ShoreBank’s Kenwood Branch on Chicago’s South Side, three months before the bank was closed by the FDIC. (Photo by Carlos Javier Ortiz)

ShoreBank’s Kenwood Branch on Chicago’s South Side, three months before the bank was closed by the FDIC. (Photo by Carlos Javier Ortiz)

On Aug. 20, 2010, the Illinois Department of Financial & Professional Regulation closed ShoreBank, the nation’s first and leading community bank, and appointed the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) as receiver. The closure was not unexpected. Reports of the bank’s problems—and a potential rescue—had been circulating for months. But the closure brought to a bitter end an iconic example of progressive social enterprise.

During its 37 years, ShoreBank Corporation became the United States’ leading social enterprise of its kind: its for-profit bank subsidiary was the largest certified Community Development Financial Institution (CDFI) in the nation. Its social impact was significant: more than $4.1 billion in mission investments and more than 59,000 units of affordable housing financed. In 2008, ShoreBank had more than $2.4 billion in assets and earned more than $4.2 million in net income. It had inspired a national movement of community development financial institutions, shaped federal community investment legislation, and served as a role model for dozens of progressive banks. The company also had influence abroad, overseeing social and economic development projects in more than 60 countries and working with Muhammad Yunus to capitalize Grameen Bank and administer microloans to the poor.

So why did ShoreBank fail? What lessons can the social enterprise community learn from its record of success? And what can be learned from its closure?

The full answers to these questions will take years to answer, as the legal and regulatory process of winding up the bank’s affairs continues and the FDIC will not complete its study of the bank until August 2013. This has limited the freedom of participants to speak fully about their experience. But we have had the privilege to speak with two of ShoreBank’s founders and others who are familiar with the bank’s history and activities.1

To extract lessons from ShoreBank’s failure one must understand its remarkable history. ShoreBank innovated at every turn—economically, socially, and organizationally. For almost four decades, it stood for the proposition that neither race nor wealth nor geographic location should bar an individual from access to capital to buy a home, build a business, or develop a community. The bank’s motto, “Let’s Change the World,” served as a marketing device and a rallying cry for progressive community activism. In time, however, it also became a political red flag, stirring to action opponents of the causes ShoreBank advocated.

Various explanations have been offered about why ShoreBank failed. One view holds that the bank was capsized by the financial tsunami brought on by the subprime mortgage crisis. Another view holds that it was management errors and misjudgments by regulators that made the bank vulnerable. And still another view holds that it was the highly partisan politics of Washington, D.C., that prevented the needed capital infusion. Although there is some evidence for each theory, none is complete in itself.

Part of the challenge of extracting lessons from ShoreBank’s failure is to disentangle various economic, governance, and political factors and understand how each contributed to the bank’s demise. In his famous study of the Cuban Missile Crisis, The Essence of Decision, Graham Allison examined the actors, events, and conditions of the 1962 confrontation through three conceptual lenses: rational decision making, bureaucratic decision making, and political decision making. No single lens provided an adequate perspective to understand all that took place, but the three perspectives complemented one another and shed light on the considerations facing President John F. Kennedy and his administration. We employ a comparable approach, looking at ShoreBank’s operating environment, culture, and decision making to illuminate what is known—and not known—about the organization.

A DIFFERENT BANK

ShoreBank was founded in 1973 in Chicago by a small group of colleagues from the Hyde Park Bank. In the late 1960s, Ronald Grzywinski, Hyde Park Bank’s president, and his colleagues Milton Davis, Jim Fletcher, and Mary Houghton had launched a successful urban development division focused on a minority-owned small business loan program. They were community activists as well as bankers, with a passion for changing the economic future of inner-city neighborhoods. These were the days of redlining, a banking practice that systematically denied credit to people in urban, low-income, minority neighborhoods. Nonprofit economic development organizations, although strongly mission driven, were limited by their ability to attract philanthropic support. As professional bankers, the colleagues envisioned a different approach to address the twin problems of access to capital and urban decay.

The vision was simple and radical: The bank would become an “agent of change,” promoting economic redevelopment by supporting viable inner-city businesses that would provide goods, services, jobs, and housing. A commercial bank could leverage capital from deposits and make loans to amplify the impact of its shareholder equity.

