This series of articles has aimed to spark conversation around whether and how the social sector can make a difference in improving US voter turnout. Thirteen experts, and many commenters, have shared their views—and we’ve also had the benefit of studying the current primary election cycle. What have we learned?

After a long decline in US voter turnout, the turnout rate for the current primaries has rebounded to almost 30 percent—the second highest level since 1980, and only one percentage point off from the 2008 Obama high. A variety of structural factors discussed in this series have been in play, both good (e.g., improved registration) and bad (remember the long lines in Arizona?).

But perhaps as important are factors well outside of reformists’ control. The level of competition in particular campaigns and the enthusiasm (or abhorrence) inspired by various candidates matters a lot. We have seen plenty of both in the nominating contests so far this year.

While these factors are harder for the social sector to influence, other levers remain—though the likely impact of most traditional voting interventions may not be high. For me, three themes stand out:

- There is no silver bullet for increasing turnout—a mix of strategies would need to be pursued, each (on their own) with incremental effects.

- Improving the representativeness of the electorate, and knowledge about policies at stake, may be a more important (and realistic) goal than dramatically increasing overall turnout.

- Primary elections routinely see lower and even less representative turnout than general elections—and therefore may offer a particularly good opportunity for philanthropy to make a difference.

No Silver Bullet

A range of structural changes could each bring about relatively modest percentage point increases, mostly in the single digits. Wendy Weiser of the Brennan Center advocates making voter registration easier, noting that “making registration portable can boost turnout by more than 2 [percentage points],” while “allowing citizens to register at their polling place on election-day increases turnout [by] typically 5 to 7 [percentage points].” Though harder to achieve, transitioning to a multi-party system with an electoral process that allocates representatives proportionally—the system in Nordic countries and others with high voter turnout rates—could encourage greater engagement in the political process, writes George Cheung of the Joyce Foundation. This could boost voter turnout between 9 and 12 percentage points—also not a huge increase, and very difficult to bring about.

Others are more skeptical. Citing half a dozen scholars’ research on efforts to reduce barriers to voting (by allowing early voting and relaxing stringent absentee balloting procedures, for example), MIT’s Adam Berinsky concludes, “The balance of evidence is clear: lowering the direct costs of voting does little if anything to increase turnout.” Similarly, David Becker of the Pew Elections Project notes that “it’s never been easier for the majority of US voters to get election information and cast their ballots… [but] turnout declined last year to levels not seen since World War II.”

Other contributors argue mobilization efforts that don’t require structural or legal changes. Kate Lydon of IDEO argues that we need a more nuanced understanding of why different groups are motivated (or not) to vote, and suggests that—depending on the audience—voter mobilization efforts should highlight one of three key factors influencing voting behavior: impact, convenience, or community. Contributors such as former Minnesota Secretary of State Mark Ritchie attribute much of the variation in turnout across counties to differences in community culture and values. Becker likewise emphasizes the need to examine differences between subgroups, arguing that we need a more nuanced segmentation of voters to understand the myriad barriers and disincentives that different groups face.

But Alan Gerber and Greg Huber of Yale University caution against expecting traditional get-out-the-vote (GOTV) efforts to have a significant impact on turnout. “The key messages are that (1) it is quite challenging to increase turnout and (2) commonly used interventions produce effects on turnout in the low single digits,” they write. And it’s worth noting that any civic education or mobilization efforts require repetition (and funding) year in and year out—meaning less of an enduring impact than structural reforms could have.

Representativeness

Improving the electorate’s representativeness and understanding of policy issues may be a more important target than trying to radically increase turnout.

As noted at the series outset, philanthropy remains a drop in the bucket compared with what parties, candidates, and interest groups spend on mobilization efforts. Moreover, with the federal prohibition on electioneering by 501(c)3 organizations, there are many things nonpartisan philanthropies hoping to increase civic engagement—regardless of the election outcome—legally cannot do. Yet several contributors make a convincing case that the social sector can play an important role in areas where others are not incentivized to act. Parties and interest groups invariably focus on voters they think are going to turn out (and turn out for them). This leaves a lot of ground uncovered. Philanthropy could make a distinctive impact by helping better inform both voters and nonvoters about policy issues, helping improve the representativeness of the electorate, or increasing turnout in America’s ill-attended but increasingly important primary elections, as several contributors discussed.

The population that turns out to vote often differs notably from the US population at large.

- The gap between white and black voting rates has narrowed since the 2008 elections in both presidential elections and midterms, but white Americans’ turnout rate is still almost 20 percentage points higher than Asian or Hispanic turnout in both types of elections.

- Voters age 65 and older still turn out at a rate almost 30 percentage points higher than 18- to 24-year-olds.

- The turnout rate among those earning more than $100,000 to $150,000 per year remains 30 to 50 percentage points higher than the rate for those earning less than $20,000.

