(Illustration by Melinda Beck)

(Illustration by Melinda Beck)

I first met Bill Clarke in August 2013 over breakfast on the patio of a small hotel in Washington, DC. Bill was the president and benefactor of the Osprey Foundation, a family philanthropy based outside Baltimore, Maryland. Osprey’s largest program area reflected a keen interest of Bill’s: to improve the water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) services available to the poor in Africa and Latin America. I had a background in that sector, having launched and led the WASH program at the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, where I worked from 2005 until 2013.

In the following months, I started getting to know Bill, as well as Osprey’s strategy and existing portfolio of grants. By late October, I was familiar enough with the foundation’s grantees and its goals to begin offering him some advice.

“You could spend your money differently,” I told him.

“What do you mean?” he asked.

“Well, right now you’re spending most of your money on direct service delivery—for example, getting water and sanitation services to people in need,” I told him. “That’s a good thing to do, but those NGOs you’re funding get the vast majority of their support from much larger donors, such as the US Agency for International Development (USAID) or its equivalent in the United Kingdom or the Netherlands. And those official funders spend most of their money on drilling wells and building latrines because that’s what the politicians and voters expect. The NGOs depend on that funding, of course, but it also constrains how they operate, leaving them short of resources that aren’t tied to delivering services. So what the NGOs really need is flexible funding that lets them try new approaches or reflect on what they’ve been doing.”

“What’s the catch?” Bill asked.

“Well, there are two catches. First, if you’re going to provide an organization with untied funding, you need to be very comfortable with how it’s run—strategy, implementation capacity, management, governance, the works. In the case of your existing set of grantees, I’m comfortable with some of them and less so with others. Second, you, as the funder, won’t be able to see a direct outcome from your investment. If that’s important to you, don’t take this approach. On the other hand, if you’re okay with playing an indirect role in supporting the NGO’s activities, then it makes sense. Better yet, you’d be leveraging the millions of dollars of funding from those big official donors, not to mention all the money spent by households and the countries’ governments on those basic services.”

“I like leverage,” Bill responded.

That meeting launched a host of conversations on funding strategies that Bill and I have had over the past nine years. By rethinking the roles a funder can play, we have shifted how Osprey spends its money, advises its grantees and impact investees, and uses its voice to support core program areas. In doing so, we’ve developed a set of funding techniques that enable us to have a much bigger impact than would usually be expected from a small foundation. (In this case, “small” means an annual payout of about $5-6 million, with grants typically in the $100,000-300,000 per-year range.)

LISTEN: Hear more from the author about how small foundations can apply different grantmaking strategies to achieve outsized impact on Spring Impact’s Mission to Scale podcast.

The strategic flexibility Osprey has applied to its grantmaking is rare in my experience and would not be possible without certain qualities of its benefactor. Bill assesses each situation objectively and in its own context, making few assumptions. He applies knowledge informed by his professional experience in the financial sector, but he doesn’t use that lens to filter his views. He listens carefully to our grantees, partners, and staff. He doesn’t have a charity mindset, meaning that our goal isn’t to give things away but rather to help people, households, and communities to help themselves. He is also patient, works collaboratively, and likes to partner with others who share the same goals. Finally, he understands that durable approaches to international development challenges rarely involve one player implementing a quick technological fix.