A 1970 amendment to the Bank Holding Company Act placed all bank holding companies under the supervision of the Federal Reserve Board. Two years later, the board issued a list of permissible activities, which included allowing bank holding companies to invest in community development corporations if the primary purpose was community development for low- and middle-income people. “That led us to expand our idea—from using a bank to using a bank holding company,” remembered Mary Houghton, a ShoreBank co-founder. Luckily, the Federal Reserve Board then issued a favorable interpretation of its own regulation that reinforced the belief that the bank could be a community development organization.

In August 1973, the founders acquired a small bank, the South Shore National Bank, with $800,000 of equity capital from a small group of private investors and a $2.25 million loan from American National Bank. After the Federal Reserve Board approved the creation of ShoreBank Corporation in December of the same year, the new bank began operating under the auspices of the holding company. This structure enabled the founders to join regulated banking activities with economic development activities. Grzywinski and his co-founders believed that access to credit was only one of the keys to successful community development. Affiliated for-profit and nonprofit organizations were needed to support local entrepreneurs with higher risk lending and to provide technical assistance services. As a bank holding company, ShoreBank could offer a more potent mix of financial products and tools to boost economic development. In 1973, this dual mission approach was a radical idea.

The intention, explained Grzywinski in a 2008 interview, was to “use all of the bank’s resources to bring about redevelopment” in an “almost totally minority neighborhood with all of the symptoms of deterioration.” Said Houghton: “Our goal was to actually reverse the deterioration in the housing market [in Chicago] and be a catalyst for appreciation in a specific local market. If we hadn’t concentrated our efforts but had … dispersed our lending in a larger catchment area, we wouldn’t have really changed the nature of a market.”

ShoreBank differed from traditional banks in both what it did and how it did it. These differences created social value for the community, but they presented challenges because they often came at a financial cost. According to the bank’s founders, it took a decade to achieve breakeven for banking operations. On the deposit side, lower deposit minimums—designed to make the bank available to all regardless of socioeconomic level—meant smaller account balances than the industry average. Time and creativity were needed to create a sustainable model for serving these accounts profitably. Moreover, ShoreBank’s loan business had smaller average transaction sizes than traditional banks, which meant that fees collected as a percentage of administering the loan were less than larger loans typical in upper income markets, although they required the same administrative time. And, as Houghton explained, loan officers were asked to make assessments of community improvement a priority: If it was good for the community long-term, then they were asked “to go to extra lengths to find a way to structure the deal so that it was bankable.”

Mission mattered. The ethos of moderate financial returns and strong social returns was made possible, in part, by the expectations of ShoreBank’s investors. ShoreBank stock was privately held by a small group of shareholders (which ultimately grew to 75), including religious organizations, nonprofits, and community organizations, as well as insurance companies, banks, and trusted corporations and individuals. As Grzywinski explained, this composition meant that all the investors in ShoreBank “invested with the understanding that the primary purpose of their investment is to do development and not maximize return on capital.”

At the same time, ShoreBank needed ongoing access to growth capital, in part because of the bank’s modest profitability and the limited pool of socially inclined capital available in the United States. The closely held nature of ShoreBank by a small number of mission-aligned investors created some long-term structural issues. Grzywinski explained that none of the shareholders, including the founders, had any liquidity for their shares. “That’s a real problem,” he said, “and it’s a real limitation on growth.”

THE GROWTH YEARS

For the first decade ShoreBank focused almost entirely on the South Shore area of Chicago because the bank founders wanted to work with local decision makers who had a deep understanding of the markets in which they were working. In the early 1980s ShoreBank began lending to a growing number of people and businesses in adjacent neighborhoods, and in 1986 it opened a new branch in another Chicago neighborhood with similar needs.

This expansion was tied to the founders’ goal of creating a replicable model. That belief was realized in 1987 when an invitation came from the Winthrop Rockefeller Foundation for ShoreBank to help start a banking operation in rural Arkansas, called Southern Development Bancorporation. ShoreBank helped raise the capital and managed the bank for a number of years until Southern Development Bancorporation’s board took over. Not long after the Arkansas project, ShoreBank initiated a program in Michigan, and then in Cleveland and later in Detroit.

In 1997, ShoreBank became the first banking corporation in the United States to address environmental issues. Through a partnership with Ecotrust, an environmental organization in Portland, Ore., ShoreBank Pacific was created as a federally regulated bank focused on the underbanked area of environmental business development. The mission was timely and the founders viewed it as an opportunity to expand ShoreBank’s deposits and operations.

