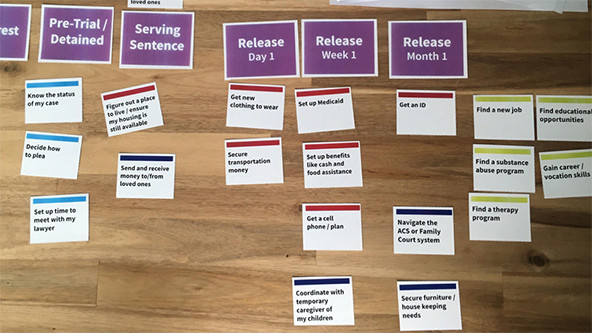

A card-sorting activity used in one-on-one meetings with women who experienced the criminal justice system prompts them to list out and talk through what was on their mind at different moments in the process. (Photo by Emily Herrick)

A card-sorting activity used in one-on-one meetings with women who experienced the criminal justice system prompts them to list out and talk through what was on their mind at different moments in the process. (Photo by Emily Herrick)

In the United States, the criminal justice system is one of many public institutions whose workings span multiple jurisdictions. If you’ve been arrested and served jail time, it’s not uncommon to interact with more than 10 different organizations in the process. These often include federal, state, and local government entities; nonprofits; and private institutions. Moving through this system can feel like a series of detached actions and reactions, and impede even straightforward tasks, such as contacting a public defender.

Each institution within the system is unique and dynamic. The people, processes, and political realities at different organizations don’t always work together, and differing priorities and timelines can lead to lost opportunities. When someone enters a correctional environment, for example, they go through a screening and intake process. Corrections departments see this step as an opportunity to assess whether someone may harm others or themselves. Social service providers, on the other hand, see it as a moment to determine people’s needs, goals, and aspirations, and to connect them to rehabilitative programming like therapy or substance abuse treatment. If the two entities don’t agree on an intake method that serves both—for example, conducting a comprehensive needs assessment at the moment of entry—it’s difficult to connect people to reentry services at all.

These barriers and limitations negatively affect everyone who experiences them, and like other fundamental criminal justice operations, the process needs to change. The important and widespread social movements currently demanding that the system address institutional racism are well-aligned with the vision we have for our own work on tackling this service fragmentation: to transform the system from one that is unfairly and unnecessarily punishing to one that is restorative, by inviting those with lived experience help chart the course.

Focusing In on Women

In 2018, Chirlane McCray, first lady of New York City, called attention to the fact that women in jail have a unique set of needs from men. Many are mothers and primary caregivers, for example, and compared to men, many experience harsher stigma from their support networks after being arrested. In addition, nationally, the incarceration of women is growing at twice the rate of men.

Are you enjoying this article? Read more like this, plus SSIR's full archive of content, when you subscribe.

To help address these needs, McCray created the Women in Rikers initiative, which supports gender-responsive programs for women experiencing incarceration. Programs include reentry services focused on promoting healthy connections between children and families, acknowledging mental health and substance abuse needs, healing from trauma related to the systemic injustices of poverty and institutional racism, and healing from deeply personal trauma related to assault or intimate family violence. The initiative—coupled with the city’s work on bail reform, alternatives to incarceration and detention programs, and housing and mental health support—has led to a decrease in the rate of women’s incarceration and the overall reduction in jail population.

As part of the Women in Rikers initiative, the city engaged our team at the Service Design Studio at the Mayor’s Office for Economic Opportunity. Funded in part by Citi, our projects aim to make public services more accessible and dignified by designing alongside the people who use them. We began to explore how New York City might improve access to reentry services for women leaving municipal jails, and went on to work with more than 30 women, nearly 15 frontline staff, and countless service providers involved in the criminal justice system.

Having experienced jail first hand, the formerly incarcerated and incarcerated women we spoke with shared important insights that grounded and guided our reimagining of the reentry experience. We learned, for example, that when mothers are arrested, it’s often difficult for them to contact loved ones before arriving at the jail. Because they lose access to their cell phones on arrest—and, like all of us, rarely memorize phone numbers—they have no way of immediately contacting their children, or arranging for a friend or family member to pick them up from school. There’s also no established channel for frontline staff or mothers to recover those numbers themselves, or ask someone for help.

Once admitted to jail, these women face other uncertainties and challenges. For the most part, those in jail are awaiting trial and have not been convicted of a crime. This wait time is sometimes unknown. When someone’s court date arrives, authorities wake them up, often when it is still dark outside, and bus them to a courthouse. There, they may wait hours before meeting with a public defender and then testify in front of a judge. They may be advised to take a plea deal they don’t fully understand, which can later result in difficulty getting a job or benefits. If found innocent, they may be released directly from the courthouse in their jail uniform, with no identification or phone.