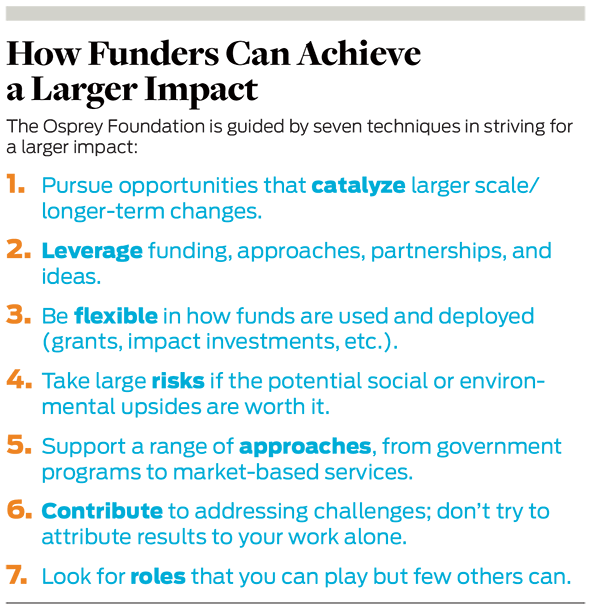

In what follows, I share seven high-impact funding techniques that smaller, and perhaps even larger, funders who seek more leverage can deploy. These techniques are broadly applicable across multiple sectors and strategies, as we’ve learned through discussions with other funders and funding recipients. Each of the techniques will be introduced by a conversation between Bill and me, starting with the exchange recounted above. (The conversations are not word for word, but they give the gist of discussions we had.)

1. Flexible Funding for Aligned Practitioners

Picking up on my conversation with Bill about providing untied support instead of directed funding, I have learned just how useful $250,000 in flexible funding can be for an organization with a $15 million budget. But this tactic makes sense only if the organization is strategically aligned with the funder’s perspective on how to achieve success in a given area. For example, in the WASH sector, Osprey holds the view that success—which we define as getting everyone in a community affordable and truly sustainable WASH services—requires a combination of systems change and collective action.

In addition to alignment on the substance of their strategies, our grantees in this category share two other attributes. First, they fully appreciate the strategic context in which they operate. This means that they understand both the broader system in which they’re working and their specific role in that system. In foundation parlance, these organizations can articulate the difference between an overall “theory of change” for their sector and a specific “theory of action” for their organization. A surprising number of organizations, both NGOs and social ventures, can’t draw this distinction, and that can lead to muddled strategies. Second, these grantees are also purposefully, and proudly, learning organizations. They have the desire, capacity, and dedicated budget to learn from their own experience and that of their peers, and to share their learning with others. They also have the intention and ability to adjust their course based on that learning.

These are the types of organizations that make strong candidates for flexible funding (assuming they too meet the usual criteria concerning governance, leadership, management, execution, and so on). A few of Osprey’s existing grantees fell into this camp, and we’ve added some new ones too. As a result, we’ve ended up with a handful of well-aligned grantees that receive flexible funding for two to three years, with a good likelihood of renewal. Besides shifting these grantees from tied to untied support, we’ve engaged more actively with their management teams and in one case have even taken a seat on its board.

2. Internal Advocacy for Aligning Practitioners

Osprey had other WASH grantees too, some of which were not, from my perspective, following good practices and seemed unlikely to change. (We phased these out over time.) But then there was a third, in-between group, which called for a different approach and occasioned a number of discussions with Bill, such as the following.

“What about our water and sanitation grantees that aren’t fully aligned with our preferred approach?” Bill asked me. “How do we handle them?”

“Fair question,” I responded. “Take CARE, which operates in a few dozen countries. In some of those places, CARE is taking the right approach—in fact, it’s widely recognized for pursuing best practices in systems change and collective action. But in other countries, they’re taking a more conventional route, perhaps because a funder just wants to count the number of wells drilled, regardless of whether they’re likely to last a long time. The good news is that CARE’s global team knows the difference between these approaches and has recently updated their strategy so that it focuses on systems change.”

“So, how should we work with them?” Bill asked. “I remember a few years ago CARE used some of our money to produce a lessons-learned report, which helped spread the word on good practices from the stronger country programs to the weaker ones.”

“I propose that we double down on that type of internal advocacy and support,” I replied. “For example, CARE’s global water leadership team wants to benchmark all country programs against principles of good practice, and they want to continue documenting what works and what doesn’t. If we fund the global team for that type of work, we’ll be influencing all of their country programs—which collectively spend $30 or $40 million each year on water and sanitation—to align more closely with effective ways of working. We may also influence other program areas, such as food security and nutrition.”

