(Illustration by iStock/DNY59)

(Illustration by iStock/DNY59)

When a charity makes a 100 percent commitment during fundraising, they promise that all new contributions will go to programming: no new administrative staff, fundraising appeals, computer upgrades, or even donation processing support. This kind of promise has been a boon for a variety of organizations because it has attracted donors who wish to know their funds are making an immediate impact. The ability to satisfy donors’ appetite for spending assurances—all with a simple-to-understand pledge—makes the commitment tempting for many organizations.

Is the 100 percent model right for you? There are circumstances for which it is well suited, but when it is misunderstood by donors it can also become a source of frustration. For example, the founder of NonprofitAF Vu Le summarized this frustration—calling the model “nonsensical, manipulative, and insulting to people whose work is considered ‘overhead,’”—observing that it can make it more difficult for high-overhead organizations to raise funds, as well as reinforcing the idea that nonprofits are “opaque and shady.” The problem is that donors often associate the 100 percent model with 100 percent efficiency, imagining that overhead funding might crowd out program accomplishments. Such a misunderstanding can create an expectations gap. And committing to devote 100 percent of contributions to programs risks setting an unrealistic standard, even perpetuating the myth that program spending is inherently better than other spending.

Charities who make the 100 percent pledge are not claiming they only spend on programs, of course; the commitment is only about what to do with extra dollars. But this commitment can be a boon for some, when communicated properly.

Matching Donor Priorities

Though it may seem counterintuitive, the 100 percent model permits an organization to match donor priorities more effectively, if done right. The organization can seek out and cultivate a subset of donors who are willing to support administrative infrastructure, administrative funders who help set the stage for the wider swath of donors whose goals center on funding programs. As with matching gift commitments, donors who underwrite administrative costs do so knowing it will make it easier for the organization to seek additional funds and scale operations.

Are you enjoying this article? Read more like this, plus SSIR's full archive of content, when you subscribe.

The source of this infrastructure support can vary depending on an organization’s funders. Direct Relief, an organization focused on providing humanitarian and medical aid, has been able to fund its 100 percent promise for emergency-response donations thanks to legacy gifts. Robin Hood, an organization centered on alleviating poverty in New York City, relies on financial commitments from its board members to cover administrative costs. And in other organizations, such as the cancer research organization Pelotonia, corporate partners help provide sufficient funding to cover administrative costs.

Academic research has confirmed that securing funding for non-program costs from a few sources first and then providing incremental donors a promise that their donations will go directly toward programs can be highly effective: The donation boost from a 100 percent commitment is more pronounced than with matching gifts. Acknowledging that such “mental accounting” is salient for many donors underscores the power of the 100 percent model in fundraising. And fund accounting practices readily permit implementation by allowing an organization to separate different funding streams for different uses.

Shifting Focus to Relevant Costs

Because many individual donors are unable to sift through an organization’s financial details, they often pay close attention to summary metrics to assess spending priorities. For these donors, the 100 percent model helps redirect the discussion toward more meaningful costs than the traditional program expense percentage metric does. The reason for this is tied to the concept of relevant costs, a key tenet of managerial accounting: For manufacturing companies, the relevant cost issue typically arises when the traditional full (absorption) cost of an item for sale does not reflect the incremental cost of producing that unit. Decisions of whether to produce another unit or what to charge for it, however, should hinge on the incremental cost, not the full cost. Much of managerial accounting focuses on providing measures of such incremental costs that are more useful for decisions.

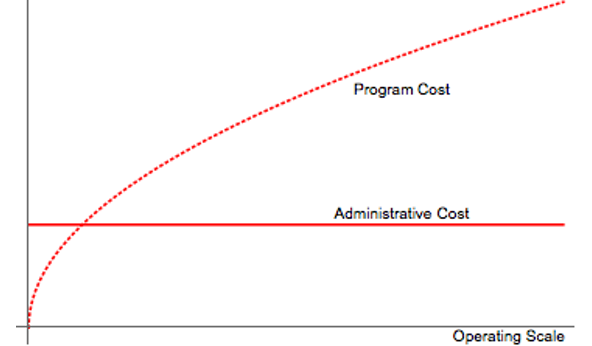

However, the issue of relevant costs also arises when examining cost behavior of a charity. Consider the following illustrative example of charity’s cost behavior as operating scale changes.

