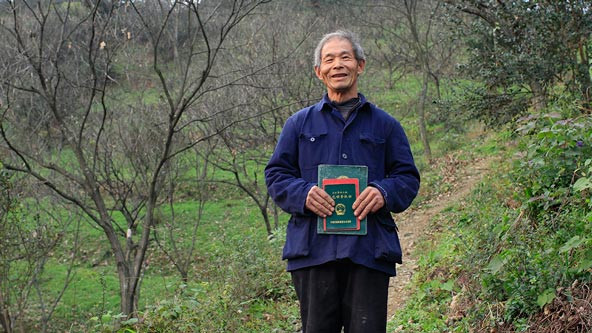

A Chinese farmer holds documents that establish his rights to his land. (Photo courtesy of Landesa)

A Chinese farmer holds documents that establish his rights to his land. (Photo courtesy of Landesa)

In just four decades, about 800 million people in China have climbed out of poverty, lifting their income above the benchmark $1.90 or less per day. Remarkably, the country’s poverty rate is now less than 1 percent, down from more than 80 percent when I first conducted fieldwork in China’s rural Sichuan province in the 1980s.

What may be surprising about China’s economic miracle is that those of us working in global philanthropy and social change organizations arguably had little to do with it. What may be even more shocking is that we've failed to pay enough attention to China's achievement and the lessons it holds.

The most successful eradication of poverty in human history deserves a thorough examination. I've identified five key lessons from the nation that should inform our own strategies:

1. Expand Primary Healthcare and Literacy

Mao Zedong, the founder of the People's Republic of China and its leader from 1949 to 1976, put forth many policies that were more than problematic. But his focus on extending primary health care and literacy to the masses while the country was still very poor paid social dividends and set the stage for China’s economic rise.

Are you enjoying this article? Read more like this, plus SSIR's full archive of content, when you subscribe.

In 1949, the average life expectancy in China was 32 years, and the literacy rate was below 20 percent. By 1980, although China was still very poor, immunizations and primary health care had spread throughout the country, lifting the average life expectancy to 67 years. And literacy, by 1982, had reached 66 percent, including 89 percent of young people between the ages of 15 and 24.

Under Mao, the government implemented the “barefoot doctor” program. It trained about 1 million rural community members to provide immunizations, preventive care, and health education to the nation's people, more than 80 percent of whom then lived in the countryside. Fortunately, this aspect of China’s success story has inspired numerous similar community health worker interventions in other countries, including Bangladesh and Liberia. (Disclosure: The Liberia national program is funded by Co-Impact, a donor collaborative of which my chairman, Richard Chandler, is a core partner.)

By 1978, China's still poor but relatively healthy and educated people pushed the nation's human development index close to levels seen in much more prosperous countries.

2. Prioritize Agriculture and Land Rights First, Then Industry

In most low-income countries, the vast majority of workers are farmers, as was the case in China until recently. Giving those farmers an opportunity to climb the social mobility ladder is a crucial first step toward economic prosperity.

China accomplished this in the late 1970s through the implementation of the household responsibility system, which broke up communal and family farms. This broad distribution of assets in the form of land gave the nation's rural workers—who then made up 80 percent of the population—the opportunity and incentive to produce, prosper, and grow their way out of poverty, as the economist and author Joe Studwell writes in his book How Asia Works.

Land reform sparked inclusive economic growth in China, just as it did in Taiwan and Japan after World War II, Studwell notes. Making the nation's small farms more productive not only fed families, it freed them. Released from the burden of communal farming, they spent fewer hours in the field while producing more crops. With their newfound free time, they took advantage of emerging and more remunerative non-farm work opportunities in both rural and growing urban areas. And with their extra spending power, they served as a rapidly growing market for new, rising industries.

It is hard to name a Sub-Saharan African country that couldn’t benefit from following China's path of jumpstarting broad and inclusive economic growth by providing clear, long-term land rights and investing in farmers. From Mali to Mozambique, farmers in much of Sub-Saharan Africa do their work without secure rights to the land they rely on, with little support from government. This is particularly true for the roughly half of Africa's farmers who are women, who face great hurdles obtaining secure land rights and accessing markets.

In countries where most of the poorest people are working in agriculture, philanthropic and social change organizations need to double down on empowering smallholder farmers. Their success is critical to upward mobility, the expansion of the middle class, and economic growth.