The logic of this approach is grounded in the structure of the large, international NGOs that we wanted to influence. These organizations have decentralized much of their decision-making and staffing to the country level. This structure has many benefits, most notably that it empowers those closest to the people being served. But it can also lead to a high degree of variability in how programs are implemented, which can be challenging in sectors, such as WASH, where the most effective approaches (systems change, collective action) are not the most instinctive (drill wells, build toilets). As a small funder, we can never hope to fund enough country programs. What we can do, however, is to support the small global WASH teams of these large NGOs—internal advocacy, technical advisory, and learning units—if they are helping their country programs to adopt better practices.

Although the funding provided in this approach goes to specific units, the money gives the recipient organization flexibility. These internal teams almost never get direct funding but rather rely on allocations from a central pool of (coveted and limited) untied money. So, by directing money this way, the funder is influencing activities at the country level while also signaling to the NGO’s top management that someone outside the organization recognizes and values the work of that central unit. Such a message can be reinforced through periodic meetings between the funder and the NGO’s leadership, adding the funder’s voice to its money.

Osprey was fortunate enough to experience the best-case scenario of this funding technique recently. We were providing $100,000 per year to the internal advocacy and technical support unit in WaterAid, which has an annual budget of more than $100 million. When WaterAid undertook a yearlong, in-depth review to craft a new long-term strategy, that internal unit had the resources and capacity to provide input and leadership. I can’t say for certain that the resulting strategy would not have emphasized systems change and collective action to the same extent if we hadn’t been funding the internal unit, but Bill and I were pleased that we didn’t have to find out.

We’ve also had less fortunate experiences, where we engaged with grantees that claimed they wanted to make a strategic shift but ultimately failed to follow through. This risk is one of the drawbacks of being open about your strategy: It can make playing upon your interests easier for grant applicants. We’re mindful of this possibility, of course, so we work diligently to gauge potential grantees’ actual intentions. We do this through direct discussions and by speaking to other practitioners and funders to benefit from their experience in dealing with an organization. But sometimes we misjudge an organization, in which case we end the relationship after the first grant and then reflect on what we learned.

3. Backing a Coordination Hub

In September 2018, we were considering a substantial increase in our funding to a global hub for WASH organizations dedicated to strengthening local systems through collective action: WASH Agenda for Change. The hub had been launched several years earlier and had developed to the point where the members wanted to hire full-time staffers for the first time.

“There are two ways to look at this opportunity,” I told Bill. “From one perspective, this is as a great way to achieve leverage: Our grant would position the small hub team to improve member organizations’ effectiveness in dozens of countries. In turn, those country programs would influence decisions made by households, communities, and governments about how to achieve safer and more sustainable water, sanitation, and hygiene services. So our grant of $400,000 per year could help to shape the way hundreds of millions of dollars are spent at local and national levels.”

“And the alternative view?” Bill asked.

“Some would say that we’re idiots to pour money into an initiative that’s so far removed from the households and communities we want to help,” I said. “Spending our funds in such an indirect way increases the risk that something will go wrong somewhere between the entity we’re funding and the people we want to serve.”

Very few funders will even consider supporting a coordination hub, given its indirect path to impact. This mindset gave Osprey all the more reason to consider it.

“Let’s discuss this further,” Bill said.

Why is it worthwhile to fund a hub that doesn’t deliver basic services to the poor but instead facilitates learning, coordinates practitioners, and advocates for a particular approach to delivering those services? The answer to that question is threefold. First, the approach that the hub supports—using collective action to achieve long-term systems change—is essential to success in the WASH sector. Systems change is the primary focal area for Osprey’s sector strategy, so we had strong strategic alignment with the hub. Second, experience with these types of collective-action approaches has demonstrated that having a hub is an essential element of success.1 For this reason, when we heard in May 2015 that four leading WASH organizations had proposed a set of principles for collaborative approaches in the sector, we jumped in to help move it forward. A year later, we provided some initial funding while continuing to participate in the hub’s steering committee. Third, very few funders will even consider supporting a hub, given its indirect path to impact. This mindset gave a funder like Osprey all the more reason to consider it.

