Record-breaking heat and hurricanes. Refugees with no place to go. Increasing income inequality in some of the world’s wealthiest countries. At the roots of these tremendous problems are a tangle of causes that demand massive, coordinated action from a multitude of actors—they demand social innovation at scale.

Given the urgency and intensity of today’s social problems, funders are eager to discover proven solutions that can be quickly implemented and scaled up. Inspired by the technological tools and rapid-fire timelines of our era, many funders are looking for the Airbnb or Facebook of social innovation. Unfortunately, there’s a tremendous gap between the expectations of funders and the reality that innovators and changemakers face each day. The resources, ecosystems, and prospects for growth at a company like Facebook are vastly different than those available for those who work on social innovations like microfinance and emissions trading. (For more analysis of how microfinance and emissions trading scaled up, see these two case studies.)

Our goal was to understand the patterns that enable social innovations to scale up. We drew from research and practices over the past decade at Stanford University’s Center for Social Innovation; at SI-Drive, a European Union-based initiative to advance social innovation on a global scale; and at Tides, a philanthropic partner and nonprofit accelerator that works with funders and changemakers across the world.

We studied the emergence and scaling up of ten social innovations that have shifted the status quo for society’s benefit rather than individual gain. (The definition we use for social innovation is a novel solution to a social problem that is more effective, efficient, or sustainable than existing solutions and for which the value created accrues primarily to society as a whole, rather than to private individuals.)

Are you enjoying this article? Read more like this, plus SSIR's full archive of content, when you subscribe.

Each innovation traversed a different path to reach exponentially more people and expand to new geographies. We studied the challenges and inflection points as each innovation built momentum and identified three barriers that prevented them from scaling up. We found that these barriers were most troublesome between the piloting phase and the scaling phase of a social innovation’s evolution, creating what we call a “stagnation chasm,” where proven ideas get stuck before they are able to maximize their impact.

This article is a call for deeper analysis, understanding, and action to overcome the barriers that stunt proven social innovations from reaching maximum impact. Although there is no universal formula and no one has all the answers, we as a field have more knowledge than ever before. We have more data, deeper insights, and richer case studies to inform our work. The field continues to grow with an ever-expanding circle of changemakers, funders, and partners noticing what works and what doesn’t, and exchanging lessons learned.

By proposing the stagnation chasm as a framework for understanding needs in the field, highlighting promising solutions, and suggesting steps forward, we hope to encourage additional research and on-the-ground experimentation among funders who seek to increase the pace of progress toward a more just, sustainable, and prosperous world for everyone.

What Do We Mean by Scale?

There isn’t a universal definition of scale. Duke University’s Center for Advancement of Social Entrepreneurship has proposed that “social innovations have scaled when their impact grows to match the level of need.” Jeffrey Bradach, managing partner and co-founder of The Bridgespan Group, provides an alternate perspective on scale: “How can we get 100x the impact with only a 2x change in the size of the organization?”

By design, we did not set a precise definition of scale in our research, because we wanted to explore the factors that had been important for a broad range of social innovations to achieve widespread impact over the past 30 years. Scaling impact can look different for different innovations.

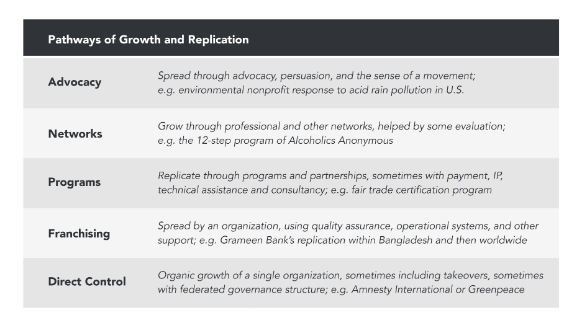

Geoffrey Mulgan has created a valuable tool for understanding the unique and varied paths that social innovations take as they scale up. He identified five pathways to scale, which we have summarized below: advocacy, networks, programs, franchising, and direct control.

Our research affirmed that scaling up a social innovation to achieve deep and sustained impact often entails an assortment of the strategies listed above, employed thoughtfully over a long time to build momentum, support, and widespread adoption.

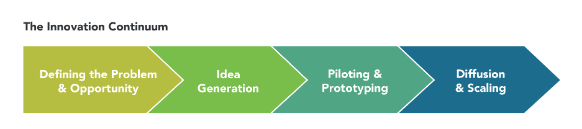

Moving from identifying a problem to scaling up a solution is what we call “the innovation continuum.” This model helps us to identify the needs, opportunities, and strategies most critical at various points in a social innovation’s trajectory.

