

The San Francisco LGBT Community Center (the Center) is one of the largest LGBT-serving organizations in the country, and it is a good reminder that organizations can grow to large scale in a single community. More than 9,000 people visit the Center every month for a wide array of services, including career counseling, small business lending circles, youth programs, childcare, and first-time homebuyer programs. The Center combines these services with vibrant cultural programs and events ranging from art gallery shows to cabaret performances to Queer Youth Prom.

With this combination of high-touch personal services and open cultural programs and events, the Center and similar organizations in dozens of cities across the country have become vital organizing hubs for LGBT issues. These centers build on their service relationships to educate members about issues affecting the LGBT community and connect members to issue advocacy and civic engagement campaigns.

Foster In-Person Member Communities | Maintaining strong relationships among members, leaders, and staff requires creating opportunities to connect regularly in person, whether that’s through hunting clubs, union halls, church support groups, local business networking events, or professional association conferences.

One of the most impressive member communities I studied is the Sixth & I Historic Synagogue in Washington, D.C. Over the past eight years, Sixth & I has turned the synagogue model on its head by transforming a defunct synagogue into a multicultural center with concerts, art exhibits, book signings, lectures, and comedy shows.

During the week that I visited Sixth & I, the synagogue hosted a concert with The Magnetic Fields, a book signing with Bob Woodward, a photography festival focused on India, and “Havdallah and Hoops” after the regular Shabbat services on Saturday. In addition to this cultural fare, Sixth & I engages members in political events, ranging from speeches by Al Gore and Nancy Pelosi to presentations on ethical eating to rallies in support of Israel. It may be unorthodox (literally and figuratively), but this eclectic, open-space approach led Newsweek to name Sixth & I one of the “25 Most Vibrant Congregations” in the country.

For some organizations, in-person community building is an Achilles’ heel. For example, although AARP has local chapters, only a small percentage of members are deeply engaged in face-to-face member communities. AARP members join for the discounts, insurance, and magazine, but rarely connect with other members just because they are a part of AARP. This lack of face-to-face contact limits AARP’s ability to develop trusted member communities and to activate its members for advocacy efforts. In the case of AARP, however, its sheer size allows it to turn out large numbers of people on important issues, as it did to support Obamacare.

Create Engaging Media Platforms | From the NRA’s popular hunting magazines to Focus on the Family’s podcasts and website to megachurches’ global televangelism broadcasts, media platforms can be a powerful tool for capturing the hearts and minds of members.

The most striking example of a media platform strategy comes from AARP, whose magazine’s circulation is three times larger than the next largest US publication’s. A lifestyle magazine with multiple versions targeted at various senior demographics, including a Spanish version, AARP The Magazine is a potent mechanism for AARP to influence its members on cultural and policy issues. The magazine is seen as a highly valuable member benefit: I was amazed by the number of AARP members who told me that AARP The Magazine, with its stories about senior health and wellness, over-50 celebrities, and world travel tips, was the primary reason they renewed their membership year after year.

Although media platforms are powerful advocacy tools, the most successful media platforms owned by civic organizations are primarily lifestyle-oriented rather than issue-oriented. With article titles like “Buck Fever,” “A Rifleman’s Paradise,” and “The Six Guys You Meet at Deer Camp,” the NRA’s American Hunter magazine is chock full of hunting stories, articles about the best hunting trips in the world, and tips for every aspect of hunting and marksmanship. Parents are drawn to Focus on the Family’s website and podcasts to find help on discipline issues, teen sexuality, and raising kids in a digital age. Lakewood Church’s broadcasts of Joel Osteen’s sermons are popular because of his modern and practical self-help messages about everything from family to fitness to finances.

Once these organizations have built popular lifestyle media platforms, they can deeply influence members on cultural and policy issues through stories and calls to action. Focus on the Family includes voter registration links and calls to “put your values in office” next to articles about Christian parenting challenges. And ten times a year, AARP moves beyond lifestyle issues to push more serious news, advocacy, and political information for seniors through the AARP Bulletin.

For the major membership organizations built in the 20th century, magazines, television, and radio have been the primary media platforms for connecting with members. For the next wave of membership organizations, the Internet, and particularly social media, will be critical for attracting members with news and information.