So, what can be done to improve the representativeness of the electorate? Professors Jan Leighley and Jonathan Nagler suggest that the best way to increase turnout and improve the representativeness of voters (whether by age, race, or income) may be by increasing the information citizens have about candidates’ policy positions. Berinsky agrees, and notes that structural reforms “designed to make voting ‘easier’” can actually “magnify the existing socioeconomic biases in the composition of the electorate.” This skewing happens because reforms that make the act of voting easier (e.g., online voting) may help to retain people who are already engaged and inclined to vote, but do little to stimulate the unengaged, who may be more daunted by the cognitive costs of voting than the logistical ones.

Abby Kiesa and Peter Levine of Tufts University focus specifically on youth turnout, but their argument for a multi-pronged approach is as relevant for the rest of the electorate. They recommend a combination of structural reforms (same-day registration, pre-registration programs, and a voting age of 16 or 17 for local elections), civic education to influence cultural norms, and get-out-the-vote efforts.

The Importance of Primary Elections

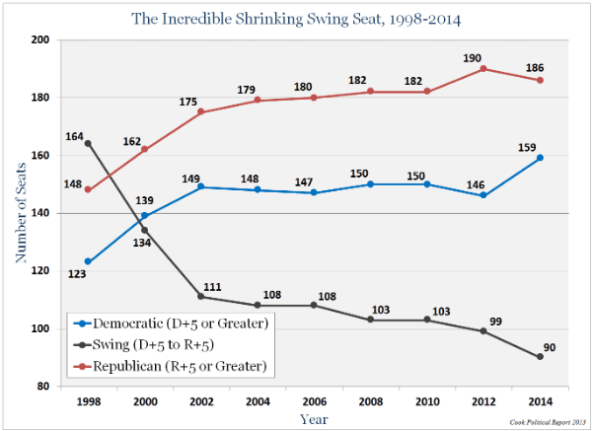

Our final contributors took on primary elections—a new and (almost) uniquely American invention. Most other democracies (and the United States, too, until the 1970s) rely on party leaders to develop candidate lists. But primaries (particularly Congressional primaries) play quite an important role in US politics, in part because most voters see them as so—well—unimportant. They shouldn’t: Around 80 percent of Congressional districts are either solidly Democratic or solidly Republican enough to be considered “safe” for that party. That means it’s the voters who participate in those districts’ primaries that really decide the election. Primaries have become the de facto general elections—and in these safe districts, the actual general elections no longer matter.

The number of seriously contested seats in Congressional elections has dropped significantly in recent years. (Excerpted from 2013 Cook Political Report, courtesy of the Brookings Institution)

The number of seriously contested seats in Congressional elections has dropped significantly in recent years. (Excerpted from 2013 Cook Political Report, courtesy of the Brookings Institution)

Parties and candidates often have little interest in addressing this disconnect between primaries’ low profile and their importance in the political process. The social sector may be able to play an important role here.

Elaine Kamarck of the Brookings Institution confirms that primary turnout remains astoundingly low: “In the hotly contested primaries of 2010 turnout averaged 7.5 percent of the voting age population.” She argues for a concerted push for all primary elections to take place on the same one or two days, rather than “spread out across 15 separate days in seven months,” as they currently are. That way, “the national press would be able to cover it as a major story,” and voters would be more likely to be engaged with the process. Parties and candidates are unlikely to pursue this recommendation on their own, leaving the social sector uniquely positioned to act. Likewise, more concerted GOTV efforts to improve primary turnout are, Seth Hill and Thad Kousser at the University of California, San Diego, suggest, something that only the social sector or government (if pressured to act) are likely to take on in a nonpartisan way. It’s worth noting, however, that although Hill and Kousser found GOTV efforts to be twice as effective in primaries as in general elections, even their impact remains small. The authors found that people who typically vote only in November, but who received a traditional GOTV mailer, voted in primaries at a rate 0.5 percentage points higher than “November-only” voters who didn’t receive the mailer. (Given that only 9.5 to 10 percent of such voters participate in primaries, this meant a 5 percent increase in turnout among this group.).

Looking at all of this, I am left with a much clearer sense of the (unfortunately, generally small) impact that most traditional voting interventions yield—but also a stronger sense of where the social sector is best positioned to intervene.

The recent GOP turnout “explosion” suggests that candidate personalities and electoral competitiveness may have a much bigger effect on turnout than many structural interventions, but these factors are also nigh impossible to control. Nonpartisan opportunities to improve turnout among specific groups, or for specific types of elections, may offer more hope. And, to end on an optimistic note, voting is sticky: 30 to 50 percent of the people who turn out due to GOTV efforts in one election will continue to vote in future elections. Moreover, although much research has been done on the impact of individual interventions on turnout, there is no way of telling what the cumulative effect of structural reforms might be—perhaps more than the sum of these parts?

In the end, whatever one’s views on whether government should be larger or smaller, an effective government remains the most viable mechanism for achieving social impact at scale, and getting Americans to vote for representatives who support their interests matters for any of the outcomes we care about.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Kelly Born.