As we applied the innovation continuum to the cases we studied, we identified barriers to scale that often trap social innovations in a stagnation chasm before they achieve diffusion and scaling.

Three barriers in particular repeatedly block social innovations from reaching their broadest impact: inadequate funds for growth, the fragmented nature of the social innovation ecosystem, and talent gaps. If we are serious about propelling proven social innovations to achieve widespread impact, we must find solutions that overcome each of these barriers. The rest of the article will explore in more detail each of these three barriers in turn.

1. Inadequate Funding

Social innovators face a convoluted and often elusive path to mobilize the resources needed to amplify the impact of their work. Of the strategies for scale in Mulgan’s typology, some are very capital intensive, others less so. Yet even the advocacy and network approaches to scaling social impact require resources. It takes time, funding, and expertise to navigate the relationships and complex interdependencies that are critical to success. Some ventures may benefit from earned revenue streams that provide funds for growth, but earned revenue isn’t guaranteed in the social innovation space, especially for innovations that operate where markets fail to meet needs and serve people with no ability to pay. Thus, external funding is usually needed in order to scale impact, whether from donors or from investors depending on the legal structure and financial prospects of the venture.

An analogous struggle occurs in for-profit entrepreneurship: the so-called “valley of death” refers to the time between a start-up company’s first funding and when it begins to generate revenue. In the valley of death, the firm is vulnerable to cash flow requirements and likely to fail before it has reached its full potential. The for-profit ecosystem culls bad ideas early, and most companies do not make it across the valley of death. Once a company has crossed the valley of death, however there is a well-developed progression of funding, with various sources of capital that enable companies with high potential for profitability to scale.

For social innovations, the progression of funding is vastly different. Mezzanine funding and growth capital are hard to come by, and scarce resources often stall proven solutions before they have the opportunity to achieve their full potential. To overcome the stagnation chasm, social innovations need access to capital similar in size and staging to that which fuels growth in the private sector.

Social innovation funders are often drawn to the early stages of the innovation continuum marked by idea generation and prototyping, and myriad incubators and accelerators have emerged to support these stages in the innovation process. But preparing to scale increases organizational costs, as investments are needed to upgrade technology, hire senior-level talent, and improve infrastructure. However, these critical activities rarely produce immediate results and can be less appealing to funders.

Despite the promising emergence of impact investing, market forces do not push mainstream capital toward social innovations, as the promise of market rate financial returns can rarely compete with traditional industries. Given the short-term profit incentives of most investment capital, many social innovations require philanthropic support.

And philanthropic funders struggle to align their expectations with the long-term nature of social innovation. We know that social innovations face tremendous barriers: ups, downs, and detours are to be expected in pursuit of impact. Yet it is rare for funders to make long-term (five to 20 year) commitments and sustain their support over time. Many philanthropists, particularly new ones, have had successful careers in the private sector and bring expectations for market-driven efficiencies that are not realistic when working in troubled economies, with marginalized people, or on issues where market forces hinder rather than help drive desired behaviors.

Funding social innovations to reach scale requires an unwavering commitment to the end goal and a great deal of patience and flexibility. To strengthen the financial landscape for scaling social innovations funders should consider doing the following four things:

-

Increase funding amounts to support growth and diffusion. Most investments and grants range from $50,000 to $500,000, yet building infrastructure, hiring teams, replicating a model, or developing complex collaborations requires much more money. We see promise in new funding approaches that are emerging. Some governments are investing in social change, through initiatives like the USAID Skoll Innovation Investment Alliance and EU Horizon 2020. Private foundations, such as the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and MacArthur Foundation’s pilot 100&Change initiative, are making sizeable investments focused on scale. And funding collaboratives, such as Blue Meridian Partners and Co-Impact’s community of philanthropists, are providing new and increased funding sources to bring social innovations to scale. More bold moves and big bucks are needed.

-

Act as a partner, not just a funder. In the nonprofit sector, funding is usually provided on one- to three-year terms, occasionally for five years, and rarely longer. The reality is that social innovations take decades to refine, build traction, and grow. Funders need to dig deep to develop unwavering commitment to the issues that matter to them. Rather than the traditional funder-recipient relationship, which can feel like a transaction of funds for results, funders and innovators should set an impact goal together and commit to being long-term partners in the journey to crack very tough problems. Over time, the funding relationship should evolve and deepen through mutual learning, support, adaptation, and persistent pursuit of impact.

