(Photo courtesy of Greg Cousa)

(Photo courtesy of Greg Cousa)

Strategy strategy everywhere.

Strategy strategy, in my hair.

On my road to scale I bumped into End Game, stumbled onto Systems Change, which confused my Theory of Change.

My Mission’s drifting and my Vision’s blurry.

My fundraising “sounds” uplifting yet all I do is worry.

When it comes to developing strategy, it’s easy for a social venture’s leadership team to revert back to the same old strategic planning process they’ve used in the past: Inertia is real and repeating the same process, even if you know it’s not the best, is comfortable and easy. Why does strategy have to be so hard? Well ... because it is. Strategy is hard! It’s about the future, and—whatever any charismatic leader, politician, funder, or Burning Man-attendee might say—the future is murky, messy, confusing, and 100 percent unknown.

However, the strategic process doesn’t have to be. Even with a visionary leader, a strong brand, and clarity on future trends, good strategy will always be translucent, at best; all the indicators in the world can’t make the future fully known. But the approach to developing strategy should be transparent.

Ready? Neither am I. Let’s jump in together.

Are you enjoying this article? Read more like this, plus SSIR's full archive of content, when you subscribe.

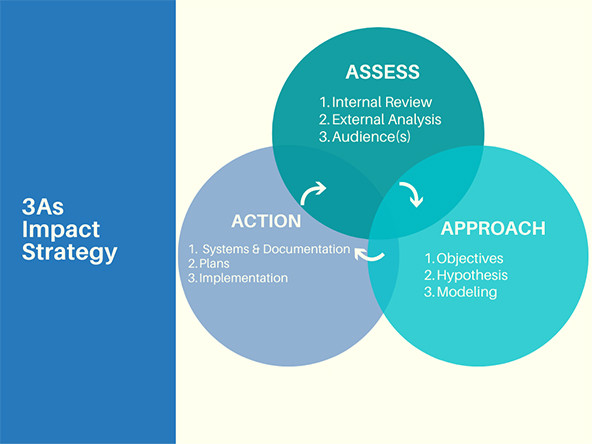

The 3 As of Developing an Impact Strategy

In my experience—both in research and application with ventures—there are three core, broad phases of developing a sound impact strategy, the 3 As: Assess, Approach, and Action.

Assess is about asking the right questions, inside and outside your organization. The absolute best thing you can do in the Assess phase is get the right questions down, both internal to the organization, and external, looking outward at the market. Then, obviously, going out and getting the best answers you can! In other words, Assess is about taking a step back to look at your organization from a bird’s eye view, in context: Why does our venture exist? What is our organization trying to accomplish all these years? How are we doing? What is going on in our market? Who have been our core clients to serve? What adjacent clients could we serve? Are there partners or competition in our sector, and how are they doing? What do the latest trends tell us about our space?

Approach is about designing the right objectives, hypotheses, and overall approach to why, what, how, when, and where you’re going to scale. The Approach you build should be based on the outputs of the Assess Phase.

Action is Jackie Chan time! It’s about adjusting your organization and detailing your plans, defining, and finding the necessary resources and infrastructure, and assessing the risk and rewards of the Approach. Most importantly, it’s about implementation. Going out and testing your strategic hypotheses, followed by adjusting your strategy based on what you learned. The adjustments should lead to further action: if the test(s) were successful, wider and/or faster execution; if the tests were not successful, contraction and/or pivots.

Strategy should be linear and circular ... but not at the same time. It’s important to follow the above steps chronologically, as each step draws from the previous one and feeds into the next, but it’s just as important to revisit previous phases in light of additional information you gather. For example, you won’t simply review the question “why do we exist?'' once at the beginning of the process; after you’ve tested a strategy in the marketplace, you need to go back and ask, in light of the pilot’s success or failure, whether it supports “why we exist” (or hinders it).

Let’s check out some phenomenal organizations’ journeys I’ve had the privilege of observing.

1. Assess

You absolutely want to start with spending deep time looking in the mirror AND looking at the world with which your venture operates. In this light—looking within and without—the priority is to develop questions to answer, both internal to the organization and external to the sector you want to work in. Some questions will be necessary for most ventures: Why do we exist? What are our Core Capabilities? How successful have we been over the past few years? Why? And some questions will be quite specific to your venture: Do we only want to focus our efforts on smart clinics?

For example, take Sistema.bio, an amazing business that develops and sells (among other things) biodigesters, a prefabricated modular package that includes a full suite of biogas appliances and connections. Basically, “organic waste” goes in, and out pops renewable biogas and organic fertilizer. It sounded magical to me, and Sistema.bio’s impact to date is just as mind-blowing: Over 180,000 people have access to clean-renewable energy and organic fertilizer; over 347,000 tons of CO2e have been mitigated; over 17,000,000 tons of waste have been treated; and over 330,000 hectares are now using organic biofertilizer ... a year.