That said, we did not make the decision to fund the hub lightly. We saw a range of challenges to overcome to realize the hub’s promise, the largest of which was getting organizations to work together when they would otherwise have “competed” for funding from the same sources. We have engaged actively in the governance of the hub, both to provide an independent voice among the practitioners and to learn from the hub’s experience. We have supported its evolution through several phases of growth, including at one point commissioning an external evaluation of the hub’s internal functioning and relations with its members. Other foundations have joined us in funding the hub’s work. Most of them, however, prefer to fund work at the country level, so we remain the principal supporter of the three-person international coordinating team.

Seven years into our relationship with the hub, it is realizing its promise, following a restructuring completed in 2021. That effort yielded an updated strategy focused on supporting country-level collaborations, a new governance structure led by the country collaborations, and new leadership, based primarily in Africa. Our commitment and patience appear to be paying off, and we’re achieving the leverage that we hoped this investment would generate.

4. Common Goods for Social Innovators

In our efforts to reach the poor with more sustainable and affordable basic services, Osprey doesn’t just support NGOs working to strengthen systems. We also invest in social enterprises that devise and test new ways of delivering those services. These impact investments are part of our program area funding innovative models. This part of our portfolio has led to many discussions with Bill, one of which did not follow our usual pattern of diving into the particulars of an individual venture.

“Bill, I’ve got an idea for how to make the most exciting part of our work more boring, but perhaps also more effective.”

“What do you mean?” Bill asked.

“Our innovation portfolio is made up largely of early-stage social ventures,” I said. “We’ve chosen each of these impact investments for its potential to demonstrate new and better ways to deliver basic services to the poor. Other impact investors we know have similar portfolios funding social ventures, often in the same fields where we’re investing.”

“But what if this fascination with individual ventures means we’re all missing an opportunity to identify and study challenges common to the social entrepreneurs in a given field?” I asked. “Could such a study help accelerate the progress of multiple ventures in developing viable business models?”

Bill replied, “Why don’t you see what other impact investors think about this idea?”

Osprey has chosen to focus its international-development efforts in two main program areas: WASH and cleaner cooking. The decision to concentrate on only two sectors makes sense, given our comparatively limited funding and staffing and our belief that if we’re sufficiently well informed about those sectors, we can craft and execute strategies that will make a difference in people’s lives. We’re also comfortable making both grants and impact investments.

In practice, our choices of impact investments have been even more narrowly focused. We’ve selected a few subsectors in each program area—for example, safe water enterprises and container-based sanitation—that we believe have high potential to serve the poor with better, more sustainable, and more scalable approaches. Further, within these subsectors we look for market leaders—those ventures with the capacity to demonstrate and scale up new business models and to track and share their learning along the way.

Still, supporting individual social ventures has its limitations, no matter how well chosen they are. I learned that lesson a decade ago when I contributed to a study on how to scale up innovative market-based solutions that serve the poor. Bearing that learning in mind, in 2016 I thought it might be worthwhile to support an in-depth study on one of the subsectors where Osprey had impact investments: safe water enterprises. (SWEs are ventures that use kiosks, small piped systems, or other decentralized approaches to deliver affordable, safely treated drinking water to underserved cities, towns, and villages.)

