Meals on Wheels Community Outreach Director Annette Read hands-off paperwork to a volunteer in Durham, North Carolina. With much of the program’s client base falling into at-risk categories, administrators, drivers, and clients have had to minimize personal interactions. (Photo courtesy of Bisi Cameron Yee and Activate Good’s “Look for the Helpers” Photojournalism Project; full collection at ActivateGood.org/Helpers)

Meals on Wheels Community Outreach Director Annette Read hands-off paperwork to a volunteer in Durham, North Carolina. With much of the program’s client base falling into at-risk categories, administrators, drivers, and clients have had to minimize personal interactions. (Photo courtesy of Bisi Cameron Yee and Activate Good’s “Look for the Helpers” Photojournalism Project; full collection at ActivateGood.org/Helpers)

At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, a shelter in the Midwest serving 16 different families had to quickly overhaul its operations. This included changing meal-time routines to account for social distancing, helping parents transition their children from in-school to online learning, and reducing the number of on-site staff to limit the potential spread of the virus. It also had to temporarily stop its volunteer program and in-kind donations, and cancel its major annual fundraising event.

The pandemic forced these kinds of dramatic changes on organizations on all sectors, but it particularly challenged nonprofits: While demand for services typically increases during economic downturns, nonprofits are reliant on lean operating structures, volunteer help, and face-to-face service provision. Yet our research on the personal and professional changes US nonprofit workers experienced shows that organizations quickly adjusted to COVID-19 safety protocols and adopted new policies in response to new needs. Despite the difficulties, and counter to the common perception that nonprofits lack efficiency and competence, many have proved nimble and innovative, and have managed to successfully weather the storm so far.

But what’s on the horizon for these organizations as new virus variants and simultaneous expectations of “returning to normal” emerge?

By becoming “learning organizations”—organizations that engage in an intentional, ongoing process of reflection, assessment, and adaptation—nonprofits now have a chance to go beyond simply incorporating pandemic protocols into risk-management plans and returning to pre-pandemic mode, and instead consider what they have learned from the changes they’ve made and whether to keep or abandon them.

Changes to Human Resources: Keep or Abandon?

The pandemic has required that nonprofits across the United States re-examine and take up new and often untested staffing practices and policies. These, in turn, have changed the way people think about and conduct their work.

Working from home is a big example. One nonprofit worker we talked to described working from home pre-pandemic as “kind of taboo,” but our analysis of research across 43 states found that nonprofits shifted to allow virtual work whenever possible. For some nonprofits, it was a matter of prudence, even a reflection of organizational values to prioritize worker safety; for others, it was about adhering to local mandates.

Nonprofit workers were also asked to do more and/or different tasks while also shouldering a personal—and often inequitable—COVID-19 impact. Women were unevenly burdened by child-care responsibilities—indeed, two-thirds of the nonprofit workers we surveyed found themselves juggling child-care responsibilities amid changing work responsibilities. Meanwhile, people of color found themselves disproportionally impacted by the COVID-19 virus itself while a nationwide racial reckoning highlighted long-standing systemic barriers to equitable workplaces.

Finally, some nonprofit workers began to shift how they thought about their motivations for work. One female nonprofit worker employed by a capacity-building nonprofit described herself as 100-percent committed to the sector pre-pandemic. Now she expresses a burgeoning interest in B Corporations, describing them as appealing professionally to her and “less complicated than the nonprofit model.” As nonprofit workers anticipate another phase of pandemic-related changes, they may start looking out for new opportunities that could lure them into switching organizations, even sectors.

These examples reflect major shifts in the nonprofit workplace. Yet today, many organizations are insisting on a “return to normal”—a 2019 vision of life and work that in some cases disregards the extended fatigue, stress, and trauma organizations and individuals have experienced over the past year and a half.

We urge an empathetic, collaborative, and compassionate leadership approach during this next transition phase. Though organizations made hasty changes to human resources at the onset of the pandemic, many of those changes have now been battle-tested for more than 15 months. Pre-pandemic arguments against flexible time and virtual work often no longer stand; workers have continued to perform. Leaders should assess these policies for their durability, respecting how they served the organization during the pandemic and thinking through how they could continue to serve it. For instance, the time may be ripe for nonprofits to standardize remote work practices or create a hybrid work policy that fits organizational needs while also supporting worker strengths and preferences. On the other hand, what worked at the beginning of the pandemic may need changing or refining.

During this process, two-way communication with workers is essential. The nonprofit workers we interviewed indicated that their trust in leadership was tenuous, but one way to shore up trust is to invite worker input into decision-making processes—including decisions about back-to-office plans and safety issues.

