The continuing disappearance of Earth’s last healthy ecosystems, on land and in the oceans, is sadly no longer news. What is news is that saving these ecosystems is affordable and even profitable. An investor-driven approach to conservation finance has the potential to preserve these vital areas, and with them the planet’s natural capital stock of clean air, fresh water and species diversity.

Conservation finance represents an undeveloped private sector investment opportunity of major proportion. Our research suggests private investors—wealthy individuals, pension funds and other institutional investors and even mainstream retail investors—could supply as much as $200 billion to $300 billion per year needed to preserve the world’s most important ecosystems, ranging from the Borneo rainforest in Malaysia and Indonesia to the African Rift lake system of Rwanda and Uganda.

If such conservation investments can be scaled up and developed into investable “conservation asset classes,” akin to more familiar investment forms such as venture capital or alternative investments such as infrastructure, there could be ample capital to finance large-scale, high-impact ecosystem conservation. We estimate approximately $300 billion to $400 billion per year is needed to meet such global conservation needs. Increases in government and philanthropic funding are likely to be modest, so the mobilization of private capital is both essential and possible.

The shift to investor-driven conservation finance requires banks, financial intermediaries, and NGOs to take on new roles and challenges. That’s why Credit Suisse, World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF), and McKinsey & Company worked together to develop a new framework, which one can read about in more detail in the recently published report, “Conservation Finance: Moving Beyond Donor Funding Toward an Investor-Driven Approach.”

From Demand to Supply

This new approach to conservation finance builds on a quarter-century of work to harness private-sector capital, through mechanisms such as carbon finance, mitigation banking, and nutrient trading. (For a good example of the public-private model. (See “A Big Deal for Conservation” in SSIR’s summer 2012 issue.)

In the past, conservation finance has largely been demand-driven, focused on trying to meet conservation needs of priority areas. Now, a shift from the demand for capital for conservation needs to the supply of capital driven by investors has the potential to move from small, segregated, niche projects to large-scale conservation markets.

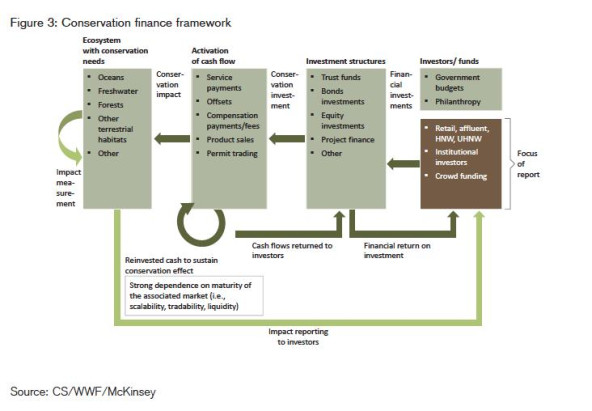

We understand “conservation finance” to be the set of mechanisms for investing in an ecosystem, directly or through intermediaries, that aims to conserve the values of the ecosystem for the long-term. That requires projects that produce actual, long-term cash flows to support both the conservation strategy and a return to investors.

Today, only about $52 billion per year flows to conservation projects, the bulk of it in public funds. According to a 2012 estimate from the Global Canopy Programme, market-based activity generates only 20 percent of the total, or approximately $10.4 billion. Of that, about $6.6 billion comes from green commodities, such as sustainable timber or fisheries, or services such as ecotourism. Another $3.8 billion comes from direct market payments, such as carbon offsets or biodiversity and ecosystem fees.

Source: CS/WWF/McKinsey

Source: CS/WWF/McKinsey

To meet the global need for conservation financing with market-based mechanisms, we estimate that investable cash flows from conservation projects need to be at least 20 to 30 times greater than they are today, There is certainly no shortage of funding capacity from the private sector. Even if only 1 percent of the new and reinvested capital of institutional investors, high and ultra-high net worth (HNW/UHNW) individuals, and retail investors were dedicated to conservation, private-sector investment could provide at least $200 billion to $300 billion required for closing the conservation funding gap per year.

