No single organization or individual can pull off an effective storytelling campaign alone. (Photo courtesy of Exposure Labs)

No single organization or individual can pull off an effective storytelling campaign alone. (Photo courtesy of Exposure Labs)

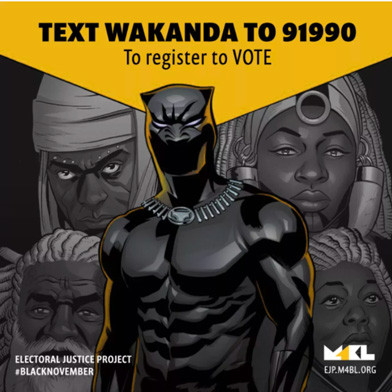

When Marvel’s Black Panther film released to record-setting audiences, the Electoral Justice Project saw an opportunity. Looking to advance its mission of “building black political power,” the organization launched #WakandaTheVote. The campaign built on the film’s powerful themes of community empowerment and cultural celebration, and provided organizers around the United States with tools to reach potential voters at screenings. The result: events everywhere from Dallas to Durham to register thousands of people to vote.

The power of #WakandaTheVote rested not only on using an incredibly entertaining story, but also on smart division of labor. Electoral Justice Project could have spent thousands of dollars producing videos about voting. Instead, it leveraged an existing multi-million-dollar film and invested in the organizing infrastructure around it—ultimately reaching its target audience at scale.

A social media graphic from the Electoral Justice Project’s #WakandatheVote campaign around the film Black Panther. (Photo courtesy of Electoral Justice Project)

A social media graphic from the Electoral Justice Project’s #WakandatheVote campaign around the film Black Panther. (Photo courtesy of Electoral Justice Project)

We know that storytelling is one of the most powerful tools we have for activating people. Effective stories transport us into the world of their characters; they leave room for us to insert our own experiences, and can overwrite bias and assumptions with details and counternarratives.

The social sector is investing in storytelling. But just telling stories is not enough. Many organizations struggle to produce compelling stories that actually move people. Meanwhile, many storytellers wrestle with how best to mobilize audiences who are hungry to act. What if we combined the superpowers of these worlds? As we increasingly embrace the power of storytelling, we don’t just need to tell better stories, we need better partnerships.

Are you enjoying this article? Read more like this, plus SSIR's full archive of content, when you subscribe.

Step One: Use Science to Inform Strategy

The science of storytelling doesn’t just tell us what makes one story better than the next. It also tells us that to use stories to drive belief and behavior change, we need to bring together the right ingredients, including:

1. Identify a Target Community and Tell Stories That Connect to Who They Are

People consume information that is entertaining, reflects their existing beliefs, or helps them be a better version of themselves. So, if we want to effectively engage people on issues, we must share entertaining stories that connect to what our target community cares about. For example, the soon-to-be-released documentary Game Changers is a fast-paced film following the stories of different elite vegan athletes. By focusing on a shared area of passion, athletic performance, rather than ethical arguments, the film reframes a conversation about veganism to reach a whole new audience.

2. Choose the Right Storytelling

When a story effectively transports us into the world of its characters, it can actually change our beliefs and willingness to act.

This starts with finding a great story that has the power to hold our target community’s attention. Research tells us that when a story effectively transports us into the world of its characters, it can actually change our beliefs and willingness to act.

Furthermore, when selecting the right story, we need to make sure the emotions it elicits connect to our impact goals. Different emotions lead people to do different things. Fear makes people “fight or flee.” Awe makes us self-reflect and open up to new perspectives. It is important that we be intentional about choosing the right emotion, based on the nature of the issue and the intended call to action. For example, we know that humor can close psychological distance on tough issues. A study by Caty Borum Chattoo at American University found that when mobilizing new support to address global poverty, a comedic documentary was more effective than a somber one, because it elicited positive emotions people wanted to feel.

