Neither those who knew the debonair young Fazle Abed nor Abed himself would have imagined how the course of his life would change forever with the deadly cyclone that hit Bangladesh in 1970. Killing as many as 500,000, the event was profound in its impact, devastating the lives of more than 3 million people, leading ultimately to the bloody liberation of Bangladesh, and launching one Shell Oil executive on an entirely new career path.

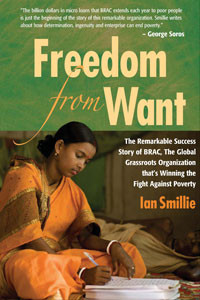

In Freedom from Want, Ian Smillie chronicles the life and times of the newly formed nation of Bangladesh, its largely impoverished people, and an organization that would come to master both the art and science of development. Told as a laudatory case history, the book proceeds predictably. Smillie begins by tracing Abed’s privileged upbringing and early career, digressing to document the Abed family’s Bengali roots and the British imperialism that would lead ultimately to independence for Bangladesh, but quickly establishes a narrative pattern: Issue by issue, we learn how brac experiments with education, health care, and income generation; figures out how to integrate and scale up effective programs and enterprises; and drives to ensure lasting benefit to those served.

This is a well-told account of an unlikely NGO leader who learns early on that development is a humbling business. Abed and his colleagues, many of them extraordinary individuals themselves, graduate quickly from their early experiences with relief—distributing blankets, food, water, and medical supplies to those suffering in the cyclone’s aftermath—to take on the challenge of a society defined by endemic poverty, with its underlying conditions of illiteracy, the oppression of women, and hand-to-mouth livelihoods.

That the organization’s first giddy forays at development fall short of expectations is not all that surprising. What sets BRAC apart, however, is an unflinching willingness to acknowledge failure. Early attempts to reform education and shape new fishing and farming cooperatives considered “not too difficult to achieve,” for example, fall flat, with brac reporting “disappointing results” and sobering lessons back to its funder, Oxfam, a practice as remarkable then as it would be today. For Smillie and others, brac is a learning organization, committed to investing whatever it takes and as long as it takes to figure out what works. Failures are grist to the mill of better ideas, and that mill a laboratory for systemic solutions.

Smillie’s account of brac’s entry into microfinance, the field identified with Muhammad Yunus, founder of Bangladesh’s Grameen Bank and winner of the 2006 Nobel Peace Prize, sounds one of the book’s only sour notes. After establishing the roots of microlending in 18th-century Irish Loan Funds, Smillie ultimately characterizes as “fantasy” current popularization of this “idea of a miracle cure that will emerge fully formed from the womb, end poverty, and be completely sustainable from the outset.” He juxtaposes a microfinance paradigm that begins and ends with the “loan as the point of departure, on the assumption that development will follow” with brac’s more enlightened view of the development enterprise as first and foremost. For Smillie, Yunus’ dictum that the “borrower knows best” and the Grameen model wind up reinforcing “subsistence activity,” whereas BRAC’s superior method advances scalable enterprise. As an admirer of both Abed and Yunus, brac and Grameen, I found this invidious comparison off -putting, even demeaning to the towering achievements of both men and their organizations.

But this is a minor cavil. Smillie’s account of Abed’s journey and brac’s stunning record over nearly four decades evokes Amartya Sen’s characterization of “development as freedom.” brac has proven through its holistic approach that poverty can be defeated, lives transformed, and prosperity sustained. Moreover, the organization has insisted that the innovations necessary to drive such change achieve scale. “Small is beautiful,” says Abed, “but big is necessary.” Today, brac generates 80 percent of its nearly $500 million annual budget, exceeds $1 billion in its microfinance lending, and operates in multiple countries, including Afghanistan, Pakistan, and the Sudan. Freedom from Want pays well-deserved tribute to an exemplar of indigenous development and its magnificent leader.

Sally Osberg is the president and CEO of the Skoll Foundation. Before joining Skoll, Osberg was executive director of the Children’s Discovery Museum of San Jose.