Figure 1: Cost Behavior Example

Figure 1: Cost Behavior Example

As more programming is enacted the total cost increases but the incremental cost of service provision declines, seen in the increasing, concave shape of the “program cost” curve. Economies of scale are further reflected in “administrative cost” being fixed as the organization expands its programs.

But while donors may conflate how funds are split between programming and administration with spending efficiency, the program expense ratio is not particularly meaningful in this sense: in this example it merely reflects changes in scale. An organization that shows a higher program expense ratio is only exhibiting a higher scale of operations. High program expense ratios can be a self-fulfilling prophesy, in other words, if donors provide funding by relying on program expense ratios: Organizations that look more efficient generate more contributions and thereby secure spending ratios that convey more perceived efficiency. This, in turn secures more funding. And so on.

How a donor’s incremental donation is used is a more apt reflection of relevant costs for a donor. In other words, if a donor cares what happens to their additional donation, the use of an incremental dollar is surely more meaningful than the use of an average dollar. This more pertinent incremental dollar usage is precisely what the 100 percent model prescribes, whereas standard ratios rely instead on average costs.

Refocusing attention on incremental spending by promising it will entirely be used on programming is practical only when program costs are clearly separable and can be expanded without materially adding to the administrative burden. An organization that provides grants to a specific recipient, like the Pan-Mass Challenge—whose 100 percent pledge supports grants to the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute—is well-suited for such an approach. Even when funds go to a variety of places, the 100 percent pledge is reasonable when the program spending can be focused on grants, as with the Ploughshares Fund and its support of a wide range of efforts to reduce worldwide risks of nuclear conflict.

On the other hand, organizations for whom program spending is spread among different approaches or for whom expanded scale introduces administrative complexity run the risk of the 100 percent model backfiring. This turned out to be an issue for Smile Train who once made use of a 100 percent promise: Though its mission focus on cleft-palate surgeries is clear, its mix of spending between different approaches left substantial uncertainty about what spending was represented in its 100 percent promise.

A Commitment to Future Choices

Many donors focus on historical spending by charities because they want a window into future spending. Skepticism about how their donations will be spent is healthy, as we have seen many examples of waste or mission creep as budgets expand (even among organizations operating with the best of intentions). For this reason, a popular and growing charity—that runs the risk of mission creep—can use a 100 percent commitment to reassure donors how growth will affect operations. A visible example is charity: water, an organization focused on addressing the global water crisis. charity: Water has seen substantial growth and has provided assurance to donors about future plans through its 100 percent promise, a pledge given added credence by an independent audit.

Because of the commitment it entails, the 100 percent model always presents hazards to consider. Unexpected disruptions in funding streams earmarked for administrative support or even sudden windfalls that bring added non-programming costs can bring challenges due to the limitations on spending. For example, even something as apparently minor as credit card and donation processing fees can be debilitating for an organization with a 100 percent pledge: An organization blessed with a new stream of donations may find itself scrambling to secure other funding sources to cover the costs of processing those donations. Pelotonia (which supports cancer research conducted at The Ohio State University) uses a novel approach that can help with this dilemma, presenting each donor with an opportunity to add to their donation to cover the processing fees. Not only does this provide transparency for donors about costs of processing donations, it also can help alleviate the pressures that such can fees bring to the 100 percent model.

The 100 Percent Model Is Not for Everyone

The 100 percent model is not a one-size-fits-all approach. In fact, it may only be appropriate for a small number of charities. As we have seen, organizations for whom the 100 percent model can prove helpful are those with:

- A set of donors who can be convinced to provide seed funding to cover administrative costs

- High reliance on peer-to-peer or other fundraising practices that make an extended conversation about administrative spending with all donors impractical

- Predictable and largely fixed administrative costs

- Clearly trackable program costs

- Scalable programs

- Donors who want a clear commitment to future spending practices

Those who fund research or provide a specific service to program recipients can match the profile well. The same goes for organizations that attract both general public support and foundation or corporate sponsorship. However, organizations with limited reliance on general public support, a blurred line between program and administrative spending, administrative costs that rise materially with expanded programs, or expansion plans that entail a wider scope rather than just greater scale may find the 100 percent model not to be a good fit.

Recognizing that it works for some and not others, those who use the 100 percent model should avoid creating an impression that it is a sign of superior virtue. Instead, the model reflects a particular funding mix and cost structure, one that often cannot be replicated by all other organizations. A healthy nonprofit sector has room for these different types of organizations to co-exist in a symbiotic fashion.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Brian Mittendorf.