-

Provide funding for overhead expenses. Some years back, overhead expenses became associated with bloated and ineffectual organizational management, and overhead rates were highlighted as a short-cut indicator of organizational efficiency. This is a fallacy. Competitively paid staff, effective management systems, and strong infrastructure often correlate with impact. For example, organizations with pioneering technology may require a CTO, and organizations with significant scale may need a CFO to provide proper financial vision and oversight. A healthy cash reserve is also important to ensure stability and sustain operations through the fits and spurts of growth, but most funders don’t want to contribute directly to a reserve. We must avoid starving the organizations we fund in pursuit of efficiency or tying up all funding for restricted programmatic use, which can feed into what has been called a “starvation cycle.” Rather, by investing in organizations and ideas over the long term through general support and paying for the full cost of impact, foundations will position nonprofits for greater impact and growth, increasing the likelihood that they can cross the stagnation chasm.

-

Take informed risks when deciding who and how much to fund. When proven social innovations (and the organizations and people carrying them forward) see opportunities to scale, the stakes rise dramatically. Small grants and trickles of earned income aren’t enough to fuel most strategies for scale. Yet to double down with increased investments of both financial and reputational capital can be risky, especially in an ecosystem that hasn’t developed expectation norms for some losses in order to get a big win (as has the for-profit ecosystem). Foundations face a fork in the road; the safe play is to continue business as usual with smaller, early-stage, or sustaining grants, which yield gradual but rarely break-through impact. The bold move is to seize opportunities to shift the status quo and go big through major investments when the opportunity for impact requires it.

Understanding the barriers to this tier of funding, learning from social innovations that have successfully mobilized growth capital, and applauding the leadership of forward-thinking funders will help deploy resources so that proven innovations are able to scale up their impact. The scarcity of funding for growth is a primary cause of the stagnation chasm, which is exacerbated by fragmented ecosystems and the talent gap in the sector.

2. A Fragmented Ecosystem

One sector toiling in isolation or digging into an adversarial approach cannot achieve breakthrough scale on its own. Instead, engaging and coordinating actions across various actors from the private, nonprofit, and public sectors is critical. In the case of microfinance, for example, the innovation garnered interest from government and business when nonprofits like Grameen Bank had demonstrated success in providing financial services to formerly unbanked people.

Following the pioneering role of nonprofits to establish proof of concept, commercial banks entered the market, with mixed social outcomes, given the pressure they faced for profitability. As the microfinance industry matured, governments created a legal and regulatory environment that encouraged transparency, market entry, and competition. The cumulative efforts and engagement across the nonprofit, private, and public sectors were critical to scaling microfinance as we know it today and will continue to refine the approach for better social outcomes in the future.

Unfortunately, the complexity of multi-sector collaboration, and the reality that such collaborations are often critical to scaling social innovations, impede many social innovations from widespread impact. No matter what the issue—health, environment, or education—once a multi-sector approach is employed, the ecosystem complexity multiplies. Each sector has its own set of resources, rules, incentives, knowledge, and networks. Mutual awareness is low, and meaningful coordination is even more uncommon. Current incentives do not encourage collaboration, and few organizations are positioned to weave together efforts, resources, and activities from all three sectors to drive social innovations toward impact on a broad scale.

To strengthen opportunities for collaboration across sectors and create a more catalytic ecosystem for scaling social innovations, social innovators should consider doing the following three things:

-

Build relationships in all three sectors. Opportunities to generate solutions often emerge along the margins of overlap between sectors where traditional silos break down, insights are shared, and innovation is sparked. Environmental nonprofits such as Sustainable Conservation and Environmental Defense Fund, for example, achieved break-through environmental regulations by understanding the needs of industry representatives. It’s not uncommon for nonprofit leaders to attempt to engage corporate interests or government entities; however, doing so successfully is rare because it is hard. To increase impact from cross-sector pollination, funders also need to engage with unlikely partners and actively seek out different perspectives, including both government and the private sector. We know of no foundation that has an executive position focused solely on corporate partnerships or government relations, yet philanthropic leaders possess strategic autonomy and financial freedom that can be mobilized in innovative ways to drive change on the ground.

-

Increase support for “bridgers” to develop cross-sector fluency. Career paths in social innovation are not linear or bound by a single company or sector for the duration. High impact leaders and staff often pinball between sectors during the course of their careers, developing experience and fluency to operate effectively in structures and with actors in civil society, the private sector, and the public sector alike. Equipping future organizations for this work requires us to stretch beyond traditional academic and post-graduate educational pathways. Most social innovation programs and accelerators focus on developing leaders to run early-stage start-ups. To get innovations to scale, we must design new programs for leaders and organizations to build their bridging capacities. As more people and institutions develop such experience, they can knit together disparate systems and pioneer collaborations that propel social innovations to scale.