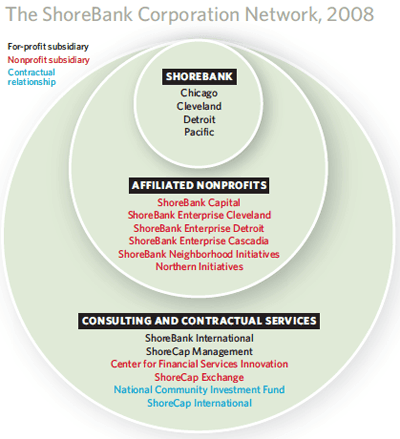

In each market where ShoreBank created a federally regulated bank, it also created an associated nonprofit—such as ShoreBank Enterprise Cleveland, ShoreBank Enterprise Detroit, and ShoreBank Enterprise Pacific (later renamed ShoreBank Enterprise Cascadia)—which predominantly focused on higher risk business lending. The founders saw these additional activities as critical to their theory of change. Incorporated as nonprofits, the organizations were largely self-financing through their operations, supplemented by grants, and were not financed by the ShoreBank holding company.

ShoreBank also started other nonprofits and for-profits to further its social mission. For example, the Center for Financial Services Innovation grew out of an opportunity to deliver asset-building services to the underbanked. ShoreBank executives often were asked to speak in the United States and abroad about their mission-driven approach to banking and to partner with other social entrepreneurs. In 1988, ShoreBank organized a for-profit consulting company to manage all of this activity professionally.

By 2008, the ShoreBank Corporation was a complex organization consisting of three circles of activity. (See “The ShoreBank Corporation Network, 2008” chart below.) The center circle—ShoreBank, the for-profit, federally regulated banking business—accounted for the bulk of its $2.4 billion of assets, making a variety of community-focused loans. The second circle included the nonprofit organizations that provided complementary services to banking and nonbanking clients. A third circle was composed of the contractual and consulting services, which enabled ShoreBank Corporation to assist other mission-driven organizations. It is important to note that the FDIC’s closing of ShoreBank affected the Midwest bank, but not the other components of the holding company, which now operate as independent organizations.

ShoreBank’s growth brought problems, however. In Community Capitalism, Richard P. Taub described internal challenges created by ShoreBank’s rapid expansion. He noted the heavy travel schedule of ShoreBank’s founders, and a management structure that required much direct supervision. He also noted that ShoreBank had difficulty hiring future leaders who had top banking skills and a commitment to social values. ShoreBank’s Cleveland and Detroit banks were never as robust as the original Chicago bank, and Taub pointed to the challenges of operating in neighborhoods that suffered even greater levels of deterioration than Chicago’s South Shore.2 In our interviews, the ShoreBank founders discussed how they realized that markets such as Cleveland and Detroit required more management oversight than the bank was sometimes able to deploy as well as banking tools that were matched to cities with failing manufacturing industries and less homogeneous economic conditions.

These challenges were seen as part of the learning process; they never forced a rethinking of ShoreBank’s mission or its business model. Over time, the ShoreBank Corporation was “modestly profitable,” to use Grzywinski’s words. From 1998 to 2008, the bank achieved about an 8 percent return on equity with net loan losses only slightly higher than those of commercial banks. By the end of 2009 ShoreBank Corporation was the nation’s leading entity of its kind. The for-profit bank was the largest certified CDFI in the United States. And the holding company’s subsidiaries and affiliates had made $4.1 billion in mission-driven loans. Through its international activities, ShoreBank provided consulting services in more than 60 countries and trained almost 4,000 bankers who provided approximately $1 billion a year in international community development loans.

This catalytic role was one of the most satisfying outcomes for the bank’s surviving founders, Grzywinski and Houghton. “We have made it legitimate for ourselves and others to use the nation’s banking system to advance the cause of development,” said Grzywinski. More broadly, we have contributed … to democratizing the availability of private nongovernment credit to lowincome and otherwise disadvantaged people. And we have done that in many parts of the world.”

Unfortunately, the world was about to change.

FINANCIAL MELTDOWN HITS CHICAGO

ShoreBank’s social enterprise accomplishments ran headlong into the 2008 financial crisis. The impact was most severe on the bank’s risk management and capital requirements. Management felt strongly that lending money, particularly to lower income people disproportionately affected by the economic crash, was imperative. It focused on customers who had been the victims of subprime lenders, and started a 2008 Rescue Loan Program to help refinance mortgages. But as the financial crises deepened, loan losses accelerated. Precise data are not publicly available, but by the end of 2008 ShoreBank had increased its loan loss estimate to $42 million (vs. $6 million in 2007) and recorded a net loss of $13 million (vs. net income of $4 million in 2007).