Conservation finance lags a decade or more behind social impact investments in the development of asset classes and investment styles. We believe that with a focused effort, it can become similarly viable and attractive. In particular, many HNW/UHNW individuals would welcome investment opportunities that lie between philanthropic donations and return-oriented investments: wealth-preserving investments with a social or environmental impact.

Capturing conservation cash flows

Both individual and institutional investors have an appetite for conservation finance. The main constraint in satisfying this appetite is the underdevelopment of investable projects with clear risk-return profiles and understandable conservation benefits.

There remain significant obstacles to the development of investable conservation business opportunities. First, natural lands such as forests or marine areas are rarely valued for the full set of environmental benefits they provide, but rather for the goods that can be sold the most efficiently, such as timber or fish. Those who manage natural areas are generally not paid for the public goods they provide, such as clean air and water. Second, there is often a significant opportunity cost to foregoing the exploitation of natural resources, providing short-term incentives at the cost of long-term destruction. Preserving an area of highly biodiverse tropical rainforest is made much more difficult when the same area can be cleared and used to generate profits from, say, a palm oil plantation.

And third, even when mechanisms are successfully designed in a way that generates enough cash flows to make a conservation investment more attractive than the exploitation of these natural resources, the projects are often small and not run with a commercially viable business model that can attract investors at scale. As a result, we see insufficient venture capital investments in early stages of the development of conservation programs.

Policy leadership is key. Where benefits are immediate, such as water quality, and the beneficiaries close enough, for example downstream farmers or brewers, conservations agreements can be struck directly without much regulatory intervention. More generally, however, it is predominantly the role of governments and local policy makers to give incentives to non-marketable conservation benefits through regulation and thus make these benefits accessible to investors.

If both conservation and financial benefits are clear and cost-effectively measurable, the associated cash flows have the potential to be scaled up. With scale, risk can be pooled in a portfolio of projects across countries or across asset types.

Conservation asset classes

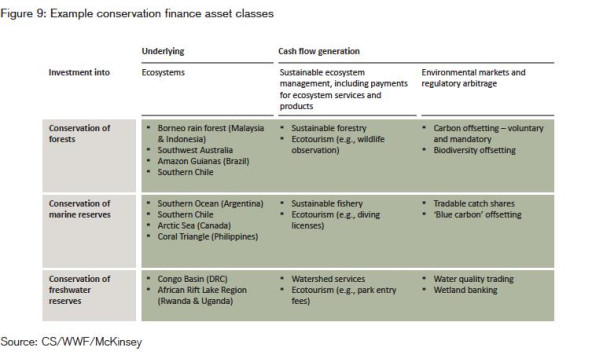

In our interviews, investors say they are looking for investable projects with clear investment characteristics, run by managers or trusted funds with conservation and financing experience and track record. The investments sort out into three simple components.

- Investments in underlying ecosystems with the goal of capital protection. The acquisition of forests, freshwater, or deserts, or usage rights tied to a long-term conservation commitment only make sense from a financial perspective if they generate a financial return and thereby become actual financial assets (though the underlying ecosystem may have intrinsic value for some investors or generate other benefits, such as tax breaks). With the option to recover the principal, or to serve as collateral for further financing, they are an attractive and easily understood investment proposition. Attention must be given to traditional use rights of local and indigenous people to prevent “land grabbing” and undue expropriations.

- Investments in the infrastructure and sustainable management of ecosystem services to achieve financial returns. These investments can create economic value under the constraint of conservation, for example with lodges and trails to foster ecotourism or solar arrays for power generation. Ecosystem services (such as watershed protection) and goods derived from sustainable forestry, agriculture, or aquaculture can also provide cash flows. Such cash flows often depend on regulatory requirements or industry certifications that support premium pricing.

- Investments in ecosystem market and regulatory mechanisms to enhance returns. These are financial instruments such as securities and derivatives, as well as corporate intermediaries leveraging regulatory requirements. Examples include voluntary or mandatory offsets, subsidized power production, or permit and rights issuance and trading.

