(Photo by iStock/ArtRachen01)

(Photo by iStock/ArtRachen01)

Good ideas deserve to scale. But scaling without efficacy can have severe consequences. When funders see promise in grantee work—but underestimate what it takes to grow responsibly—they can find themselves encourage promising initiatives to grow too quickly, to the detriment of programmatic efficacy, operational capacity, and sustainability.

For example, when a youth financial literacy program showed promising early results—high student attendance and satisfaction—but had little hard data about financial literacy gains, a funder urged them to expand from to “10 cities in 10 years,” adding a new city each year. However, when the program expanded to a second site across the country, they discovered that the organization hadn’t truly codified the program model. Even worse, they didn’t have enough program data to understand what was working (and not working) in the original or new site. After a few years, the program folded. Imagine if the organization had, in fact, expanded to 10 cities in 10 years without first codifying their model!

It is, of course, true that under-resourced early-stage organizations—especially those rooted in communities of color and other historically marginalized communities—may lack opportunities to research, prototype, and pilot programs, as well as the ability to develop initial “proof points” to codify what works before scaling. But the key to scaling successfully is planning for the long road ahead. Efficacy requires demonstrating compelling and replicable results, as well as codifying what works: specific programmatic and staffing requirements, program frequency, dosage, duration.

Attaining efficacy is a prerequisite to successful scaling and a necessity for long-term organizational stability. But budding organizations are less likely to reach their goals by increasing program efficacy and scale simultaneously, let alone scaling prior to demonstrating efficacy (as with the “10 cities in 10 years” mistake cited above). Organizations should focus deeply on efficacy first—at a smaller scale and, potentially, for a long time—before scaling up.

Are you enjoying this article? Read more like this, plus SSIR's full archive of content, when you subscribe.

From Small to Great

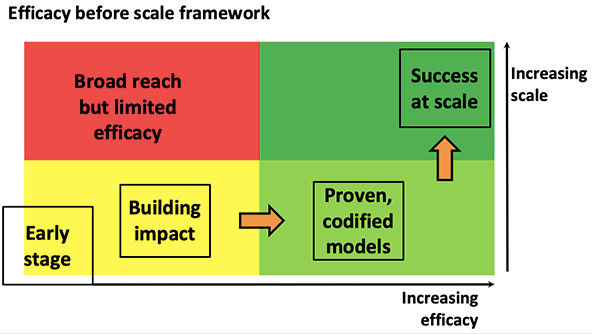

To support organizations considering their scaling journey and ambitions, and to help leaders plan for meaningful and impactful growth, we developed an “efficacy before scale” framework in 2014—first developed by Public Equity Group as part of an engagement with Tipping Point Community in 2014—outlined in the visual below:

The organizations we highlight later in this article generally started small, took considerable time to demonstrate strong results, and only then scaled their work, much later, after systematically studying what led to impact, by narrowing programming, and/or through rigorous methodology and iterative testing.

The key to this “efficacy before scale” approach is a three-step process.

- Build the prototype to demonstrate (early) results: Experiment, test, and refine programmatic approaches based on evidence, feedback, and clear metrics

- Refine and “prove” the case: Codify the model to determine which elements can and must be replicated, guided by data and metrics, and develop “proof points” to show significant impact with chosen populations or target areas

- Plan to scale: With clarity on effectiveness and replication, develop plans for expansion, replication, and/or dissemination, built on strengths of the refined model

It is often challenging for early-stage nonprofits to focus on efficacy first (and stay relatively small), given the significant commitments of time and resources required to demonstrate success. Dedicated resources are needed to identify, codify, and isolate the actions and conditions that drive excellent results. Moreover, codification (in the form of a step-by-step program model, replication guide, or toolkit) should be in place long before scaling, replicating, or sharing program models and investing in the organizational infrastructure needed to support growth. Unfortunately, few funders are willing to invest in the internal learning and evaluation capacity necessary for programs to achieve and demonstrate efficacy, preferring to invest in the programs themselves—but not the work to make programs truly effective. We hope more funders reconsider this hesitancy to fund learning and evaluation and the underlying general operations capacity they require.

The organizations that have taken (and been afforded) the time and resources to develop prototypes and pilots, achieve proof points, and codify those successes, are better able to scale and maximize their impact, while also scaling their supporting infrastructure and organization, as appropriate. The case examples from three organizations, outlined below, demonstrate the value of proving effectiveness before scaling, with each organization representing a distinct, though complementary, pathway.

Three Pathways to Scaling With Efficacy

1. Piloting: Experiment and refine core programmatic work at the outset, observing, refining, and paring back, as needed.

Founded in 2007 in San Francisco, Mission Asset Fund (MAF) formalized a culturally relevant lending circle model while giving clients financial education and helping them to build credit, free of charge. In 2008, MAF began piloting, testing, and refining the lending-circle model in San Francisco’s Mission District, a historic immigrant gateway community where 44 percent of households have no credit histories. Rooted in tradition, the model formalized social loans among low-income, under-banked individuals that were previously informal and unreported. The program helped participants build their credit scores, learn to use credit, increase their overall financial security, and save for long-term goals. By 2013, 1,111 clients had participated in the program.