3. Find the Right Messengers for the Story

Research tells us that the messenger is the message. It is not enough to simply create a great story, post it to your website, and wait for the change to begin. We need to go where people are. YouTube’s Creators for Change is putting this principle into practice, supporting popular video content creators to fight hate speech and extremism. These creators are trusted messengers ideally positioned to bring new communities into this movement, and are now integrating messages of tolerance into new videos on topics ranging from makeup to travel.

4. Pair Important Stories With a Clear Call to Action

Calls to action should be specific rather than abstract, allow people to feel like their action will make a real difference, and be something people actually know how to do. #WakandaTheVote was effective because the Electoral Justice Project went to where their target audience was and provided a concrete, meaningful, and actionable call to action: register to vote.

We can look to film-based advocacy campaigns as bright spots on how to do this work well.

Step Two: Cast the Right Characters

Given all these critical ingredients for building an effective storytelling strategy, it’s not surprising that it is difficult to get it right. It is nearly impossible for any single actor to do all these things well. Should we expect a filmmaker to transform overnight into a world-class coalition builder? Or an advocacy organization to produce awe-inspiring stories? Of course not. Rather than looking to build a storytelling strategy alone, start with the catalyst ingredient: building better partnerships from the beginning.

As we start to design campaigns that benefit from the power of stories, we can look to film-based advocacy campaigns as bright spots on how to do this work well. These campaigns show us that we need to include the right partners playing the right roles. This means thoughtfully casting the three leading characters: the storyteller, the strategic convener, and the funder.

The Storyteller

A great storytelling strategy needs a great storyteller. Not all content is created equal. Organizations frequently struggle to tell compelling stories that capture the attention of their target communities. Often when leaders ask teams to “embrace storytelling,” their teams develop new content too quickly, costing the advocacy world millions of dollars to produce stories people barely see.

At the same time, there is a whole industry of artists deeply dedicated to this craft. Documentary filmmakers, in particular, often follow a story and its characters for years at a time. In turn, they end up with a deeply visceral understanding of an issue, and can offer a refreshing perspective to building outreach and capturing the public imagination.

The storyteller role can do many different things. This person or group can identify the right stories, which can include sharing existing films, co-creating new cuts, and even producing new stories altogether. The storyteller can also be an authentic voice to speak to audiences, serve as a magnet to draw people out, and share first-hand testimony about an issue.

For example, Girl Rising is a feature film and global campaign for girls’ education. Playing the storyteller role, the documentary team worked closely with advocacy partners to produce a multi-million-dollar film that could bring different campaigns to life. The team cut shorter versions to highlight particular sub-themes and produced new short-form content featuring local voices to connect hundreds of organizations to beautiful, high-quality storytelling that would typically be out of reach.

Film screenings to offer a new way to organize for impact. They can catalyze social movements and mobilize unlikely audiences to action. They can get the attention of leaders. They can build creative new coalitions, and in so doing, set-up the necessary conditions for political change.

The Strategic Convener

Great storytelling needs strategic thinking to know which audiences and which calls to action they can inspire. For example, let’s look at film-advocacy campaigns: With traditional film screening, a group invites their existing supporters to watch a movie. After the film plays, there is a panel discussion. Sometimes there is a call to action, usually to give money or sign something.

Instead, strategic conveners can host film screenings to offer a new way to organize for impact. They can catalyze social movements and mobilize unlikely audiences to action. They can get the attention of leaders. They can build creative new coalitions, and in so doing, set-up the necessary conditions for political change. In short, they can advance all kinds of different organizing goals by embracing something we all love to do: go to the movies. But to do this well, someone needs to play the essential role of the strategic convener.

The strategic convener must deliberately design a strategy to utilize story to its fullest potential. As Crisis Action Network’s creative coalitions handbook puts it, this is a role where “you are part talent scout, part orchestra conductor, part sports team coach.”

Doing this well requires that the strategic convener identify a very specific change goal, develop meaningful calls to action, and find partners who can agree on this vision for change. The strategic convener must understand the power dynamics in a given issue area and artfully pull together a target community—whether local advocacy groups, lobbyists, community leaders, or media—in the right way.