3. Advance Policy Reforms That Harness the Power of Markets

In 1978, China’s GDP per capita was about $156— the same as Zambia’s and Bangladesh's and significantly lower than the Asian and African averages. In 2017, it was $8,827. China's immense progress arose from economic policy reforms that unlocked the entrepreneurial spirit of farmers, merchants, and future magnates, freeing up markets and unleashing innovation.

The changes came in waves, beginning in the late 1970s with the land and rural reforms that provided economic freedom for farmers to produce and earn more. These spurred the dramatic reform and rise of the largely private and entrepreneurial township and village enterprise sector during the 1980s and early 1990s. Finally, China's rapidly industrializing economy of today benefited from improvements in the nation's corporate governance system, which fed a boom in domestic stock markets and helped move many leading private and state-owned actors onto the stage of major international exchanges.

Too little global philanthropy goes toward pushing for changes to government policy that unlock entrepreneurial energy, which, as China demonstrates, plays a huge role in a nation's economic development. Continuing to underinvest in the development and implementation of smart policy reforms that unleash entrepreneurialism will mean countries that remain stuck at 1970s levels of economic performance may never move closer to prosperity for all.

4. Improve Governance Through Decentralization and Market Reforms

China is not typically perceived as the gold standard for good governance. But substantial and gradual improvements following the Mao era helped make the country’s economic miracle possible.

Immediately after the Cultural Revolution and following decades of strong central control, China’s leaders didn’t just allow decentralized local experimentation with new economic approaches, they encouraged and sometimes sponsored it. Indeed, it was local officials who first tried decollectivizing farms. When that succeeded, the policy was taken up nationally, demonstrating the potency of local knowledge and bottom-up initiatives. This innovative approach was central to the transformation of China's economy, as Sebastian Heilmann points out, and demonstrates the power of solutions that go outside the rigid international “best practices” often imposed by foreign economic advisors.

China also provides us with an unexpected answer to the vexing and often asked question in international development circles: Does good governance lead to poverty reduction or vice versa? Please note China’s unexpected answer: Good governance and poverty reduction are mutually reinforcing, as Yuen Ang’s book How China Escaped the Poverty Trap suggests. She makes a compelling case that it is possible to make economic progress without first concentrating on improving weak institutions. Rather, unleashing economic forces can create a pull on institutions, incrementally improving them. And those boosts in governance can then unleash more economic energy. Additional evidence for this unexpected cycle within and beyond China's borders can be found in the excellent book The Prosperity Paradox.

5. Help Women Drive Economic Growth

Whether or not women “hold up half the sky” in China, as Mao once said, they have benefited from relatively more agency than in many other emerging economies. Since the 1960s, China’s women have had a higher labor force participation rate than nearly any other country, according to the World Bank. They contribute 41 percent of China’s GDP, a higher rate than even women in North America, according to a report by Deloitte China. Chinese women attend university at a higher rate than men and they make up 57 percent of the world’s self-made female billionaires. China could not have achieved its economic success without empowering and tapping the talents of its women.

Using the Insight

The fastest growing economy in Africa, Ethiopia, has applied many of these lessons to great effect. Its widespread community health worker program has expanded primary health care and achieved among the most notable declines in child and maternal mortality in all of Africa. The nation has also doubled down on investment in agriculture, founding the Agricultural Transformation Agency in 2010 to lead the work. It is clarifying formal land rights and establishing, a national agricultural extension service to increase farmers’ yields and income. And the country is also building industrial zones to increase manufacturing exports.

The results are impressive: Ethiopia's GDP growth has been 7 percent or more each year since 2004 and regularly hit double digits, most recently 2017, according to the International Monetary Fund.

However, more can be done. Social change organizations focused on poverty and the donors who support them, such as the Chandler Foundation, where I work, should ask how we might help Ethiopia's government and others like it do even more using the power of insights from China's experience.

Changing Philanthropy

I am not saying that China has demonstrated best practices that should be applied everywhere. But it has achieved the greatest success in pulling people out of poverty in human history and may have found pathways out of poverty that we can adapt and adopt.

The nation's unorthodox economic success highlights the important roles played in the process by policy, governance, and a thriving business sector—topics that don’t receive enough attention from global philanthropy and social change organizations. I have noted a few lessons from China’s experience, but surely there are many more. By humbly approaching further investigation with an open mind, we can uncover additional insights that will challenge our approaches to fighting poverty and help us spread prosperity to more people around the world.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Tim Hanstad.