The FDIC and Illinois Department of Financial & Professional Regulation took formal action to address ShoreBank’s deteriorating financial condition in 2009. In April, the regulators rated ShoreBank as a “problem bank.” (Their January 2008 ranking was “fundamentally sound.”) This led to a visit from state and regional FDIC officials and, at ShoreBank’s request, a meeting with FDIC officials in Washington, D.C. The parties entered into a consent decree—known as a “cease and desist” order—that was formalized on July 20. Loans were revalued downward, and the need for new capital grew.

Capital is to a bank what water is to a person in the desert—the key to survival. ShoreBank began raising capital by issuing shares of common stock to private investors in the first quarter of 2009. The bank initially needed $20 million, but as its situation worsened throughout 2009, capital needs were reassessed. By July 2009, the bank was seeking $50 million to $60 million; this was revised to $80 million, and then $100 million by the end of 2009.3

The capital campaign was by turns difficult and exciting. The challenge of raising money during the nation’s most severe financial crisis since the Great Depression was daunting. But progress was made. By May 2010, ShoreBank had raised $146.3 million from 53 investors. But private capital alone wasn’t sufficient in the nation’s new banking environment. The private funds were placed in escrow, contingent upon ShoreBank’s receipt of $72 million from the Treasury Department’s Community Development Capital Initiative (CDCI), part of the wider Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) initiative. In late 2009, President Obama approved extending TARP to cover CDFI banks, thrifts, and credit unions certified as targeting more than 60 percent of their activities to underserved communities.

As ShoreBank’s fundraising continued, a new management team was installed. On April 30, 2010, George Surgeon, longtime senior ShoreBank executive and CEO of ShoreBank’s banking operations since 2009, assumed the role of CEO of the entire holding company. At the same time, David Vitale, a highly regarded Chicago banking executive and civic leader, came on board to raise capital. The new leadership submitted ShoreBank’s CDCI application on March 1, a full month before the deadline, and on May 19 the FDIC’s Chicago Regional Office recommended that ShoreBank receive CDCI funds and forwarded the bank’s application to the FDIC’s Division of Supervision and Consumer Protection for further action. On May 26, ShoreBank Corporation announced further changes, bringing in a new executive leadership team to support Surgeon. Vitale became executive chair and a new president, chief operating officer, and CFO were announced—all of whom had successful track records in the mainstream banking industry. Grzywinski and Houghton officially retired.

ShoreBank’s situation was in public view, and a number of Illinois supporters, notably Rep. Jan Schakowsky (D-Ill.) urged the Treasury Department’s acceptance of the CDCI request. Rumors circulated that ShoreBank had “friends in high places,” particularly at the Obama White House.4 On May 21, television personality Glenn Beck set out to “expose” ShoreBank as something other than a “really good local bank.” He asked why Wall Street heavyweights such as Goldman Sachs were pledging millions to assist ShoreBank, insinuating political motives. Republican legislators openly questioned the administration’s support for ShoreBank at the same time new rules were being drawn for the financial services industry.5 The political temperature of the rescue escalated.

ShoreBank’s funding request required a review and vote by an interagency group representing the FDIC and other federal banking agencies. This CDCI Interagency Council considered ShoreBank’s request on May 26 and again on June 2—and, according to FDIC Inspector General Jon T. Rymer, deferred a vote both times because of concerns about asset losses and the bank’s ability to raise capital. Each time, the bank renewed efforts to reassure regulators. In early June a rumor surfaced that unnamed Federal Reserve Board staffers believed ShoreBank would need $300 million of additional capital to survive. Finally, on June 15, ShoreBank’s application was considered for a third time. The council remained divided: The FDIC recommended that ShoreBank receive CDCI funds, but representatives from the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, Federal Reserve Board, and Office of Thrift Supervision voted no. As a result, the application was not forwarded to the Treasury Department for further consideration. Without CDCI funds, the assembled private capital could not be released from escrow, leaving the bank severely undercapitalized. That settled ShoreBank’s fate—it would have to be closed.