The team at Participant Media, a social impact media company, often plays this role. It recently ran an impact campaign for its documentary RBG, which tells the origin story of US Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. In collaboration with Magnolia Pictures and CNN Films, part of the campaign focused on mobilizing the legal community. Following screenings with law schools and law firms, discussions were held to identify actions the firms could take toward women’s equality, both within the organization and through pro bono work.

The person or group playing the strategic convener can vary, but whether it is a consulting “impact producer, ” an organizer within an advocacy group, or the social impact team at a film company, it is essential to intentionally fill this role from the beginning, at the hub of the effort.

The Funder

This brings us to the last character in our cast: the funder. Building stronger bridges between the art and advocacy worlds requires systems-level investment. Forward-looking funders can help create the time and capacity to develop not only one-off partnerships, but also a robust ecosystem of collaboration. Through smart investments, we can build and hone new creative models of partnership that realize the fullest possibilities of a storytelling strategy.

Underwater imagery of coral bleaching in New Caledonia taken during the filming of Chasing Coral. (Photo courtesy of Exposure Labs)

Underwater imagery of coral bleaching in New Caledonia taken during the filming of Chasing Coral. (Photo courtesy of Exposure Labs)

Lots of different groups can play this role. Philanthropists and foundations can fund campaigns and create expectations around better partnerships. Executive producers and supporters of great films can make sure to allocate funding to the film’s impact campaign. And advocacy organizations can designate funding for story-driven campaigns and events. Doc Society, a nonprofit dedicated to maximizing the impact of documentaries, does a great job of creating systems-level investment in creative coalitions. Through Good Pitch, the organization’s global series of one-day “pitch forums,” it connect storytellers with upcoming films to a network of potential strategic conveners and funders. In so doing, it provides the space for these characters to come together and build better partnerships.

Posters written by constituents addressed to their local lawmakers as part of the Dear South Carolina campaign around Chasing Coral. (Photo Credit: Exposure Labs and the Conservation Voters of South Carolina)

Posters written by constituents addressed to their local lawmakers as part of the Dear South Carolina campaign around Chasing Coral. (Photo Credit: Exposure Labs and the Conservation Voters of South Carolina)

Case Study: Chasing Coral’s #DearLegislator Tour

Casting the right characters was important to setting up the impact campaign for the Emmy-award winning film Chasing Coral (led by a co-author of this article). Using beautiful underwater imagery and a character-driven adventure narrative, the film brings audiences to a world hidden under the waves to make the impacts of climate change feel real and personal. In designing the film’s outreach strategy, the impact team focused on launching pilot campaigns in the US Southeast. As a production company, Exposure Labs plays the role of the storyteller and collaborates closely with the Conservation Voters of South Carolina (CVSC) as the strategic convener. The film’s executive producers—philanthropists looking to mobilize political action—play the role of funder.

The team started by outlining a shared change goal: pressuring state lawmakers to support clean energy policy. Moving toward this goal, CVSC is using the film to mobilize a network of local community partners and trusted messengers across a few target districts under the banner of the “Dear South Carolina” campaign. To support this work, the Chasing Coral team produced new local content and send cast members to events. Post-screening discussions connect the dots to specific local solutions: South Carolina’s own renewable energy possibilities. The call to action is for the audience to show their visible support for clean energy through public posters addressed to their local representative.

With dozens of events hosted by local messengers—including Republican politicians, church leaders, and military veterans—diverse constituents are coming out to watch Chasing Coral across the region. While the campaign is ongoing, it has already captured the attention of state lawmakers. Because they are hearing from atypical constituents not usually tied to environmental movements, these local legislators have attended screenings, and some have shifted their support for solar bills. Excited by the possibilities of a collaborative film-based outreach strategy, CVSC is now expanding outreach to veteran communities using a new film about military leadership in the clean energy transition: The Burden.

To benefit from the power of stories, organizations should look for opportunities to build bridges with unexpected allies in the creative community. We need people driven by the issue at hand to make strategic decisions about campaign goals, target audience, and calls to action. We need great storytellers who know how to craft a compelling and effective story. And, of course, we need better funding for this sort of storytelling innovation, which means an investment in better partnerships.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Samantha Wright & Annie Neimand.