(Illustration by iStock/Jackie Niam)

(Illustration by iStock/Jackie Niam)

In recent years, social justice leaders have consistently called for a systems change approach to redressing the root causes of social problems, rather than only mitigating their symptoms. These leaders often elucidate systems change through example, calling out important elements such as collective action, proximate leadership, research and evaluation, and policy change. But while it’s helpful to illustrate the endgame, the process for pursuing systems change remains underarticulated, and as such, we risk rendering systems change an unactionable ideal.

After all, social justice is by nature utopian. It’s defined as an equitable distribution of resources and recognition among social groups, which provides an equitable capacity for individuals to shape society to meet their needs. Nearly everyone conceives of this goal differently; what seems equitable to me may not to you. To understand what systems change is and how to pursue it, we need to connect core strategies back to the root causes they address.

In facilitating the development of systems change plans for a variety of nonprofits, I’ve found that principles associated with social justice offer a unifying framework to help staff and boards understand not only the end goal of systems change, but also the root causes of social problems and what strategies will solve them.

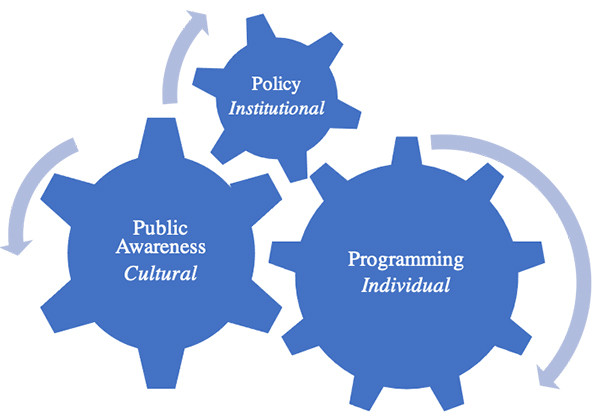

Social justice principles hold that inequity and oppression occur at multiple levels: individual, institutional, and societal or cultural. Inequity and oppression on one level reinforce inequity and oppression on the others and perpetuate systemic injustice. Systems change therefore requires that we address inequity at all three levels, which correspond generally to three types of strategies:

- Programmatic: to effect change at the individual level by shifting mindsets, including the perception of self

- Policy: to address institutional inequity, both within an institution and between institutions

- Public awareness: to change the perception of a group at a societal or cultural level

Are you enjoying this article? Read more like this, plus SSIR's full archive of content, when you subscribe.

In its simplest conception, developing a systems change plan requires that we integrate programmatic, policy, and public awareness strategies to address related root causes at the individual, institutional, and societal levels. Just as different levels of inequity and oppression reinforce one another, each type of strategy impacts the others. For instance, a program and its evaluation must generate a compelling data case, whether through quantitative evidence or qualitative stories of impact, to change policy, including by shifting public perception among those who influence policy makers. Keep in mind that policy makers are not just government officials. What a foundation invests in is a matter of institutional policy, as is university admissions criteria, for example. Proof-of-concept programs and public awareness campaigns can be designed to influence all types of institutional policy. The key is making the policy change support your programmatic solution, and vice versa. In describing this approach to a colleague, it clicked for him when he thought of a flywheel, where the activation of one strategy advances the whole. Another analogy might be a set of gears, with evaluation as the grease that keeps it all going.

Systems change requires mutually reinforcing strategies. (Image courtesy of From Charity to Change)

Systems change requires mutually reinforcing strategies. (Image courtesy of From Charity to Change)

This is why using one or two types of strategies can make an impact, but why maximizing and sustaining change requires all three. Policy change in particular is sometimes conflated with systems change, but this is misguided. New policies can fail to have their intended effect when the individuals charged with implementing them through programs haven’t internalized what the policy change means for their professional practice.

Policy change can also fail to have a long-term impact when societal attitudes don’t shift in kind. Mass incarceration offers a stark example: As civil rights lawyer Michelle Alexander documents in her book The New Jim Crow, after the prohibition of Jim Crow, policy decisions related to criminal justice and economic development compounded to reassert racial caste, abetted by racist cultural attitudes that remained intact. She argues that without a mass movement to change oppressive attitudes at a cultural level, criminal justice reform will beget yet another iteration of oppressive racial policy.

The beauty of a simple framework for understanding the causes and solutions of complex social problems is that it enables clear, cohesive, and confident day-to-day action, taken in pursuit of long-term strategies.

Systems Change Planning for Social Justice in Action

I’ve used this framework with a diversity of organizations—including cash-strapped ones and one backed by a billionaire—working on a diversity of issues, including homelessness, affordable housing, and public education. Few of them originally used social justice language to express their objectives, yet all were fundamentally working to promote greater, more-equitable opportunities for specific groups.