Conservation finance mechanisms need to be simple and modular, ideally structured as combinations of investments in underlying ecosystems and cash-generating mechanisms. An investment in ownership or usage rights to a tropical forest, for example, could be combined with sustainable timber production, non-timber forest products, water sales, ecotourism, and compensation payments such as from voluntary or mandatory carbon offset markets.

Opportunities exist for financial instruments for different kinds of investors. HNW/UHNW individuals, for example, could invest in the ownership of or the rights for an underlying ecosystem, such as a forest. Our interviews showed wealth preserving investment products that provide safety and a hedge against inflation could prove very attractive to these investors. Investors will want to make sure the money they ‘lend for free’ is used appropriately and effectively.

Institutional investors might be more likely to invest into more mature mechanisms such as forest land, infrastructure such as ecotourism facilities, or renewable power generation, or established businesses, such as a certified fishery. Return-oriented products in conservation can be considered like other alternatives in terms of their risk-return characteristics, with the added benefit of a clear and certified double bottom line.

Versatile early-stage venture-type conservation investments that unlock and establish profitable business models are crucial to the effort to establish conservation finance as a mainstream asset class.

There remains a key role for public funding and philanthropy, which can be used strategically as higher-risk capital, de-risking second-stage investments and making them competitive. This could help close the ‘pioneer gap’ in capital at the risky proof-of-concept stage.

Likelihood of success

Seeing conservation finance from an investor point of view will require some hard choices. Some projects are more likely to pencil out. For example, conservation of the disappearing rainforest cover in the Malaysian part of Borneo is a high-impact opportunity that also benefits from a favorable political and regulatory system. Moreover, early conservation finance projects in the area have shown initial success.

In other critical areas, such as perhaps the West African marine ecosystem in Senegal and Morocco, high conservation opportunities are tempered by political risk and regulatory challenges.

Selecting the right targets is critical to any conservation financing effort. Our team took as a starting point the WWF’s 35 “priority areas.” Together, these ecosystems represent the biodiversity and lifeblood of the planet, from the Amazon Guianas to the Arctic Sea to the Congo Basin.

We selected high-impact ecosystems where there is also a high likelihood of success in the conservation of forests, marine reserves and fresh water. We derived a “project realizability” score based on five contingency factors: environmental regulation, political risk, private sector capacity, accessibility or remoteness, and the track record of existing conservation finance projects in the area.

It should be noted that this analysis is only a guide to where the highest potential investments are likely to be, not a suggestion that investments in these areas will necessarily provide attractive financial returns.

New roles

The shift from donor- to investor-driven financing will bring new roles for both major conservation organizations and financial institutions. Rather than designing their own financing schemes, NGOs such as WWF could serve as advisors to the investment professionals who can structure and place these projects, making their knowledge and expertise available for early-stage development of projects with scalable cash flow mechanisms.

In this new approach, NGOs would identify conservation priorities, organize and package large-scale conservation projects with clear benefits and local support, and provide a ‘seal of approval’ for the environmental impact of the projects, which investors will need as they select projects. Once projects are underway, NGOs will play a large role in measuring and verifying those impacts. NGOs can increase their influence over the selection of projects by investors by using their market power to develop conservation investment project certifications.

For financial institutions such as Credit Suisse, that means developing new conservation-related investment products tailored to the needs of their private and institutional clients. Private banks and asset managers could make conservation finance part of their standard advisory services, much like philanthropy and alternative investments are today.

Conservation finance represents a rare opportunity—indeed an obligation—for the NGO community and the financial services industry to work together closely. Each must bring their specific skills to bear in order to protecting the planet’s natural capital for the benefit of future generations.

Source: CS/WWF/McKinsey

Source: CS/WWF/McKinsey

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Fabian Huwyler, Juerg Kaeppeli, Katharina Serafimova, Eric Swanson & John Tobin.