How to scale this model? In 2013, MAF’s founder, Jose A. Quinonez, conducted an evaluation of the local program to learn which attributes made the model so successful. “Scaling Lending Circles was not easy by any means,” he explained; “It took a significant amount of time and focused effort to make it happen. We went through a lot of iterations of the program to get it right ... We tested different aspects of the program locally before replicating it in other communities ... So we deliberately invested in technology that could facilitate our vision for scale. With the right tools on hand, we were ready to grow.”

Deciding on a network approach, Quinonez stripped the bespoke elements of MAF’s program and built a back-end technology platform for loan processing and servicing. In the scalable model, partnerships with traditional financial institutions enabled MAF to process the loans and distribute payments electronically. The payment activity is recorded and reported monthly to credit bureaus, thereby enabling participants to establish or improve their credit scores in the process. MAF not only secures the loans, in case of defaults, but also provides technical assistance, guarantees, and oversees back-end functions. The partnering agencies, rooted in their communities in each geography, provide the front-end functions—they conduct the client outreach and recruitment, facilitate the lending circle formation and orientation, and provide financial education to support participants.

MAF now operates in 18 states and Washington, DC, as well as partnering with over 40 nonprofits. Not only has this partnership strategy allowed MAF to scale its lending program, but it also enabled the organization to expand the number of individuals reached in a resource-efficient way and achieve much greater impact than the organization could ever have attained on its own.

2. Testing: Test and evaluate activities, and measure and refine approach before or during implementation.

Working America (WA), the political organizing arm of the AFL-CIO, tests its approaches and messages using experimental designs before deploying campaigns to convert “persuadable” voters. In this way, WA engages in rigorous and rapid testing and refinement at the program and campaign-levels before scaling each new voter canvassing or digital messaging program.

Founded in 2003—using Ohio and Washington as pilots—WA’s initial goal was to build “density” in union-heavy communities, to increase the scope of AFL-CIO’s political program. By the 2008 election, WA had signed up over 2 million members with 27 field offices all over the country. In 2011, WA conducted an experiment with the Analyst Institute (AI), a leading analytics institution in the progressive movement and the first time their “persuasion effect” was externally evaluated and validated. But, over the years, WA has conducted more than 150 small, randomized experiments and partnered with AI to look at their historical experimental data—combining six years of experiments—to predict which voters were the most likely to shift their opinion to vote for the progressive candidate when a WA canvasser had an in-depth conversation with them.

In 2015, WA developed its “Experiment Informed Program” (EIP), still in effect to this day, where small-scale testing leads to model-building and then scaling. “Everything in the world is a logistics question,” Matt Morrison, WA Executive Director, explained in an interview, “you have to go full-funnel in your logistics to understand the interdependencies of each step and how much you optimize each component. We are in constant learning on our management systems and the causal effects. We became able to learn rapidly and apply this to a campaign environment. We needed to validate our models, track persistence of treatment effects, combine insights across our experiments—this allowed us to develop comparative analytics.”

Although campaigns to win swing voters are rarely successful, WA’s approach has yielded results. Working America “conducted experiments in 2016 that found surprising pockets of voters persuaded by their messages. It then targeted these voters more intensively going forward and stopped talking to the voters who reacted negatively. It’s a powerful approach. From validation studies, we estimate that Working America’s changed targeting generated many thousands of additional votes. These votes would have taken many millions of dollars to capture with other tactics. These so-called experiment informed programs (EIPs) thus offer data-driven targeting recommendations that perform better than campaign gurus’ current recommendations based on polling, focus groups or gut instinct.”

3. Iterating: Codify the model through repeated, multi-year testing to develop “proof points” that are scaled with intention

The industry gold standard for evidence-based impact is Nurse Family Partnerships (NFP), a community health program whose model, based on more than 40 years of evidence from Randomized Control Trials (RCT), convinced President Barack Obama’s administration to invest significantly in their approach.

The story begins in the early 70s, when David Olds initiated the development of a nurse home visitation program for first-time mothers and their children. Over the next three decades, he and his colleagues continued to test the program in three separate RCTs with three different populations; 14 follow-up studies tracking program participants’ outcomes across the three trials have been (and continue to be) conducted.

As a strategy for scaling, they developed the “National Center for Children, Families, and Communities,” which serves as the organization devoted to replicating its program in new communities, based on the model tested in the trials. The national replication work revolved around three major functions: 1. Helping organizations and communities become prepared to conduct and sustain the program over time; 2. Training nurses and providing them with structured guidelines to enable them to conduct the program with a high level of clinical excellence; and 3. Research, evaluation, and quality improvement activities designed to continuously improve the program and its implementation. The evidentiary foundations of the NFP model remain among the strongest available for preventive interventions offered for public investment while serving over 340,000 clients in 40 states and tribal communities since replication began in 1996.

Models to Follow

Each organization ultimately achieved tremendous growth and impact in their sectors, but all took the time to develop thoughtful plans for measuring and codifying their work. The lessons for nonprofits and funders should be clear: Invest in and grow promising organizations and programs in a way that promotes efficacy prior to significant scaling and expansion. Start by building, refining, and landing the model; then, determine which components need to be replicated by codifying the model and tracking key metrics; and then, ideally with “proof points” in hand, plan to scale in a sustainable and impactful way.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by John Newsome, Aneesha Capur & Igor Rubinov.