It turned out that another SWE funder was already thinking along the same lines, and in the end five of us—three private foundations, one corporate affiliate, and one government-backed funder—decided to cofund an analysis of SWEs. Of note, the SWEs themselves were initially less keen on the study than the funders, perhaps because the ventures believed they already understood their businesses fully or feared losing proprietary knowledge and practices. With some encouragement from the funders and assurances from the consultant, Dalberg Global Development Advisors, 14 SWEs agreed to participate in the study on an anonymized basis. Each participating SWE received a customized report solely for its use, and the broader study (with anonymous data) was shared publicly in 2017.

From Osprey’s perspective, the insights in this report on the fundamental challenges facing SWEs—such as customer engagement and operating efficiency—were well worth our share of the consultant’s costs. The study has given SWEs a deeper understanding of their business models and operating environments. Its lessons have also guided Osprey’s relationships with individual SWEs and our broader strategy for engaging with the subsector. Furthermore, four years after the original study, Dalberg conducted a second study, this time to assess the impact of climate change on SWEs, with support from four of the five original funders, including Osprey, and one other funder. The findings from that study have helped SWEs plan for the long-term implications of climate change.

The 2017 report also helped encourage the SWEs to talk among themselves about common challenges. These discussions contributed to the establishment in late 2018 of the SWE Community of Practice (COP), a coalition of nine SWEs that believe the benefits of working together on several shared priorities outweigh the costs of participation. Small social ventures often see the costs of such collaboration as quite high because of their very limited capacity for any activities beyond their immediate business. The COP members alone set its priorities, which currently include increasing their knowledge of their social impact and their consumers, developing a common financial framework, and advocating on behalf of SWEs.

Osprey has provided funding for the COP’s activities because it expects the value of deeper understanding in these areas to far exceed the COP’s costs. This is a relatively new effort—and one that suffered noticeably during the pandemic as the SWEs hunkered down and focused on their own survival—but we believe it will generate important learning that multiple SWEs can apply to improve their impact, sustainability, and scalability.

5. High-Risk Impact Investments

In November 2019, Bill and I attended a conference in Nairobi, Kenya, organized by the Clean Cooking Alliance, the global industry association dedicated to making the simple act of cooking a meal healthier, more economical, and better for the planet. During a break between sessions, Bill told me about a contact he had made.

We were intrigued by the potential to play a role that suits Osprey particularly well: entering into risky, pioneering transactions that set a catalytic example for others to follow.

“Our friends at BURN Manufacturing would like to meet with us tomorrow morning,” he said. “They want to discuss whether we could make a loan to expand the sale of their charcoal cookstoves in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Better yet, the loan would be repaid by the proceeds from selling carbon credits in Korea.”

“That sounds interesting,” I replied. “And I’ve had a request for a meeting with a Dutch group, Cardano Development, that first reached out to me over a year ago. They want to pitch a transaction involving outcome payments for health and gender benefits. It’s analogous to paying for carbon credits, except that in this case someone would pay for quantifiable health impacts and benefits to women. Those benefits would come from using clean cookstoves here in Kenya or in other countries in East Africa.”

“Let’s find out more about that one too,” Bill said.

Bill and I agreed to participate in both of these meetings because we were intrigued by the potential to play a role that suits Osprey particularly well: entering into risky, pioneering transactions that set a catalytic example for others to follow on a larger scale. These demonstration transactions need to align well with one of our program areas and to generate clear social and/or environmental benefits—criteria that both of these opportunities met. Furthermore, we don’t want to pursue one-off deals that look flashy but in practice have little chance of replication at scale. In both of these cases, we knew that other funders with much deeper pockets than Osprey’s, including larger impact investors and official development agencies, were interested in these types of transactions. But those larger players typically don’t have the risk appetite, flexibility, or patience to develop new funding structures. This is where smaller players like Osprey come in. Yet even for Osprey, playing the role of the pioneer can stretch our patience and pockets, as we learned when we followed up on those two initial meetings in Nairobi.

