(Illustration by Hugo Herrera)

(Illustration by Hugo Herrera)

For decades, nonprofits, governments, philanthropies, and corporations have been dogged by how to measure social impact. Many say the challenge is near-impossible: Every social intervention is customized, every beneficiary is unique, every context is different, data is biased, self-reported data is unreliable, there are no measurement standards, and proving causation is problematic. Every nonprofit is left figuring out its own way to measure and report impact. And every funder is left wondering who and what to trust.

Laissez-faire is never a good thing when it comes to data. As one Scientific American contributor put it: “Crude data is similar to crude oil—in its raw form, it’s usually too messy to be useful.”

Do-it-yourself measurement certainly is not good for cash-strapped nonprofits, who are drowning in data. It’s not a good thing for donors, who have no way to ascertain the impact of nonprofits and can’t generate meaningful insights. And it’s not a good thing for the beneficiaries, whose voices are often not factored in. The only stakeholders who seem to be benefitting are the evaluation consultants, who profit greatly from what some refer to as an “evaluation-industrial complex.”

Other Sectors Have Figured It Out

The social sector is not the first sector to grapple with measurement—fields like health care, genetic research, and climate change share similar complications: highly differentiated participants, infinite combinations of interventions, complex outcomes, and lots of exogenous variables. The difference, however, is these fields have found ways to standardize data, track outcomes, and analyze results. All three fields have created a standardized database—or a registry—that all but eliminated the challenges of measurement.

While there are a number of potential purposes for registries, there are four major functions that they all share: (1) cataloging information, (2) reporting results, (3) determining impact and/or cost-effectiveness, and (4) analyzing what works.

The social sector has figured out how to do the first one well. We have databases like What Works Clearinghouse and Blueprints for Healthy Development that compile lists of independent studies on nonprofits and social programs. However, these resources, while useful for understanding potential impact, don’t quite provide a standardized way to measure, catalog, verify, or benchmark program performance in the real world.

In almost every sector that has used one, the adoption of a registry led to better outcomes. These structured repositories of data allow for ongoing data collection, modification, and retrieval in a standardized way, in turn enabling better research, benchmarking, prediction, and verification efforts sector-wide.

To illustrate, here are three examples of registries as they work in those different sectors: health care, genetic research, and climate change.

Health Care: Patient Registries

What it is: A patient registry captures all clinical data to help evaluate and improve outcomes for a population defined by a particular condition, disease, or exposure. There are many, but a good example is the North American Registry for Care and Research in Multiple Sclerosis (NARCRMS) which contains patient data for close to 1,000 Multiple Sclerosis (MS) patients. Structured data is entered into the registry to allow physicians to track the incidence, prevalence, and longitudinal history of MS over time.

How it works: Clinicians or researchers use observational study methods to collect uniform information (i.e., common data fields and definitions) about patients’ health status and the care they receive over time. This allows for the aggregation of large data sets to analyze trends or patterns in treatments and outcomes across the population.

How it’s helped: Easy access to clinical, genetic, and radiological data, and various biomaterials have helped develop biomarkers for MS. These biomarkers make it easier to diagnose, develop a prognosis, and respond to the progression by modifying therapies and managing side effects. It also helps research centers collaborate and share data as they become available, thus making it easier for research to address specific unanswered questions about MS.

Genetic Research: DNA Registries

What it is: Perhaps the most well-known DNA registry, 23andMe, is another great example. The premise is simple: citizens submit a saliva sample and get a report of their ancestral history after an analysis of their DNA. 23andMe calculates “ancestry composition” by comparing your genome with their reference dataset of over 14,000 people.

How it works: A DNA sample is put through the genotyping process which looks at hundreds of thousands of specific protein locations known to vary between individuals or associated with certain conditions, traits, or ancestry. The reference dataset consists of people with known ancestry, generally those who reflect populations that existed before transcontinental travel and migration were common. They also draw from public reference datasets, such as the Human Genome Diversity Project, HapMap, and the 1000 Genomes Project.

How it’s helped: Only through having such structured and standardized information available can 23andMe provide an ancestral history to customers. There’s also work to begin using the data to make dietary and health care decisions as well as solve current crimes and cold cases.

Climate Change: Carbon Registries

What it is: The Verra Registry was launched in April 2020 and is the cornerstone for the implementation of the Verified Carbon Standards, which ensure the credibility of emission reduction projects. It facilitates the transparent listing of information on certified projects, issued and retired units, and enables the trading of units. It is the central repository for all information and documentation relating to Verra projects and credits.

How it works: Carbon offset registries track offset (i.e., emission-reducing) projects and issue offset credits for each unit of emission reduction or removal that is verified and certified. Registries record the ownership of credits by assigning a serial number to each verified offset credit. When a credit is sold, the serial number for the reduction is transferred from the account of the seller to an account for the buyer. Once the buyer uses the credit, that serial number is retired so that the credit can’t be resold.

How it’s helped: Carbon registries help environmental project developers get carbon credits by collecting, verifying, and tracking outcomes. The registries perform other functions too, including certifying carbon offsets and enforcing specific guidelines for their verification and validation.