Unlike the one-directional media of television, radio, and print, social media has the unique potential not only to deliver content and information to members, but also to foster connections between members (online and in person). We have seen inklings of social media’s potential for community building in the rapid growth of Tea Party groups on MeetUp.com and the extraordinary growth of Occupy pages on Facebook during the heyday of the Occupy Wall Street protests. These social network platforms not only provide ways for these groups to disseminate information to members, but also give each group a tool for self-organizing, sharing, and connecting.

The Importance of Monetizing Membership

The most robust revenue engines for civic organizations are natural outgrowths of the benefits and services that drive their membership. Although the dues that members pay to gain access to the benefits and services generate significant revenue, most scaled-up civic organizations go beyond member dues by monetizing benefits and services so as to generate income every time services are used. It turns out that some kinds of benefits and services are easier to monetize than others, and no organization has perfected the art of monetization better than AARP.

AARP generates billions of dollars of revenue by endorsing insurance and travel products, providing discounts, and running ads in its popular senior living magazine. (See “The Big Business of AARP,” below.) Although the scale of AARP’s brand licensing program may seem unattainable for most civic organizations, versions of this basic business model are used by groups of all sizes: aggregate a group of consumers, negotiate better deals for these consumers, and then receive a referral fee from the companies providing the deals.

Historically, insurance benefits and financial services are the most common consumer aggregation services used by associations. Providing insurance and loans at lower cost and with better terms has long driven the development of membership associations for farmers, small businesses, professionals, and consumers.

Most large associations provide some form of insurance referrals and benefits. One of the fastest growing functional organizations launched in the 21st century, the Freelancers Union, has primarily focused on helping independent contractors obtain access to more-affordable health insurance options. With this core benefit, the Freelancers Union has grown to almost 200,000 members since launching in 2003.

Insurance and financial products are just the beginning of consumer aggregation strategies that membership organizations can employ. For example, for Union Plus (the package of discounts and services for AFL-CIO union members), the most popular benefits include 15 percent off AT&T cell phone plans and up to 25 percent off car rentals. In addition to providing valuable benefits for members, Union Plus has generated tens of millions of dollars in royalty revenue to help sustain the operations of the labor unions.

Even at the local level, community organizations are tapping into this revenue stream. Local organizations raise thousands of dollars a year through referrals of customers to banks and credit unions; local business associations garner fees from a range of vendors who present and market their services at association events and conferences; and local immigrant organizations receive referral fees for recommending members to trusted legal services.

THE BIG BUSINESS OF AARP

With 40 million members and an annual budget of more than $1 billion, AARP is the undisputed king of membership organizations. AARP has perfected the benefits and services model of functional organizing.

Like all scaled-up membership organizations, AARP’s revenue base is derived from its suite of member benefits and services. AARP also owns a huge for-profit company (with more than $6 billion per year in revenue) that manages royalties and deals with insurers, banks, and travel companies. This for-profit arm licenses AARP’s brand to insurers, financial services providers, and travel companies. In 2011, AARP’s for-profit arm generated more than $700 million in net income, which was used to cover more than half of AARP’s nonprofit operating budget.

The discounts, insurance, financial services, and travel deals that keep seniors renewing their AARP membership finance the lion’s share of AARP’s operating budget. AARP promotes these deals through its magazine (which also generates more than $100 million in ad revenue each year) and direct mail. The companies partnering with AARP each tout AARP’s endorsement in their own ads and promotions. This practice makes AARP’s brand ubiquitous in the senior market and further increases the revenue potential for the organization from endorsements and deals.

With a robust, independent revenue base, AARP is able to make large investments in advocacy and issue organizing. In 2009, AARP spent about $100 million on lobbying and made passage of the Affordable Care Act (aka Obamacare) its top priority. With these funds, AARP was one of the largest advocates for passing the bill: more than 1.5 million members took part in town hall meetings and conference calls; more than 1 million members signed petitions supporting the bill; AARP ran a barrage of television and print ads; and AARP created positive stories about health care in the nation’s largest circulation magazine (which it just happens to own).

Although AARP has faced criticism for being too business oriented and for being heavily tied to its insurance profits, the organization remains a trusted brand with seniors and one of the largest advocacy forces in the country.

Keys to Functional Organizing

Although every community is unique in its needs and opportunities, there is a core set of components that leads to successful functional organizing. Launching a functional organizing initiative, however, takes a serious and sustained commitment to shift an organization to a functional model. Many groups just aren’t ready to make this leap.