The second meeting led to a transaction that offers one of the few examples of results-based payments for health and gender benefits. The use of clean cookstoves generates multiple benefits over basic cookstoves or three-stone fires: fewer respiratory infections, due to reduced indoor air pollution; time saving for women, because the stoves require less wood, cook faster, and keep pots cleaner; reduced deforestation; and lower greenhouse gas emissions. However, while these benefits are potentially accruing when improved cookstoves are in use, they are rarely being measured or valued—which means that nobody is likely to pay for them. The main exception to date has been carbon credits, for which a growing corporate and retail market exists. The concept of paying for health and gender benefits is appealing both socially (these are two of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals) and economically (these are positive externalities that merit public support). But in practice, figuring out how to value, quantify, measure, and verify these impacts has been a daunting proposition, so the concept has yet to become a reality.

We found the combination of big upside potential for social good and a risky first step to show how it can be realized in practice quite appealing. Further, we were being asked to play a critical role in the proposed transaction, which would be structured in the following way: 1) A clean-cookstoves company would take out a loan, the proceeds of which would allow the company to reduce the retail price of its stoves and expand sales to poorer customers. 2) As the stoves were used over several years, they would generate health and gender benefits (in this case, illnesses avoided and hours of women’s time saved). 3) If those benefits were verified independently, an outcome payer would purchase the benefits at a predetermined price. 4) Those payments would be used to repay the initial loan and cover transaction costs, and any residual would go to the cookstoves company.

Within this structure, Osprey was asked to be the outcome payer because the transaction manager, Cardano, had already approached more than 100 other potential funders, without success. Outcome payers are usually official development agencies, such as USAID, that like this role because they disburse taxpayers’ funds only when development objectives are met. While some official development agencies showed interest in the concept, the risks of an untried structure were too great for them to handle—but not for us.

As clear as this structure seemed in principle, pioneering transactions always present unanticipated challenges. What’s the right metric for gender benefits? How do you price those benefits? How do you implement field studies to measure health and gender benefits? How does the impact verification process work, and who will oversee it? Cardano has shouldered most of the financial burden for addressing these and other challenges. But when the cost of the preparatory activities exceeded the expected level (most of which was generously funded by the International Finance Corporation of The World Bank Group), we made a supplemental grant to reduce the cost burden on Cardano. The transaction was finally executed in September 2022 after the potential health and safety benefits were determined to be quite substantial. The parties to the transaction plan to share the model widely to promote replication at much larger scale, and with much shorter project development times and lower transaction costs, now that we’ve begun to pave the way.

The first meeting at the conference in Nairobi also resulted in a useful transaction, a loan from Osprey to BURN Manufacturing to support expanded sales of cookstoves to poorer customers in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. This loan would be repaid solely from the proceeds of the sales of carbon credits generated by the use of those stoves. However, the most interesting aspect of the loan initially—the possibility of selling carbon credits into the Korean market, which pays a much higher price than other markets—did not materialize. As a result, we ended up with a transaction structure similar to that used by lenders specializing in the carbon market. With limited background in this area, we engaged a financial advisor specializing in the carbon markets and a legal advisor with deep international experience. These experts informed Osprey’s positions and protected our interests while also ensuring that the structure and documentation of the transaction would meet the highest standards, making it easier for other nonspecialized impact investors to follow our lead in the future. We also wrote a briefing note detailing the rationale, structure, and terms of the transaction, again with the goal of encouraging other impact investors to pursue similar opportunities on a larger scale.

6. Proactive Engagement With Other Funders

It was March 2019, and Bill and I were leaving a meeting in The Hague with about a dozen other WASH funders. Osprey had helped to organize the meeting, along with five other funders with whom we had been loosely collaborating for the previous four years. Other WASH funders had heard of our informal group, so, the day before a major conference, we invited a number of them to meet with us.

“Bill, do you remember that idea you had in early 2015 about engaging other funders in the WASH sector?” I asked. “You wanted to see if they would be interested in cofunding expert advice on how to have a deeper impact in the sector.”

