Do schools know what their students will be doing in 20 years’ time? Actually, no. And don’t believe anybody who says they do. The rate of change in society and the workplace is such that all we can say for certain is the future will be very different!

This is a problem for schools everywhere. How can they equip young people for adult life if they don’t know what jobs they might be doing or how they will live? Actually, it’s even worse than that. The list of imponderables stretches out: social relationships and communication, the construction and distribution of information, political culture and governance, civic engagement, the very nature of work—all are changing in ways we can only speculate about. The old certainties, which underpin today’s school curricula, no longer hold, and we do not know what will replace them.

Since we don’t know what sort of world lies ahead, schools should perhaps concentrate on developing individuals’ capacities, and leave vocational preparation to adult and lifelong learning. which is where it belongs anyway. This goal is not well served by today’s schools; the traditional curriculum is simply too narrow, and important areas of human experience are sidelined. It’s all very well to prioritize language, maths, and science—they are important—but when areas such as the arts and citizenship are assigned minority status, important aspects of personal development are being neglected.

Developing young people’s capacities to the full is a worthwhile enterprise in its own right and does not need further justification. But it also makes sense from a forward-looking perspective. Who are best placed to thrive in uncertain and unknown futures—those versed only in the narrow skills prioritized in today’s schools, or fully rounded adults with a broad set of competencies?

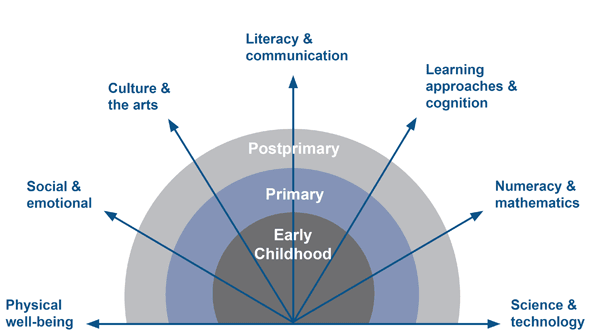

There have been numerous attempts to re-conceptualize the standard curriculum on a broader basis. One of the best-known approaches is the Seven Domains of Learning, produced by the Learning Metrics Task Force (LMTF), a multistakeholder collaboration that worked to improve learning outcomes for students worldwide, with a specific focus on strengthening assessment systems.

(Source: Toward Universal Learning: What Every Child Should Learn. Montreal, PQ/Washington, DC, UNESCO Institute for Statistics/Brookings Institution)

(Source: Toward Universal Learning: What Every Child Should Learn. Montreal, PQ/Washington, DC, UNESCO Institute for Statistics/Brookings Institution)

However, while many acknowledge the power and relevance of frameworks like these, we are a long way from widespread adoption. This is partly due to the “assessment imperative,” where schools and students everywhere focus on whatever skills and knowledge are assessed, particularly high-stakes tests that affect students’ progress through school or their access to higher education. And if, say, teamwork is not assessed, then it is marginalized in the classroom.

One way of moving forward is to document systematically what learning opportunities students have to develop the skills identified in the Seven Domains of Learning. This would entail scrutinizing national curricula and school programs in terms of their coverage of the seven domains by collecting information on time allocation, resourcing, teaching input, contribution to assessment, and certification relative to each domain. Data emerging from such an exercise would provide a factual basis for holding education systems and schools to account, and for assessing how well they facilitate young people’s full development and equip them for adult life.

This is precisely what our team at the Center for Universal Education at the Brookings Institution and Education International are attempting to do with a project called Breadth of Learning Opportunities. Our goal is to develop a set of tools to measure learning opportunities across the seven domains open to students, both in national curricula and in classrooms.

The first tool addresses the policy level. By examining curriculum statements, assessment practices, and relevant policy documents, it aims to depict systematically the intended curriculum in a policy jurisdiction (country, province, or city). For each of the seven LMTF domains, it will describe curriculum guidelines, note whether they are prescriptive or advisory, specify the time allocations given to each, and spell out their role in national assessments and examinations.

The second tool, which we have developed and pre-piloted with national teacher organizations in Kenya and Zambia, examines breadth of learning from the perspective of teachers. It focuses on teacher preparation and ongoing professional development, particularly in relation to learning domains, resources available within schools, and time spent on the different learning domains.

The third tool, still in development, focuses on students and the breadth of learning opportunities they actually experience at school level. A comprehensive national curriculum framework is worth little until schools translate it into classroom practice. The effort here will be to document the learning opportunities that students really have, and establish whether those opportunities match the intentions of national curriculum bodies and school syllabi.

Full pilots of the three tools are scheduled to take place this summer in Kenya and Mexico. When finalized, they will be openly available, along with notes on their use.

The purpose of these tools is not to draw up league tables that rank countries or prescribe how much time should be allocated to any given domain. Rather, by documenting how broad or narrow students’ learning opportunities are, they seek to provide a basis for considering whether (and to what extent) the curriculum in fact provides a broad set of learning experiences and whether there are gaps to address.

Take an area like citizenship. Some countries address citizenship as a specific subject, especially in secondary school, whereas others deem it to permeate learning across subjects. Data from the policy tool would make it possible to consider whether students have adequate opportunity, across the entire curriculum, to develop as young citizens. Data from the school tool could demonstrate the depth that the policy has taken hold, and the teacher tool would show how well equipped teachers are to impart citizenship to their students. All three tools combined could stimulate public debate about the content of school learning and contribute to curriculum revision or reform.

Our hope is that these three tools will help education systems, from policymakers to teachers, examine their curricula and achieve clarity about the breadth of learning their students have. We cannot predict what life or work opportunities that students entering school now will have in 2037 any more than we could have predicted that students entering school in 1997 would be able to work for tech companies such as Snapchat and Skype.

The future has so many possible avenues for the development of life and work. We need to start offering students the fullest possible realm of experiences and learning chances that we can, as soon as we can, so that they are as equipped as possible to navigate our rapidly changing world.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Seamus Hegarty.