For organizations whose boards, executive leadership, and donors embrace a long-term strategy for becoming an indispensable part of their members’ daily lives, there are five critical components to launching a successful functional organizing initiative:

Understand Your Members’ Challenges | Companies spend billions of dollars every year trying to understand their customers. For leaders of civic organizations, the two most important questions to ask about your targeted members are: “What are their challenges in life?” and “What would make these challenges just a little bit easier?” Maybe you are working with parents trying to figure out pickup and after-school care; maybe you are working with families struggling to find reliable caregivers for their aging parents; maybe you are working with immigrants with only limited legal status straining to build credit. Whoever your constituents are, you must deeply understand their daily needs and figure out whether your organization can provide a helpful tool or resource.

Focus on What You’re Good at and Known For | Reputation is everything when it comes to scaling up membership. Build member benefits and services based on what your institution is already good at doing and what your community trusts you to do. If you’re known for housing issues, think about referrals for home insurance, mortgages, and contractors. If you’re known for ethical food issues, think about referrals to organic food restaurants, farm shares, and health food stores. If you’re known for health issues, think about prescription cards, vision discounts, and gym membership discounts. If you’re known for parenting and children’s issues, think about babysitting co-ops, discounts to local museums, and referrals to financial advisors for college saving.

Create Products and Services to Generate Profits | Profit is often considered a bad word in the social sector. But finding ways to monetize services and benefits in a self-sustainable way is crucial for scaling up membership. In some cases, direct service provision models—like classes, support groups, networking events, and health or legal services—can be made profitable. Consumer aggregation, however, is the more common path to developing profitable benefits. To succeed at consumer aggregation, focus on high-margin products and services (financial and insurance products instead of retailers and supermarkets, for instance) and fill a trusted referral gap for consumers by identifying high-quality providers (don’t provide the service yourself).

Join with Other Organizations to Negotiate Deals | Negotiating discounts requires organizations to have a large base of active members. Obtaining this kind of negotiating power often requires joining together with other organizations in your region or nationally. Build coalitions with other organizations in your sector to amplify your negotiating power and share the costs of setting up member benefit programs.

Find Funders Willing to Act Like Venture Philanthropists | Launching functional organizing ventures takes steady support from funders who are willing to shift into the role of venture philanthropists. Usually, funders make grants year after year to the same groups to achieve the same outcomes. But as venture philanthropists, funders make time-limited investments in high-risk functional organizing initiatives. The functional organizing projects that succeed should be fully self-sustainable within 5 to 8 years (and will achieve proof of revenue potential within just 2 to 3 years). Only a small fraction of functional organizing initiatives will succeed, so funders need to be willing to invest in a range of projects, carefully assess which are working, and let fail those that aren’t.

Creating a Virtuous Cycle

Immigrant organizations provide some of the most compelling examples of how functional organizing can build scale and impact at the local level. CASA de Maryland’s Multi-Cultural Center is located in the heart of the Langley Park neighborhood (an unincorporated area of Maryland), where almost two-thirds of residents are immigrants. The Multi-Cultural Center is the largest of CASA’s five immigrant “Welcome Centers” where CASA offers members a broad array of services.

In addition to providing direct services, CASA has also been in the forefront of policy fights for national immigration reform. In June 2012, President Obama announced that the US Department of Homeland Security would not deport “DREAMers,” young immigrants who came to the United States before they were 16, have graduated from high school, and have kept a clean record.

CASA sprang into action to help young immigrants throughout Maryland obtain the documentation and support they needed to qualify for this program. In a few short months, through individual outreach and legal clinics, CASA helped nearly 2,000 DREAMers apply for the program and become dues-paying CASA members.

CASA then immediately engaged these young immigrants in efforts to pass a state-based DREAM act in Maryland—a 2012 ballot initiative providing DREAMers with in-state tuition eligibility at Maryland’s public universities. During the election, CASA deployed the DREAMers and thousands more of its members as volunteers and canvassers to support the initiative. The initiative passed last November by a sixteen-point margin. “Our goal is to develop life-long members,” says George Escobar, who directs CASA’s social services. “This [the DREAMers engagement] is a great model of organizing and services working together.”

CASA de Maryland shows that organizations can tap into the symbiotic relationship between member services and social change organizing. The most successful functional organizing models create a virtuous cycle of support, engagement, revenue generation, and impact. Functional organizing models that focus on building deep relationships with members have the potential to reinvigorate civic institutions across the country and engage millions of Americans in reshaping the fabric of society.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Peter Murray.