-

Fund partnerships and collaborations. Collaboration does not happen by accident. It takes time, resources, and expertise to knit together individual efforts in service of a shared goal. Funders have a critical role here to support the breadth of work that drives successful collaboration over time. At organizations seeking to collaborate with unlikely partners, entire teams need to have the mindset, vision, and skills to work across sectors. To improve the efficacy and efficiency of collaborations requires support for the staffing and work required to build alignment around end goals, surface and strategize around new ideas, mutually determine short-term tactics, and follow-through on the complex process of implementation.

Upholding all systems within each sector are people who are working within the bounds of the expectations and opportunities that surround them. To bridge the stagnation chasm, we must think differently about how we develop the people who can overcome these challenges.

3. The Talent Gap

To drive social innovations in a world of rapid change, organizations need talented leaders supported by effective teams. The insufficient funding and fragmented ecosystem require highly adept people to shepherd social innovations through the long journey to widespread social impact. Unfortunately, attracting and retaining people to navigate these complexities is a challenge.

The leadership skills required at the beginning of a venture are very different than what’s needed to cross the stagnation chasm. Personal charisma and resourcefulness serve an entrepreneur well in the ideation and piloting phase, but as an innovation matures, more specialized skills are required to build a powerful team, manage an expanding board of directors, and broker and sustain successful partnerships. Systems thinking becomes more actionable as innovations develop, requiring expertise in advocacy and policy. Moreover, as the organization scales, so does the operational complexity in terms of human resources, supply chains, and infrastructure. This requires a management team and staff with deep functional and technical expertise who thrive working in complex ecosystems.

To strengthen the pipeline of leaders, management, and staff prepared to take social innovations to scale, organizations involved in social innovation should consider doing the following three things:

-

Invest in teams, not just CEOs. Social and environmental challenges are typically more complex and entrenched than the business objectives of most commercial ventures. Indeed, ensuring a clean and sustainable water supply in a town in India can be more difficult than producing and marketing a canned beverage. Yet the teams working to create change are vastly smaller and comparatively under-resourced. The social innovation field needs to improve its training, compensation, retention, and professional development for teams—extending beyond the CEO—so that mission-oriented teams can take on this critical work, cultivate the skills they need, and sustain their energy and commitment to impact over time.

-

Cultivate advanced managerial and systems-thinking skills. We need to build on current programs that incubate and accelerate mission-driven start-ups to address the needs of mid-size and growing organizations. In a rapidly changing world, managing complex systems and data presents both challenges and new opportunities for impact. Furthermore, skills in systems-level thinking, designing partnerships, strategies for scale, and thought leadership become increasingly important, since the key to scale is often whether or not a social innovation can move beyond helping people in a specific community to also shape mainstream business practices or ally with government. Resources to support leaders and their teams to develop the higher-level skills to engage with government and private sector collaborators are scarce yet vital.

-

Boards of directors need to adopt new skills and mindsets. To shift organizations toward impact at scale, organizational governance also needs to change. Board obligations to fiduciary responsibility and mission stewardship are not enough, because moving an innovation toward scale requires bold vision, dexterous relationship building, and pragmatic know-how. As with the leadership team, the skills and expertise of board members at the scaling stage need to evolve toward systems thinking, cross-sector collaboration, and growth. Board members are uniquely equipped to network across sectors, watch for shifts in the broader landscape, bring in new funders, encourage organizations to take informed risks, pioneer new partnerships, and craft high-impact collaborations to grow impact.

As a field, we need to develop a deeper understanding of the leadership skills needed for leaders and organizations to coordinate with each other in order to collectively push social innovations across the stagnation chasm. These insights will strengthen our approach to human capital development to better equip leaders and their teams to advance proven social innovations at scale.

Where Do We Go from Here?

To tackle large social problems we cannot be intimidated into working at the fringes or allowing ourselves to feel satisfied with small steps forward. We need big leaps for humanity and for our planet to address issues like climate change and the impact of technology on the labor market. We are equipped with more information and material resources than ever before in history.

Now is the time to apply our tools, our will, and our vision to enable bold advances that redefine what’s possible. Social innovation has moved from an emergent field to become a global phenomenon, with myriad universities building knowledge, the European Union’s SI Drive sparking a global exchange of learning, and researchers and funders across the planet positioned to accelerate impact. Here at Tides—working at the nexus of funders and changemakers—we are eager to build on the momentum surrounding social innovation so that we can leave our world more just, prosperous, and sustainable than we found it.

The opportunity for impact mirrors the immensity of the need. This can be done. We have learned that for-profit innovation grows in countries with strong innovation systems, which include financial, managerial, technical, and other support for entrepreneurs and ideas. To create vibrant social innovation systems we must nurture a global ecosystem that can support the social innovation process from ideation all the way through scaling, so that the promise of proven solutions can reach the people and places most in need.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Kriss Deiglmeier & Amanda Greco.