In 2016, nearly $10 billion is likely to be spent on the US presidential election by parties, candidates, and interest groups. At the same time, many of America’s funders are also actively working to improve voter turnout and civic participation. What does the social sector hope to achieve in this already crowded field? And what can its, relatively speaking, modest contributions do to make a difference?

While social sector efforts are small compared to political parties, candidates, and interest groups, they generally have very different goals. The former are often driven by a belief that a high level of voter turnout, regardless of the voter’s political affiliation, is an important indicator of a healthy democracy, and that more engagement by voters will ultimately lead to better policy outcomes. Social sector goals commonly include increasing the number of voters, improving the quality and thoughtfulness of voting decisions made by existing voters, and enhancing the representativeness of the electorate so that it more closely mirrors the demographic profile of America. Political parties, candidates, and interest groups, on the other hand, are focused more on achieving specific electoral outcomes than on improving democracy or civic engagement writ large.

While modest by party and candidate standards, social sector investments in the voting field are far from insignificant. Foundations provide an estimated $30 million to $60 million in grants annually for voter education, registration, and turnout alone; plus another $5 million to $25 million to improve voting access (depending on whether or not it’s an election year). Add to this a few million dollars more to improve election administration, and an estimated $200 million to $300 million annually to improve “civic participation” writ large (with, no doubt, some subset focused on informing voters). Since 2011, almost 200 foundations have made about 1,300 grants totaling more than $150 million to almost 500 nonprofits to further voter education, registration, and turnout.

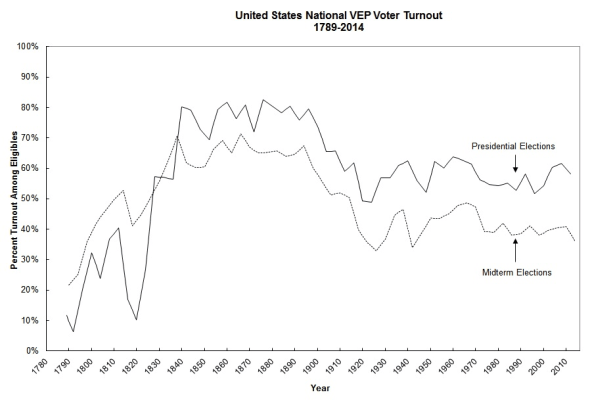

Yet despite all of these philanthropic and political investments, turnout has remained relatively stable over the last 40 years—since the cultural and structural upheavals of the post-Civil Rights era. While 2014 election turnout of 36 percent was concerning to many—the lowest in 72 years—it is unclear that it represents that significant a departure from recent years. After all, 1998 turnout was only 39 percent.

(Chart from University of Florida’s United States Elections Project)

(Chart from University of Florida’s United States Elections Project)

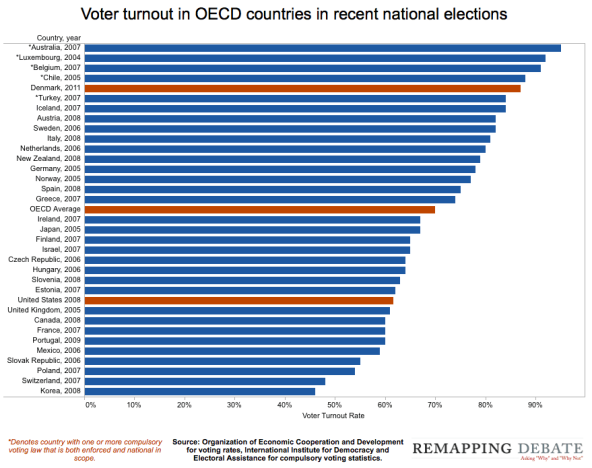

And while US turnout remains below the OECD average, it’s not that far below, especially when considering that a number of these countries have some current or prior form of mandatory or universal voting (including all of the top five except Denmark).

Given the relatively stagnant rate of US voter turnout, what can realistically be done to improve it, and how can this best be achieved?

The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation’s Madison Initiative is squarely focused on improving dialogue, negotiation, and compromise in Congress. As we’ve explored possible strategies to improve Congress, we have had many conversations with voting and civic engagement leaders across the nonprofit and philanthropic fields. These conversations have explored both the relevance of improved turnout to our work, and the range of possible mechanisms through which to improve it. While improving voter turnout has not emerged as a key driver in our strategy, these conversations have proven fascinating enough that we wanted to share them with, and engage, the broader philanthropic field.

These dialogues have often circled around the same questions: What can the social sector do to improve US voter turnout? What distinctive goals are we equipped to achieve relative to what parties and candidates are already doing? Which kinds of interventions—informational, structural, technological, or other—are most likely to improve turnout? Where are we most likely to see impact—during which elections, at which levels of government, and with which groups of citizens? Which new and interesting approaches are being tried? And how much impact can we realistically expect to have?

Over the next few months, 13 election experts from around the country—from government, academia, and the private and nonprofit sectors—will weigh in with their insights, struggles, and questions regarding the challenge of improving US voter turnout. These experts will explore the nature of the problem, the history and impact of a wide range of efforts to improve turnout, and propose ideas for how and where to best intervene.

The series will begin by looking at the main types of interventions pursued to improve turnout. Many efforts focus on lowering the “costs” of voting, primarily through structural changes in the way elections are governed and run, or by efforts to lower the informational costs to citizens. Experts from New York University’s Brennan Center, the Joyce Foundation, and MIT will all weigh in these topics.

Other initiatives focus on increasing the perceived “benefits” of voting, trying to raise people’s incentives to or interest in turning out. This includes get-out-the-vote mobilization efforts highlighting the reasons for voting—everything from emphasizing the importance of government action or inaction on salient issues, to stressing one’s sense of civic duty, or the cultural importance of showing up at the polls. Here, Minnesota’s former Secretary of State will share his perspective, alongside experts from Pew’s Election Initiative, IDEO, Americans for Prosperity, and Yale University.

The series will then explore specific recommendations on how to mobilize turnout by particular groups (such as youth and minorities), and reflections on where nonprofit efforts may be most impactful—namely, primary elections. Experts from the Brookings Institution and MTV will contribute their perspectives, alongside leading academics from New York University, Washington University Tufts University, and University of California, San Diego.

The aim of this series of articles is to deliver a breadth of insights that will advance our collective understanding of what is, and is not, likely to succeed in improving voter turnout and promoting a robust democracy. I hope it will stimulate a broad conversation about whether and how the social sector can make a difference, and the likely magnitude of impact of possible interventions. Please join the conversation and post your own thoughts over the course of the series.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Kelly Born.