Of course, the framework resonates especially with those who already view the world through a social justice lens; they innately trust in the outcome, because of the principles that inform the process. This was the case for staff at the Petey Greene Program, where I facilitated a planning process after joining the organization as its second executive director in November 2019.

Starting from strength in programming. The Petey Greene Program was founded in 2008 at Princeton University to recruit college students and community volunteers to tutor people in prison. From the start, the program had a profound impact at the individual level. Most incarcerated people have no high school diploma, a reflection of the US school-to-prison pipeline. With tutoring, they receive the personalized support most anyone needs to succeed academically. As they progress, their self-confidence grows, bolstered by the commitment of volunteers returning week after week to support them. For volunteers, interacting with incarcerated students compels them to reflect on the injustice of the criminal legal system, its intersection with educational inequity, and their relationship to it. In its reciprocal impact, the program illustrates the power of programming to change the perception of self and others, challenging internalized oppression and dominance alike.

By the time I joined as executive director, the Petey Greene Program was recruiting more than 1,000 volunteers annually from 30 universities, tutoring 2,500 incarcerated students each year, in 50 jails and prisons in seven Eastern states and the District of Columbia. Yet some questioned whether the program was doing enough in the context of mass incarceration, given that the United States has a prison population of more than 2 million; Black men are incarcerated at five times the rate of white men; an additional 4.5 million people are on parole and probation; and, as a result of myriad cultural and institutional obstacles facing anyone with a criminal record, two-thirds of formerly incarcerated people are rearrested within three years.

The need to change policy and public perception. While the program encouraged volunteers to become advocates, the organization itself insisted on neutrality where policy issues were concerned. In so doing, it risked the appearance, if not the reality, of being complicit in an unjust system by alleviating its consequences but not its root causes. I would learn from my colleagues—most of whom were formerly incarcerated, had family incarcerated, or came from a community disproportionately impacted by mass incarceration—that activists refer to this dynamic as “carceral humanism,” improving the image of an irredeemably inhumane institution by proffering it as an important provider of social services.

Still, some on staff and many on the board feared that pursuing systems change could detract from programming by diffusing focus. And indeed, the way most of them conceived of it would have conflated systems change with advocacy on a host of criminal justice policies. My goal, through a scaffolded strategic planning process, was to help my colleagues understand and apply the concept of systems change through a social justice lens. Done well, adopting a systems change model would result not in a diffusion of energy from educational programming, but in a laser focus on improving, promoting, and expanding it, supported by public awareness and policy strategies. The evidence was clear: Expanding access to high-quality education is critical to decarceration. An oft-cited meta-analysis by the RAND Corporation found that people who participated in an educational program while incarcerated had 43 percent lower odds of returning to prison. The value of tutoring was also evident: A study of the Petey Greene Program’s impact showed that incarcerated students tutored by a volunteer progressed one to two grade levels more than those without access to tutoring, over the course of one semester.

Connecting programming, policy, and public awareness. To build on this promise, the Petey Greene Program had to shift from coordinating volunteers to training and coaching high-quality tutors. This required all staff to develop new skills, as well as the conservation of resources in order to add new positions that would support a systems change model. Open program positions remained vacant while we saved and shifted resources to hire for expertise in operations, curriculum, training, evaluation, and communications.

Program volunteers previously supplemented any prison education program, no matter its quality, but our systems change model required that we pilot new, more effective models of education and advocate for them as a matter of policy. We began to ask more of the correctional institutions we worked in, including consistent access to curricular resources and impact evaluation, as well as funding to sustain and expand high-quality programming. Taking responsibility for the outcomes of the system in which we worked also meant continuing to tutor people after their release from prison until they achieved their educational goals, and piloting new approaches to preventing incarceration, including intensive educational support in lieu of sentencing youth to prison. Over time, the success stories of individuals participating in these programs will help the Petey Greene Program make a compelling policy case for expanding access to education—not only while people are in prison, but to keep people out.

A Process for Developing Systems Change Plans

A social justice framework also has implications for the planning process: We can’t get to a place where individuals and groups shape society to meet their own needs by imposing on them a conception of what those needs are and how to address them—hence the field’s important and growing emphasis on proximate leadership. Those proximate to a problem understand how inequity and oppression occur at the individual level because they’ve lived it or are otherwise proximate to those who have. Not all of the people proximate to a problem may know how their perspective translates into policy or public awareness campaigns, but that’s where intermediaries come in. Intermediaries can facilitate systems redesign that centers the insight of those closest to an issue.

Here are seven simple steps to get started on developing a systems change plan:

Step 1: Clarify and define what systems change means for all stakeholders: What composes a system? Social justice principles provide a cohesive framework for understanding the different dimensions of systemic inequity, including how they are interrelated and affect each other.

Step 2: Start to identify systemic root causes by asking: Why do we need this organization, project, or initiative?