In the early stages, Sistema.bio’s scale journey included assessing why they exist, and what makes them unique. However, this year their Assess phase has centered on more nuanced internal and external questions: What’s going on in the carbon-offset market? Should we have a carbon-offset strategy, and if so, what should it look like? How are our B2C and B2B models working in Kenya and India, respectively? What current trends in climate change policy do we see? What future trends do we anticipate in farmer migration?

Sistema.bio is one of those amazing and somehow-still-under-the-radar ventures that is knocking on the door of profitability while massively impacting thousands and thousands of people around the globe and mitigating Climate Change. Leonardo DiCaprio eat your heart out.

2. Approach

The Approach phase is arguably both the most exciting and the murkiest. It involves taking the outputs of the Assess phase and asking, “Now what are we going to do?” When you’re starting to think about scale, after all, you’ve already nailed down your product or service, you have a sound operating model and relatively stable finances, and you’ve been around the block a few times. You’re now thinking about circling other blocks. In the Approach phase, in other words, you’re thinking through big options: Do we scale geographically? Should we diversify the clients we serve? Should we innovate on our core products/services to go deeper and/or wider? (And sometimes the biggest challenge in the Approach phase is focusing and saying, “No.”)

Take, for example, The BOMA Project, an incredible nonprofit that supports small-business creation for women in the poorest parts of the world, starting with northern Kenya. Standing on the shoulders of giants—aka BRAC—BOMA iterated on proven poverty graduation models, calling theirs “REAP,” for Rural Entrepreneur Access Project. By 2016, having developed a proven model, BOMA started to ask itself some of the more common Approach questions: Why do we want to scale? What are we going to scale? How? Where? Their answer was a three-pronged approach: 1. Continue to scale through direct implementation; 2. Scale through other Big, International NGOs (BINGOs); 3. Scale through local governments.

Though not without its challenges, BOMA has definitely scaled up their impact: By the end of 2016 their cumulative impact was ~69,000 people graduated out of extreme poverty via women’s small businesses. Fast-forward five years to the end of 2021, and BOMA’s cumulative impact was over 350,000 individuals, a factor of five. Hockey-stick scale? Not quite. Not yet, but they’re getting there. The BOMA Project’s 2027 impact goal is a factor of ten on their 2021 impact: aiming to lift 3 million women, children, youth, and refugees out of poverty by 2027. Grab your ice skates BOMA squad.

In the social sector, the focal point of a scale strategy is about crafting a robust, well-articulated hypothesis to test. For BOMA, the hypotheses for larger-scale scale looked like the past strategy in some ways: new locations, direct implementation, strategic partnerships, and government adoption. But it looked nothing like the past strategy in other ways: innovating on the core model to test a few key hypotheses:

- Condensed REAP: Testing a shortened, 16-month (from 24-month) intervention, aiming to improve cost efficiencies and the scalability of their graduation model, while still achieving the same, or similar, results.

- Youth REAP: BOMA looked at its addressable market—much of sub-Saharan Africa—and saw the growing issue of youth unemployment and decided to see if iterations on its core model could help.

- Green REAP: BOMA saw the negative impact of climate-change firsthand on its existing client base and decided to start a climate-smart adaptation of BOMA’s approach, specifically supporting women and youth to create viable green enterprises.

(In addition, BOMA is testing out a nutrition-based REAP model, and another focused on refugees.)

What I love about the BOMA Project is that because they see the need they are focusing on—extreme poverty—growing, they felt now was the time to be more ambitious by testing out new approaches. In the worst-case scenario, new approaches might have a nominal impact—but with tremendous learning—while in the best-case scenario, they would see the organization diversify who they serve and how, leading to all kinds of new opportunities, stories, and of course, large-scale impact.

3. Action

Ironically, if the Approach phase is the most exciting, the Action phase can be the most boring. Buckle up and get ready to sleep if you’re a big-picture entrepreneur: The Action phase is where the rubber meets the road. The focus in the Action phase needs to be building out and testing your Approach, with the focus on actual implementation.

But as Benjamin Franklin once said, “failing to prepare is preparing to fail.” At the beginning is “pre-implementation,” the boring, nuanced, incredibly critical part where a venture builds out the key components of the operating model from the previous phase, based on the venture’s hypotheses for scale. Most big-vision CEOs and Founders at this point would rather stick their face in a bucket of hot sauce eyes-wide-open than drill down on infrastructure needs and further develop the three “P” headed snake: Policies, Processes, and Procedures. I hate to say it, but these are the backbones of what makes a venture scale successfully.

A good example is the Meltwater Entrepreneurial School of Technology (MEST). Headquartered in Accra, Ghana, MEST is a pan-African, technology-focused training program, seed fund, and venture incubator and accelerator. Founded in 2008 on the philosophy that talent is universal, but opportunity is not, MEST initially set up an Entrepreneur-In-Training (EIT) program, which provides deep software and entrepreneurship training to Africa’s top talented youth. The end goal of the EIT training program for participants is to launch a software startup, so MEST also created an incubator and seed fund to provide a launchpad for these nascent ventures in the form of seed capital and technical support. (I’ve had the pleasure of working at MEST for the past three-four years, getting the inside-out opportunity to help the organization scale.)

