There is no single, easily digestible storyline about youth voting. Millennials are the most diverse generation in American history and have grown up under conditions of economic inequality not seen in the United States for almost a century. They also vary in their political engagement and in their opportunities to engage. And because institutions and older adults lack a consistent commitment to youth voting, young people often end up participating in politics, and with civic issues in general, in ways other than voting—sometimes in reaction to what they see as political dysfunction, and sometimes because opportunities to do community service are more prevalent.

That’s why we need to pursue many coordinated strategies if we’re going to substantially increase the numbers of youth who vote in US elections.

The National Trends

On the surface, this news isn’t surprising. There has been no consistent trend of youth voter turnout decline or improvement over the past 40 years. As the figure below shows, Millennials are turning out at similar rates to the previous two generations when they face their first elections.

The "first" election was the Presidential Election in which the entire cohort of 18-24 year olds were eligible to vote. For Boomers, this was 1972. For Gen-Xers, that election was in 1992, and for Millennials, it was 2008. (Source: CIRCLE)

The "first" election was the Presidential Election in which the entire cohort of 18-24 year olds were eligible to vote. For Boomers, this was 1972. For Gen-Xers, that election was in 1992, and for Millennials, it was 2008. (Source: CIRCLE)

What’s more, the differences in youth voting rates between elections can usually be explained in terms of the amount of outreach to young voters. We find a strong correlation between the number of young people who say they were contacted in a given campaign and youth turnout, but the level of outreach is inconsistent.

The stability in youth turnout stands out, however, when you consider the massive shifts we have seen in the United States in modes of campaigning, laws, and norms governing registration and voting, and the media environment.

More important, the turnout rate for a whole generation of youth in any given election is a misleading statistic because it conceals differences among young people of the same age, which can dwarf generational changes. The biggest gaps are by education, as the figure below demonstrates. For young people, education is the best proxy for social class. Thus, the graph reveals the relentless replication of political inequality by class: More educated young people tend to turn out to vote at higher rates. Gaps by education also imply racial disparities, since people of color are somewhat overrepresented among youth with no college experience—although young African Americans have voted at relatively high rates.

There are massive geographical differences, too. In North Dakota, youth turnout hasn’t gone below 50 percent in the past 30 years, while in Texas, it hasn’t surpassed 43 percent in that same period, and it dipped to 30 percent in 2012.

These differences in youth voter turnout threaten a healthy democracy in which all people have an equal chance to have a voice.

Changes in Laws and Policies

Public policies have changed in many ways since 1972, but no institutions with significant scale (such as K-12 schools, higher education, and federal agencies) have made any concerted effort to improve youth voter turnout, as they have, for example, to increase youth volunteering.

State voting laws have also changed, but not always in ways that benefit voters. We find, for example, that allowing registration on Election Day boosts turnout, but that some restrictive provisions, such as photo ID requirements, lower it. These are contributing reasons for the enormous gaps in turnout between states.

States have also changed their requirements and expectations for civic education. Some states have increased their requirements in this area, but in doing so, they have generally shifted their focus from teaching students to engage in civic life to imparting more content about civics. Overall, the subject has received diminished attention, as schools focus increasingly on literacy, science, and math.

The turnout of low-income youth is most affected by barriers. For instance, we find that photo ID requirements only reduce turnout for non-college youth. And youth on a college track, such as those taking AP courses or attending school in more affluent districts, are more likely to be exposed to high-quality civic education practices in public schools, including being taught about voting.

The narrowed electoral and political battleground also reduces the need (and motivation) for political organizations to engage in broad outreach and develop deep membership. When, as Elaine Kamarck and others note, only some states are “in play” in an election cycle, it means that many youth are not exposed to information and interventions that would mobilize them. Political organizations are reaching out only to those who already have a higher propensity to vote.

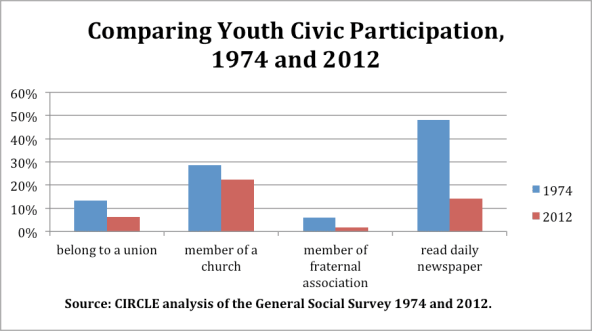

Changes in Civil Society

Not all gaps in voting rates can be blamed on public policy. The civil society built in the 20th century tended to recruit young members for non-political reasons and then make them political. Large institutions—such as unions, churches, Urban League, and Elks—had the means and motivations to recruit widely, and they had incentives to interest at least some of their young members in politics. Belonging to these groups (or subscribing to a newspaper) was correlated with voting. But as the figure below shows, all these organizations have lost youth members since the 1970s.

To be sure, there are now alternatives to these organizations that serve to empower at least some young people. No one could join a social media campaign in 1974, for example. Still, the new array of civic networks and groups have not yet shown that they are capable of boosting youth voter turnout significantly or reducing gaps by social class.

What Should Be Done?

Research shows that a range of specific reforms and interventions can make modest improvements in youth turnout. But the scale of impact from each of these proposals is too small to solve the persistent problem of low and unequal participation. There’s promise, however, in coordinated work among those engaging in the issue from different sectors.

For example, implementing same-day registration, pre-registration programs, and a voting age of 16 or 17 for local elections (which would allow high school students to learn to participate in democratic systems while they are learning about those structures) are reforms that hold promise for impact at scale.

Civic education could also become more effective and prevalent if we could show that civic skills learned in the social studies classroom have value for careers and employment. The challenge here is quelling the public’s fear that effective civic education will have partisan consequences. We found that about one quarter of high school teachers of civics and government were leery of teaching about the election in 2012 because they feared backlash from local adults. Better preparation for future teachers and professional development for current teachers would help allay their concerns, and, in turn, help them allay public fears.

There is no single quick fix. We must ask whether society supports youth engagement, and, if it does, how that support can be made equal for all youth, regardless of education, race, and income. We believe that encouraging youth to engage and to contribute their skills and values can help improve the political culture, but major institutions—educational, governmental, political, and civic—must actually want that to happen.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Abby Kiesa & Peter Levine.