Why Registries Work

At their core, all data registries share the same goal: standardizing data to improve outcomes. In each sector, the underlying mechanics of a registry are based on consistent, structured data being reported into a centralized database according to strict protocols. Data can be self-reported or through a formal survey. Registries can also use observational study methods to collect and harmonize data about the treatment, outcomes, and well-being of clients or recipients who engage in the program over time.

Medical data registries have set the standard. Researcher Brian Drolet, in a 2008 article titled “Categorizing the world of registries,” laid out a framework for the evaluation and categorization of registries and other data systems and defined five distinguishing features of registries:

-

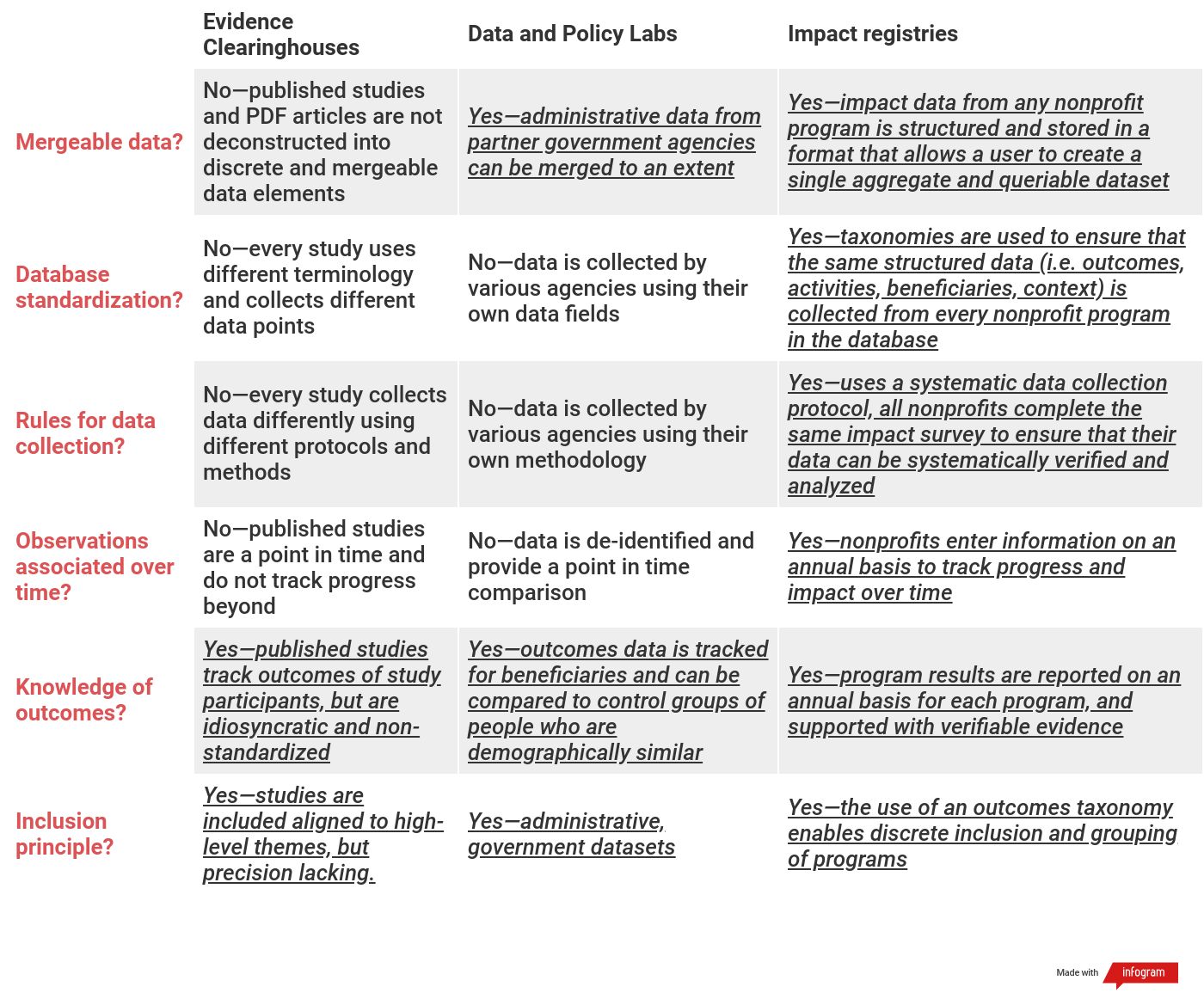

Mergeable data: Data is stored in a format that allows a user to create a single aggregate and queryable dataset for research and patient care purposes.

-

Database standardization: The same data are collected for all patients/records in a registry.

-

Rules for data collection: A set of characteristics are defined prior to the collection of data. These data are collected in a systematic manner.

-

Observations associated over time: The database is designed so that each patient is identified in the registry as a single continuous record for storage of longitudinal data.

-

Knowledge of outcomes: Follow-up must be obtained to assess outcomes or manage patient care.