“Is that the one where we had a short study done on how it might work in practice?” Bill asked.

“Yes, that’s it,” I said. “We put the work on hold when it became apparent from interviews with other funders that they weren’t inclined to collaborate in that way.”

“Why do you ask?”

“Well, I was thinking about that study today because I believe we’re starting to realize your vision,” I said. “I know it’s taken a while, and we’re not going to arrange cofunding of strategic advice, but I think we’re finding effective ways to learn from our peers and to influence how they work.”

I came to think of my cofunders as colleagues on whom I could rely as if we belonged to the same organization. I also got to learn from thoughtful partners who asked tough questions.

One of the things about being a small funder with big ambitions is that you think a lot about leverage. Osprey employs several different types of leverage: financial (catalyzing other sources of funding to increase the money flowing to a targeted activity), demonstrative (setting a replicable example for others to follow on a larger scale), relational (learning from like-minded organizations while also influencing how they work), and conceptual (generating new ways of thinking about what constitutes success, as well as the paths to get there). I had used all of these approaches to varying degrees in previous positions, but I had far less experience pursuing them on my own or with only a few colleagues. I came to Osprey from large institutions where I could rely on internal teams, drawn both from my own unit and from other departments. And before I joined Osprey, Bill had done most of the grantmaking himself, with some assistance from a philanthropic advisory firm and his family. (Several years after I joined, we decided to hire a half-time program officer, Lauren Maher Patrick, to work with me and manage part of our WASH portfolio.) I came to understand that working in a small shop has both upsides (flexibility, quick decision-making, and rapid course corrections) and limitations (staff time is usually our constraining factor). In response, I started to build up a cohort of colleagues from other small foundations, who helped to enhance our impact, sharpen our thinking, and provide an unexpected source of camaraderie and friendship.

I would like to take credit for organizing the first meeting of WASH funders in November 2015 in London, but I can’t. That honor goes to The Stone Family Foundation of the United Kingdom, and indeed it was meant to be for British funders, until I asked to join and suggested that we invite another US group, the Conrad N. Hilton Foundation. Starting from that initial meeting, the six of us (four UK foundations—The Stone Family Foundation, Vitol Foundation, The Waterloo Foundation, and The One Foundation—and the two US foundations) met periodically over the next three and a half years to share our strategies, exchange notes on current or potential grantees/investees, and learn from each other’s experience. It was an informal group, and we met around sector conferences or when other travel brought us together.

The most formal arrangement we made was contributing to a spreadsheet, which The Stone Family Foundation kindly managed, with the current WASH portfolios and planned pipelines of grants and impact investments for all six foundations. That helped us to get a clearer picture of which organizations we were cofunding and how our strategies were being put into practice. We also used the forum to arrange cofunding of studies (such as the SWE report described above) and occasionally to ask for favors (such as when Vitol shared its field report on a potential grantee in a remote part of Ghana, which Osprey then decided to fund). In those cases, I came to think of my cofunders as colleagues on whom I could rely as if we belonged to the same organization. I also got to learn from thoughtful, strategically driven partners who asked tough questions and offered insightful perspectives, some of which aligned with ours and some of which didn’t.

Given this initial success, we invited a number of other WASH funders to meet with us in The Hague in order to gauge interest in expanding our group. That meeting went well, so we pursued the concept further. The engagement resulted in the launch of an expanded and somewhat formalized WASH funders group in June 2020 that included 18 members—the 6 original members plus 12 others. Since that date, under the guidance of a part-time coordinator based in London, we have held multiple virtual meetings on topics ranging from what systems change means in the WASH sector to menstrual hygiene management to climate change. The coordinator has also overseen the development of an online database with information on all of our existing and potential grants and investments, with analytics on cofunding and strategic alignments. As of June 2022, the group has grown to 26 members, most of whom are actively participating in the meetings to share strategies and the learning sessions. On the basis of these meetings, one funder even convinced their board to make a strategic shift toward funding systems change. This is just one of the signs indicating that we are expanding our influence with and learning from other WASH funders.