From June to August, negotiations took place as to how ShoreBank would be closed. There were few bidders. Negotiations among FDIC officials, ShoreBank’s new officers, state regulators, and potential investors gave rise to the idea of creating a newly chartered institution to purchase the assets of ShoreBank—including banking operations in the Midwest, but not the other assets of the holding company. This became reality with the creation of Urban Partnership Bank, which was granted an application for deposit insurance and a state charter by Illinois on Aug. 16, 2010. Four days later, ShoreBank was closed by order of the state of Illinois and Urban Partnership purchased its assets.

Urban Partnership Bank currently operates as an FDIC-insured bank whose mission includes promoting economic sustainability and serving the needs of low- and moderate-income groups in Chicago, Cleveland, and Detroit. It is owned by the financial institutions, foundations, companies, and individuals that sought to continue ShoreBank. Twenty-two of the 53 investors, representing $139 million of the $146 million pledged to save ShoreBank, transferred their investments to Urban Partnership Bank. Three of Urban Partnership Bank’s current senior leaders were executives who had joined ShoreBank during the period of FDIC supervision and resolution.

LESSONS LEARNED

The closing of ShoreBank presents a fascinating set of puzzles for analysts. Conventional wisdom suggests that ShoreBank was a victim of simple economic realities: too little capital in the face of an unexpectedly deep recession. Some might argue that this shortage was caused, in turn, by ineffective risk management and a history of operating decisions that settled for a below-market return on investments. But we believe these arguments are flawed or, at best, incomplete. The bank needed capital, true, but so did hundreds of other US banks during the financial meltdown. The bank’s operating policies and risk management had succeeded for 35 years, through recessions and industry crises, and it was rated highly by regulators until the 2008 financial crisis. It responded well to the crisis, and the regional FDIC office recommended it receive CDCI funds.

Another possible analysis is that ShoreBank suffered because it was not seen as “too big to fail.” Had it been much larger, the federal government might have saved it from collapse. But the federal government was not concerned about smaller banks or banks that were socially beneficial, in other words, “too good to fail.” Had ShoreBank’s catalytic role in the communities it served been more broadly understood and accepted, it might have mustered the necessary political support for a rescue package.

A third possibility is that the interagency vote against CDCI funding for ShoreBank was a politicized vote. On May 14, Fox Business Network commentator Charlie Gasparino reported that Wall Street bankers “personally” told him there was “political pressure put on them to bail out ShoreBank.” No details were offered. The support of Democratic legislators and past contacts between ShoreBank executives with members of the Obama administration, including Senior Advisor Valerie Jarrett and President Obama himself, prompted Republicans to challenge the ShoreBank bailout. John D. McKinnon and Elizabeth Williamson reported in The Wall Street Journal on May 20, 2010—before the interagency votes—that questions raised by members of Congress about ShoreBank’s alleged use of political influence were greatly complicating its efforts to raise private capital from large banks and CDCI funds.

“Republican lawmakers began two inquiries into the rescue of a pioneering Chicago community bank by some of Wall Street’s biggest financial firms, saying political considerations appear to be at work,” McKinnon and Williamson wrote. “Goldman Sachs Group Inc. Chief Executive Lloyd Blankfein was personally making fundraising calls to other banking executives, seeking private sector pledges totaling $125 million for the failing community development lender, Chicago’s ShoreBank Corp. After initially declining to invest, Goldman itself promised at least $20 million in recent days.”

According to McKinnon and Williamson, on May 19, Rep. Darrell Issa of California, ranking Republican on the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, wrote a letter to the White House to complain. “It is important to avoid even the mere appearance that Mr. Blankfein is attempting to curry favor with the administration by contributing money to save the White House’s favorite community bank,” Issa wrote. In a second letter to President Obama, Republican lawmakers cited assertions by some bank representatives that the White House pressed them to contribute to the ShoreBank fundraising. Rep. Spencer Bachus of Alabama, the top Republican on the House Committee on Financial Services (a long-standing critic of community development banks), and Rep. Judy Biggert (R-Ill.) said the allegations “raised questions as to whether the government was rescuing a politically connected bank while letting hundreds of others fail.” 6