This “MDR-OK” protocol is heavily dependent on data standardization.

The mechanics of a registry are straightforward: First, a registry starts with a specific purpose, such as to aggregate, benchmark, evaluate, and/or analyze what works. Next, a registry needs to capture data elements with specific and consistent data definitions. That means using standardized language for the key concepts, even if those concepts are more complex in nature—like DNA, carbon emissions, or medical intervention. All data should be collected in a uniform way for all participants, both the types of data collected and the frequency of their collection. Lastly, registered data is most valuable when it is validated and independently verified using strong evidence and solid calculations.

A Registry for the Social Sector?

In the social impact sector, our lack of standardized program data has meant it is difficult to tell whether the billions spent on social programs achieve their promised outcomes. That makes it difficult to drive social change on a significant scale, which is a big problem. If we really want to change the world, we have to find a way to solve social problems more efficiently. The creation of an impact registry for the social sector will enable the same data-driven approach that has transformed other sectors.

We’re getting close. Clearinghouses and data labs are two good starting points for harnessing the power of social sector data.

-

Evidence clearinghouses such as U.S. Department of Education's What Works Clearinghouse, Blueprints for Healthy Youth Development, Cochrane Collaboration, provide lists of reviewed and rated programs and interventions that meet specific criteria set by the clearinghouse.

-

Data labs and policy labs such as Gov Lab, Data Justice Lab, Washington State Institute for Public Policy, The Rhode Island Innovative Policy Lab, Actionable Intelligence for Social Policy, help to stratify and assess data so that it can be used to make comparisons, determine ROI, and improve outcomes.

Each of these initiatives has made positive steps in the right direction, collecting and centralizing data, consistently coding information, and creating applied use cases for research.

But an impact registry goes further by focusing on data standardization and independent verification of standard outcomes in a specific impact area (i.e., education, criminal justice, public health, etc.). To be truly comparable, program data in a database must be consistently collected and reported in the first place. Impact data in particular has been difficult to standardize without common taxonomies across programs working toward the same outcomes. And without independent verification, data that is reported into a registry won’t be as reliable and useful.

Over the past seven years, I have been part of a team of researchers working on a publicly-funded effort to create the sector’s first impact registry. It’s called the Impact Genome Project. Our process is intuitive, quick and doesn’t require deep technical knowledge. First, organizations provide information about their program and identify the relevant outcomes that match standardized outcome definitions. Then, the program submits their results along with supportive evidence. Finally, trained evaluators review the evidence and certify the impact claims.

The benefits of an impact registry, be it ours or one developed by others, could be transformational.

Imagine:

-

Impact “DNA” analysis: Researchers can use data in the registry to study different programs and pinpoint which characteristics are found in the overwhelming majority of successful and efficient programs, as well as which program characteristics may not lead to program success or actually hinder it.

-

Benchmarking: Nonprofit leaders or funders can benchmark the cost of social change in different outcome areas, then compare programs against the benchmark. It helps increase understanding of how the program’s scope, magnitude, cost, efficiency, efficacy, etc. compare to others.

-

Matching: Funders can match the outcomes, interventions, context, etc., they’d like to fund with programs doing that work, and be guaranteed that those outcomes will be achieved.

-

Prediction: Nonprofit leaders can predict which interventions will and will not work in different contexts, instead of relying on expensive and complex randomized control trials to tell us the possible impact.

-

Tokenization: Social impact can be turned into a digital asset that can be sold by non-profits and bought by funders.

In addition, an impact registry could be the ultimate field-leveler. Today, impact measurement is beyond the reach of most nonprofits. That’s because it’s expensive, custom, and highly labor-intensive. A registry could democratize the tools of evaluation for all nonprofits and advance equity. By using a registry, nonprofits can be more discoverable by funders seeking to fund specific outcomes and beneficiaries. That discoverability could help nonprofits of all sizes compete for funding based on their ability to deliver results, instead of their marketing materials or connections.

We’ve designed the Impact Genome Project and its companion registry to function as a centralized repository for data on all social programs and initiatives across the world. It uses standardized taxonomies to help social programs classify and store impact data, such as program strategies, outcomes, beneficiaries, context, and evidence quality.

The chart below summarizes how existing clearinghouses and data labs compare to fully developed impact registries using the MDR-OK framework. The key differentiator is data standardization. (Click to enlarge.)

The Impact Genome is just one of several new initiatives harnessing advances in meta-data, data science, AI/natural language processing, and cloud computing for the social sciences. More innovations are underway, such as impact tokenization, DAOs, recommendation technologies, investable indexes, and marketplaces. Without a functioning impact registry, however, few of these innovations will be possible.

Data is the new currency of the social sector. Indeed, a few years ago, The Economist proclaimed that the world’s most valuable resource is no longer oil, but data. Until now, stakeholders in the social sector have had access to lots of data, but no way to refine it. An impact registry refines data and allows nonprofits to extract value from all their hard work.

It’s time we solve the impact measurement problem “for good.”

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Jason Saul.