Finally, there’s life afterward. Those who await trial for long periods of time may lose their apartment or other critical resources in the interim. Many women who have experienced domestic violence don’t have a safe place to go after they’re released. What’s more, a high percentage of people in local jails, regardless of gender, struggle with addiction. Getting abruptly released from the courthouse also makes it incredibly difficult for people to take the first step of accessing reentry programs that offer supportive housing or rehab.

These stories highlight the gaps within the criminal justice system and the need to design a new system that is restorative, rather than unnecessarily punitive.

Co-Designing a Better Reentry System

While the idea of co-creation in government isn’t new, it’s still far from the status quo. Most civil servants are much more comfortable delivering new programs to constituents than asking constituents how they might design something better. Co-design therefore requires a cultural shift within agencies; more agencies need to be comfortable with ambiguity and deeply question the expansive, layered systems in which they operate.

Women affected by the criminal justice system give feedback on paper prototypes of an intake screening. (Photo by Shannon Straney)

Women affected by the criminal justice system give feedback on paper prototypes of an intake screening. (Photo by Shannon Straney)

Following our interviews, we facilitated a co-design process to reimagine the reentry infrastructure—including technology, staff roles, and information sharing protocols—so that it met the specific needs and desires that affected women identified as priorities. Our approach borrowed evidence-based best practices from literature on reentry programming and trauma-informed care, and pulled in methods from design research, social work, community engagement, and human-centered design.

Using tools like Lego Serious Play, Appreciative Inquiry, collaborative journey mapping, and rapid prototyping, we asked women to imagine better alternatives to what they experienced. Together, we developed a series of concepts focused on moving reentry planning earlier in the jail experience, and streamlining how women request and get matched to reentry providers.

We also led a series of workshops with professionals working on all sides of the criminal justice system, including correctional officers and social workers working inside the jail, and reentry staff in the communities women returned to after their release. In the workshops, we defined current staff roles and responsibilities, matched women’s priorities to staff workflows, and began brainstorming tools and permissions staff would need to make our ideas a reality.

Because most agencies in the criminal justice system are risk-averse, we knew we’d have to try solutions out to see if they worked before passing them up the chain. We synthesized our learnings into three digital prototypes to meet the needs we heard from women and their social workers. These included:

- A client-driven needs assessment that helps women prioritize their reentry needs

- A customizable guidebook to help women navigate jail and trial processes

- A referral management system to help staff identify and coordinate the programs and services an individual is eligible for

As we made these prototypes, our goal was to build tools that worked just well enough to demonstrate the different concepts and show what the future might look like. This “Wizard of Oz” form of prototyping allowed us to have concrete conversations with women who were either in or recently released from jail, as well as social service staff, about possible improvements. They raised important implementation and viability considerations early on, before agencies spent time or money on rolling out system-wide solutions.

Through these conversations, one thing became certain: Most jail environments currently lack Wi-Fi but desperately need it before they can function better. In many cases, for example, social workers visit multiple housing units and are tasked with handling requests from women. For instance, someone might request that their social worker call their child welfare caseworker to let them know they can’t make an upcoming appointment. We heard from support staff that they record important and timely requests from women who have been arrested on slips of paper, but can’t digitally record or act on them until hours later when they are back at their desks.

Despite the fact that the viability of all our prototypes depends on Wi-Fi and they can’t yet be implemented, they played an important role in making progress. Without them, we would not have been able to have concrete conversations with people who have experienced the system or identify where change needed to start. Since meaningful change in large systems happens incrementally, we believe a first step toward operationalizing the visions of the staff and women we talked to is to install Wi-Fi in jail environments. From there, other changes can build. Going back to the example above, if social workers can eventually coordinate needs and requests on tablets from anywhere, women experiencing the system will have that much more access to reentry support.

Designing in Harmony

When done well, co-design can generate new opportunities and help allocate resources more effectively, but creating co-designed prototypes and implementation recommendations is only half of the equation. To make system improvements that span typical organizational boundaries—for example, between state and city jurisdictions, or courts and jails—civil servants need to: a) form deep working partnerships that cross typical agency silos, and b) convince decision makers to support solutions that emerge during the co-design process. This can be difficult, especially within high-stake, risk-averse environments like the criminal justice system.

While we certainly don’t have all the answers, we believe governments can do more to align priorities and connect efforts across systems. Taking stock of how people experience and use existing systems reveals partnership gaps and opportunities. And empowering our residents and front-line staff as creators and decision makers can surface integrated solutions and nuanced policy recommendations. Both of these steps require thinking beyond agency mandates.

In the human body, the heart and brain have separate functions but work together. We believe this same kind of alignment is possible in government when we put the people that use and deliver public services at the center of our design and delivery processes.

This essay was produced in partnership with Apolitical. It was selected as the winner of Apolitical's 2020 American Public Servant Writing Competition, which explores untold stories of change in American government.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Emily Herrick & Caroline Bauer.