Step 3: Categorize these causes as manifestations of the problem at the individual, institutional, or societal levels. Reflect on how they interact with and reinforce each other.

Step 4: Contemplate what programmatic, policy, and public awareness strategies might address the problem at each respective level. In a world where the problem is addressed, what does policy look like? What does society understand about the problem that it didn’t before? What do individuals understand about themselves and their ability in relation to others that they didn’t before?

Applying steps one through four to the Petey Greene Program planning process, I asked staff, board, and alumni why we needed the program. Their responses included creating hope and self-worth among incarcerated people. This was evidence that the problem was at the individual level. The strategy to address it was thus programmatic, namely, supportive in-person tutoring that restores dignity and inspires academic confidence. Another common response to my question was we needed the program to address woefully inadequate education in prisons, an institutional issue requiring policy advocacy to expand high-quality education in prisons. Other responses reflected the societal conditions that perpetuate incarceration, with some responding that we needed to address educational inequity outside of prison. The program could tackle this root cause through a public awareness strategy that elevates the stories of incarcerated students and shows how most students are now pursuing their first chance at education, not their second.

Step 5: How can you prove your current or potential strategies address the root cause of a problem at its respective level? How might those strategies reinforce each other? Evaluation is important. What would indicate that one strategy has an impact on another? What evidence will be compelling to which constituencies the initiative needs to influence? For example, what program data would support a policy change with policy makers and those who influence them, whether quantitative or qualitative? If you can’t prove a strategy will achieve a specific outcome, it won’t. Remember, evaluation takes many forms, including cost-benefit analysis and randomized controlled trials where you’re assessing outcomes against a predetermined strategy, and developmental evaluation, which allows for iteration and proving out what works, why, and under what conditions.

Step 6: Identify incremental—at least quarterly—steps that take you from where you are to where you want to go. Whether you have a three-year or 10-year time horizon, identify who needs to do what, by when, for every incremental action. Any action that’s not time-bound and the responsibility of someone specific won’t get done. In addition to systems change strategies, your plan should take into consideration any operational limitations: What staffing do you need, by when, and contingent on what funding? What partnerships and by when? Systems change is impact through integration. If your strength is in programming, what organizations might you partner with to influence government or other institutional policy?

Step 7: Reflect on progress against your plan, again at least quarterly. Systems-change plans are by nature contingent. Reality will inevitably diverge, whether positively or negatively. The key is to keep going with what’s working and what conditions allow. Your other strategies will catch up when they can. That’s the beauty of a flywheel; if your strategies stay integrated, activation of one will advance the whole.

Additional Considerations in Pursuing Systems Change

While the contours and emphasis of systems change plans differ by issue and context, I’ve seen three additional commonalities in facilitating this work for nonprofits.

First, pursuing systems change will redound to your impact and your bottom line. Philanthropy is attracted to time-bound investments resulting in long-term, widespread change. For cash-strapped organizations like the Petey Greene Program, we had to retrench to restaff differently, which enabled the organization to resume growth over time through diversified revenue, including with the addition of public contracts. At another organization I led, we had near limitless resources to fully fund our systems change initiatives, but state and national foundations wanted to participate with funding and did so because of the potential.

Systems change will frighten some, but most will get on board once you start to succeed. Systems change requires that everyone do their jobs differently, whether it’s a government official who must reallocate funding to a new program; a program manager who becomes responsible for outcomes, not just outputs; or a board member who must educate himself on policy issues or feels displaced by proximate leadership. Anyone who doesn’t understand and embrace their role in supporting systems change will hinder it. It’s therefore critical to provide individuals with ample support to process, understand, and feel confident in their new role, providing both the why and the what. As they embrace it, they’ll be energized by contributing to transformational change.

Disruptive innovation alone is not systems change. Systems change eventually requires working within a system to change the system, not just creating an alternative and assuming systems change will take care of itself. This is an important distinction across all issue areas, but especially in fields where the focus is on disruptive innovation—that is, creating a solution or service for underserved consumers (like volunteer tutors for incarcerated people without access to education). While disruptive innovation is important to systems change, it should not be conflated with it. In his Harvard Business Review article “Disruptive Innovation for Social Change,” the father of disruptive innovation, Clayton Christensen, offered an often-overlooked corollary to his theory when applied to social change: While disruptive innovation can often creep upwards, impacting a market or industry as a whole, broader change is a byproduct, not the intent. As such, disruptive innovation holds limited innate public value and generates positive systemic improvement only when intentionally designed to do so.

A social justice framework for systems change planning enables any organization to pursue systems change. It also makes an inherent argument for why every nonprofit should: Short of systems change, social justice leaders may alleviate the symptoms of a social problem, but they may also perpetuate it by leaving an unjust system intact.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Alison Badgett.