The 2019 EIT class had over 5,000 applicants for 60 spots. (Making it harder to get into than Harvard. Just kidding. But not!) Additionally, MEST was getting demand from ventures across the continent, who were asking if they could pay to join our incubator. The problem was MEST was a “closed circuit”: You needed to get into the EIT program in order to get the opportunity to become accepted into the incubator. At this point, we discussed the need, desire, and opportunity to scale. This was when the quick Assess work took place for MEST, looking at who we are, who we’ve been, what’s going on in our market, and who our target audience is. On the latter, this was critical, and we were clear that we had three broad target audiences: 1. Un-, or under-employed Young Africans; 2. Startup/early-stage ventures; 3. Scale-stage ventures.

From here, in the Approach phase, we were clear that we wanted to scale to reach more young Africans and ventures, we knew we had a lot of assets and expertise in house to leverage as we scaled, we had clarity that we wanted to start ASAP, we knew that we wanted to first test our pilots in MEST’s home country of Ghana, and finally we developed the high-level strategic hypotheses and design on three new pilot programs to test. While the lessons, ideas, and challenges for MEST were based on deep, years-long operations, the initial strategic hypotheses were not overly complicated or massively researched, and yours don’t need to be either. We came up with the initial three new strategic hypotheses in a few hours: Pre-MEST, MEST Express, and MEST Scale:

- Pre-MEST would aim to scale key elements of our training program to help MEST scale its impact from reaching ~60 Africans a year, to reaching hundreds of Ghanians annually, en route to 1000s across the continent.

- Where our historical incubator would support ~10 startups a year across the continent, MEST Express would aim to accelerate 30-40 startups in Ghana alone each year.

- And finally, MEST Scale, in some ways our most ambitious program, aimed to support later-stage, growth-ready Small or Medium Sized enterprises (SMEs) on their scale journey.

While the initial strategic hypotheses came within a single day, we spent months building these out to test. We decided very early we didn’t want a bloated NGO with 10s of 100s of offices around Africa. As such, for Pre-MEST and MEST Express, we knew a part of our ability to sustainably scale long-term would require our need to work with other Entrepreneur Support Organizations (ESOs) in other parts of the country we didn’t operate in, nor knew the local context. We were after scaled impact, not a scaled organization. In addition to implementing partners in the form of ESOs, we knew we also needed a network of different partner types: Implementing partners, mentors, experts, investors, researchers, and funders. On the latter partner, we found a great-fit partner in the Mastercard Foundation’s Young Africa Works strategy, who provided timely capital, flexibility, and thought-partnership.

When the plans were set, contract was signed, and the excitement levels were more bubbly than a champagne factory, I flew out to Ghana in February 2020 to start the Action phase of the strategy work. We scaled perfectly, and everything went exactly to plan. Thanks for reading!

Just kidding.

The next month, this horrible thing called COVID-19 was declared a global pandemic by the World Health Organization, and just like the rest of the world, everything came to a grinding halt. The wind was knocked out of our sails, but the Mastercard Foundation encouraged us to move quicker to help young people and startups—already facing massive barriers—weather COVID-19. When we launched a few months later, with our cobbled-together programs, we not only had impact, but we exponentially increased our learnings as a program team much faster than if we had stuck to our original timelines and plans. We did it by spending a lot of time building the right infrastructure, including rolling out new systems, creating the necessary policies, processes, and procedures, assessing the risks that we anticipated, and dealing with the ones we didn’t.

The absolute best part of the Action phase was building the team needed to scale. And so the silver lining with COVID-19 was that it allowed us to pull staff from MEST’s training program to our three new programs given our postponing the 2020 EIT program class. These key folks were critical in providing institutional knowledge, leveraging key partnerships, assuring some level of organizational cultural continuity on the new programs team, and catalyzing the much-needed, and still challenging, integration of our new work with our existing work. The new organizational structure reflected MEST’s legacy while accounting for the new expertise and capabilities needed to scale.

After over two years of pilots, with some challenges knocked down, and others still being worked through, the programs have largely exceeded our lofty expectations. We are on track, or have already, exceeded the high-impact targets we set for ourselves three years ago: Roughly 400 young Ghanaians have found dignified and meaningful work, over 60 startups have been accelerated leading to an additional 500+ jobs created, and over a million dollars in additional investment has been raised.

As the ink dried on the chapters of 2021, and 2022’s first pages turned, we spent some time reviewing, reflecting, and thinking about what holds for MEST in 2023 and beyond, given the challenges and successes of our three new programs, coupled with our ambition for larger-scale impact, quicker. Like a veteran climber, MEST is looking for bigger mountains to climb in Africa, seeking to scale our impact across West Africa in the next few years, with a determined eye to the southern and eastern parts of the continent thereafter. As with a good education, the more we’ve scaled, the more we’ve learned, and the more we’ve learned, the more we realize that we don’t know, but want to go figure out.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Greg Coussa.