The ShoreBank story virtually defines the toxic politics of Washington today. Rather than spend $72 million, with the potential of repayment, to support a bank with a multi-decade track record of adequate liquidity and positive economic development impact—objectives favored by both Democratic and Republican administrations—the Deposit Insurance Fund has been saddled with a loss of more than $330 million. The reason? After ShoreBank was closed, the FDIC entered into a loss-sharing agreement with Urban Partnership Bank in which FDIC absorbed a large share of $329 million of losses to provide the new bank with a healthy balance sheet. (This estimate was revised to $452 million in January 2011.) Meanwhile, the investigation by Rymer, prompted by Republican members of Congress, concluded there was no wrongdoing by either ShoreBank or the FDIC. According to Rymer, the large investors in ShoreBank and Urban Partnership Bank invested “primarily because they believed in ShoreBank’s mission and they did not feel pressure to invest as a result of the FDIC chairman’s calls.” 7

Beyond this lesson in toxic politics, there are several big-picture lessons to be gleaned from the closing of ShoreBank. First, an organization’s social mission must be balanced with financial realities. A social mission should serve as a powerful incentive to strengthen an organization’s operating systems from the harsh consequences of the economy, competition, or a hostile environment. Clearly adequate for normal times, ShoreBank’s credit and risk management processes were not sufficient to withstand the full force of the financial meltdown. Concentrating most of its loans among low- and moderate-income people and businesses in inner-city Chicago, Cleveland, and Detroit fulfilled the bank’s social mission, but it also exposed it to significant risk during an economic downturn. The rapid deterioration of the bank’s assets and loan portfolios was magnified by regulatory resets, as loan portfolios had to be revalued downward with the deepening recession. This damaged the bank’s balance sheet and exacerbated the need for new capital. The lesson here is clear: For market-based social ventures, mission should be highly integrated with and responsive to the changing realities of the market.

ShoreBank also provides a cautionary lesson about new organizational models and resource limitations. There was genius in the idea of using a bank holding company to own and operate for-profit and nonprofit entities focused on the same social mission. And the founders’ passion for replicating the model and assisting others to learn from it was admirable. Like all experimental ventures, there were failures and successes and demands for ongoing learning and refinement. At the same time, legitimate questions remain about whether the resources of the holding company were sufficient for the breadth of its activities. Could ShoreBank have achieved the same results through partnerships with independent nonprofits rather than by housing them within the holding company structure? There is an argument for coordination and control through a holding company structure, but particularly in the new economy, there is a counterargument for more flexible, less burdened organizational models.

Lastly, did ShoreBank succeed in hiring enough new leaders—both strong in banking knowledge and passionate about the social mission—who could run the many pieces of the holding company? Operations in Cleveland and Detroit were disappointing, but the operations were not shut down. Should they have been? Could resources have been more effectively used elsewhere, in some of the more specialized lines of business that produced healthier financial and social impact? Experimentation is necessary and expected, but learning—and making changes, including some that are painful—is vital.

In the end, ShoreBank leaves an almost four-decade legacy of innovative ideas: It demonstrated that careful re-engineering of the market-based banking system can achieve adequate profitability and deliver strong social impact. ShoreBank also proved to be a catalytic presence in its community, in the banking industry, and throughout the world. We believe this is a dual legacy that matters and endures.

ShoreBank’s commitment to progressive banking lives on in the community development banks it inspired and, more directly, in the Urban Partnership Bank, whose mission is closely aligned with what ShoreBank’s once was.8 ShoreBank Pacific lives on through OneCalifornia Bank (now One PacificCoast Bank) and ShoreBank International is now a leading financial advisory firm. Last, many of the nonprofit entities now operate as independent nonprofits (mostly under revised names) and continue their original missions of aiding economic development through investment, research, and consulting services.

Taken together, ShoreBank provides an important lesson about value creation that is social in nature. In late 2008, Grzywinski said that although ShoreBank had failed to prove that a broader social usage of capital was an idea whose time had arrived, “certainly it was an idea we think is on the right side of history.” Indeed, the world needs radical, more effective, scalable approaches to address social problems. These will come only from those who are willing to operate in uncharted territory. Innovative organizations like ShoreBank, which harness the capitalist system to produce positive social outcomes, continue to offer promise for the future.

ShoreBank was never perfect, but it was too good to fail.

James E. Post holds the John F. Smith, Jr. Professorship in Management at Boston University. He is co-author of Redefining the Corporation: Stakeholder Management and Organizational Wealth. In 2010, he received the Aspen Institute Faculty Pioneer for Lifetime Achievement Award in the field of business and society.

Fiona S. Wilson is assistant professor of strategy, sustainability, and social entrepreneurship at the Whittemore School of Business & Economics at the University of New Hampshire.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by James E. Post & Fiona S. Wilson.