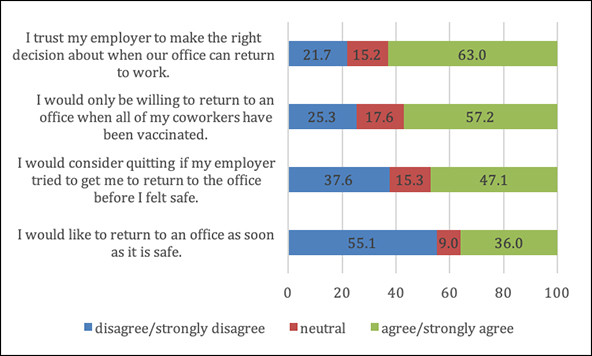

Surveys like this one from Nonprofit HR give workers a voice and allow organizations to quickly assess how workers feel about returning to the office. Sometimes organizations can achieve adequate transparency using a one-size-fits-all (or -most) means; other times, individual conversations can be more productive and help increase performance and retention, especially if staff members have different needs.

Whatever the method, leaders need to respond respectfully to worker feedback and recognize the role communications and transparency play in building trust and creating buy-in to change. One nonprofit worker we surveyed described her experience of nonparticipation this way: “The president of the organization and upper leadership made the decision to return full time to the office, without staff input. At no point was staff surveyed or asked about how we felt. …There was a claim that the president would be doing office walk-throughs ‘to make sure there were butts in chairs.’ I found this so condescending and disrespectful, as [everyone at the] organization has already proven they [can] do their job and do it well over the past year that they have been fully remote.”

In contrast, the vice president of the family shelter we mentioned at the beginning explained that the pandemic increased trust within the organization, in part due to organized weekly team discussions about empathy and understanding. She noted, “We really tried to take care of the people [staying at the shelter] but also make sure that we were taking care of our staff and ourselves …. we trusted that everyone was doing the best that they could.” This approach likely contributed to the organization not losing any staff over COVID-19 concerns.

COVID-19 Program Innovations: Keep, Abandon, or Change?

The protracted and unprecedented nature of the pandemic has also complicated nonprofit programming and demanded that organizations make major changes to remain mission-viable.

Changes include operational shifts, such as transitioning in-person programs to virtual platforms and developing new digital communication strategies. In some cases, the primary challenge was adapting programming to accommodate COVID safety protocols. For example, state-level reporting indicated that nonprofits took on the extra expense of personal protective equipment and in some cases shifted from volunteer-run to staff-led programs. Organizations also had to temporarily or permanently drop programs that didn’t work under these new restrictions.

Other nonprofits needed to tweak service eligibility criteria to account for emerging needs. For example, National Voluntary Organizations Active in Disaster, which traditionally focused on natural disasters, extended its scope to include pandemic response. Organizations like health and human-service nonprofits changed modes to become first responders, while others, such as arts organizations, adapted programming and development to sustain their livelihood through the pandemic.

However, while COVID-related innovations continue to stretch nonprofit capacity, this stretching isn’t all bad—adopting new technologies, widening service criteria, and discarding less-viable programmatic activities are productive evolutions. As one nonprofit worker we surveyed said, “I feel the COVID-related changes—while stressful, painful, difficult, and challenging—will actually poise our organization to be more sustainable and to better serve our community.”

Nonprofit leaders can formulate a collaborative, integrated process to assess which innovations have served the nonprofit's mission well, which innovations have not, and whether to re-incorporate any pre-pandemic programming beneficiaries have missed. One way to start this process is by using a clear-cut SWOT analysis to identify the innovation’s “strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, or threats,” or using an assessment like Leavitt’s Diamond that emphasizes alignment between people, structure, tasks, and technologies. These exercises can identify any quickly patched together adaptations that nonprofits need to make more durable. They can also help update measurement and evaluation benchmarks, and highlight new efficiencies that should stay in place.

As with human resources, this process works best when it’s collaborative—when it’s informed by a cross-functional working group; a staff survey; a venue for employee-driven, self-organized exchanges; or even listening sessions with various staff groups. Equity and inclusion should be a central consideration, and considerations on how to move forward should balance the long-term stability of the organization with short-term efficiencies. As with any organizational change, transparency is important. A membership association we know began talking about its return-to-office plans last spring using staff surveys and all-organization meetings to communicate plans and rationales to engender trust. Communicating what the process entails; rationales for any reversions, adoptions, or modifications; and the impact of the change on employees will make employees more likely to support the change. When it comes to decisions about programming, organizations should also be sure to engage funders and other partners.

Finally, after gathering input and determining which innovations to keep, abandon, or change, organizations should update policies, procedures, and even staff performance evaluations to reflect the new modus operandi.

Nonprofits are known for habitually underinvesting in their capacity, including practices and tools that could equip them for this moment of organizational learning. But it is time to rise to the occasion—to lean in, once again—by engaging staff and partners, analyzing organizational and programmatic changes, and probing what will continue to serve the mission well in this next phase.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Amanda Stewart, Marlene Walk & Kerry Kuenzi.