7. Changing the Debate

The trip that Bill and I, along with Lauren, took to The Hague in March 2019 was quite productive. After we met with the WASH funders, we attended the three-day All Systems Go symposium. That conference focused on systems change in the WASH sector and was hosted by IRC WASH (IRC), one of Osprey’s systems-change grantees and a founding member of the WASH Agenda for Change hub.

As we headed back to our hotel after the closing session, I asked Bill, “What did you think of the conference?”

“They did a great job,” he replied. “The themes and session topics and speakers reflected a lot of thought and preparation. My only complaint was that I often wanted to attend more than one session at the same time.”

“I agree,” I said. “But that’s a nice problem to have. Many of the sessions I attended moved the field forward—which is my highest compliment for a conference. I think much of that success is due to how IRC organized it: They worked with 12 other WASH NGOs as cosponsors to choose the conference themes and design the sessions.”

“Well, that approach clearly paid off,” Bill said.

That conversation reminded me of another exchange I’d had 30 years earlier, when one of my mentors, Shinji Asanuma, left a senior position with an investment bank in Tokyo to return to The World Bank. Shinji had started his career several decades earlier at The World Bank, and he was rejoining as a senior manager. I asked Shinji what he was planning to do from that new perch. “Louis, some people manage projects,” he said. “Others manage people. I want to manage ideas.” That was my introduction to conceptual leverage, the use of new or improved ways of thinking about a major challenge in order to alter fundamentally how it is addressed.

Many years later, I had the opportunity to see this approach tested at scale. A colleague of mine at the Gates Foundation, Rachel Cardone, developed two large grants with IRC (note that I later joined the board of IRC, well after I had left the Gates Foundation). One of the grants demonstrated the concept of sustainable service delivery: Instead of seeking simply to drill more wells or dig more latrines, this grant defined success as ensuring that households and communities had sustainable WASH services. This wasn’t the only initiative to focus on that new definition of success for the WASH sector, but it was highly influential because of IRC’s strategy to encourage other players—from governments to international donors to UN agencies—to adopt the approach.

The second IRC grant developed and tested the concept of all-inclusive, life-cycle costing for WASH services, which involves accounting for up-front capital costs, ongoing operating costs, periodic capital improvement costs, and the costs to regulate the sector. This method contrasted sharply with the conventional approach of considering only capital construction costs. Again, IRC promoted this way of thinking throughout the sector.

Both of these initiatives helped to change the debate in the WASH sector by redefining what success looks like (sustainable services) and what it takes to attain that success (comprehensive costing). Admittedly, it’s easier to support this type of effort with the resources and name recognition of the Gates Foundation. But smaller funders still have opportunities to apply conceptual leverage to change the thinking and practices of a sector. For example, Osprey has relentlessly advocated for systems change as the way to achieve sustainable WASH services. We have also been an avid funder and vocal promoter of the Uptime initiative, which we believe is fundamentally changing the debate on rural water services. Uptime has developed and implemented a results-based approach under which rural water service providers are paid a supplemental fee only if they meet agreed-upon performance criteria, such as having water available at least 29 days each month. Supporting such innovations can have far-reaching impacts that improve the way basic services are delivered and funded.

Maximizing Catalytic Effects

Osprey has come a long way since Bill and I had that first breakfast meeting more than nine years ago. The guiding principles and values that motivated the Clarke family’s decision to establish the foundation have not changed, but the strategies and approaches we use to realize that vision have shifted in order for us to maximize the catalytic effect of our funding and our people.

We expect to continue using the techniques described here; to find new ones; and to keep learning from our funding recipients, fellow funders, and other partners. The better we get at doing that, the more effective we’ll be at supporting the delivery of basic services to those most in need.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Louis C. Boorstin.