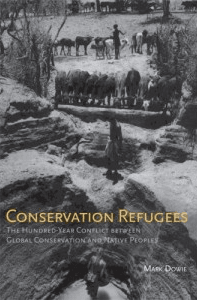

Conservation Refugees: The Hundred-Year-Conflict Between Global Conservation and Native Peoples

Mark Dowie

341 pages, MIT Press, 2009

In October 2003, Sayyaad Soltani, the elected chair of the Council of Elders of the Qashqai Confedertion in Iran, gave a plenary speech to the World Parks Congress in Durban, South Africa. He spoke of the relentless pressure on his nomadic pastoral people in the 20th century: “Pastures and natural resources were seized from us by various governments. Our migratory paths were interrupted by all sorts of ‘development’ initiatives, including dams, oil refineries, and military bases. Our summering and wintering pastures were consistently degraded and fragmented by outsiders. Not even our social identity was left alone.”

This speech, cited at length in Mark Dowie’s thought-provoking book Conservation Refugees, tells a story that is, tragically, repeated by indigenous people the world over. For centuries, governments, adventurers, settlers, and corporations have thrust aside anyone who stood between them and the resources and territory they craved.

In Dowie’s version of this story, however, the villains are not big business or corrupt governments, but biodiversity conservationists. Those driven by the desire to protect biodiversity inevitably find themselves trying to do so in the remaining areas of undeveloped land, which is almost everywhere occupied by people making their living by hunting, gathering, grazing livestock, or farming. In their enthusiasm for nature, conservationists have too often ended up riding roughshod over human rights.

In particular, Dowie targets the conservation “bingos” big, international, nongovernmental organizations), a group of ve philanthropic organizations: Conservation International (CI), the Nature Conservancy, the World Wide Fund for Nature, the Wildlife Conservation Society, and the African Wildlife Foundation. Together, these organizations control budgets of many hundreds of millions of dollars. They are also conduits of billions of dollars more from bilateral and multilateral aid donors such as the World Bank, the European Union, and the United States Agency for International Development. The bingos’ scientific expertise, their capacity to plan and implement projects on the ground, and their ability to conjure up vast investments make them agencies of great power.

Dowie is something of a doyen of the global anticonservation movement, following articles in Orion magazine in 2005 and in the Stanford Social Innovation Review in 2006, which indicted the bingos for their close and cozy links with corporate interests and their uncaring and destructive impact on indigenous people. In Conservation Refugees, Dowie returns to the fray. In alternating chapters Dowie describes the displacement of a range of different peoples (including Maasai, Ba’Aka, Basarwa, Mursi, and Karen) with brief descriptions of field visits and interviews. These are curiously lackluster accounts, highly romanticized, and surprisingly vague about the specifics of human or environmental history, but their cumulative force is indisputable. In between, Dowie offers sharp summaries of the strange world of international conservation, including the American obsession with “wilderness” and the associated need to “protect” nature by keeping local people out (but, too often, letting scientists, tourists, timber concessionaires, oil or mining companies, and corrupt politicians in).

Whether conservation is, as Dowie argues, Public Enemy No. 1 for indigenous people, is more difficult to judge. At various points he quotes very large but highly speculative figures for the total number of people displaced from protected areas (a lack of good data makes it hard to know the real extent of conservation displacement). And it would be a mistake to focus so much blame on conservationists that it distracts attention from the very real harm caused by corporate and government enclosure of rural land for commercial purposes.

The case against conservation is not novel— books like Marcus Colchester’s Salvaging Nature, published in 2002, for example, have traversed this terrain before. The difference now, perhaps, is that Dowie sees glimmers of light at the end of the tunnel, citing places where relations between indigenous people and conservation have improved (for example, in relations between the Kayapo and CI in Brazil), and where the rights of indigenous peoples have been upheld (for example, in the legal decision in December 2006 that the eviction of the San from the Central Kalahari Game Reserve in Botswana was illegal). Times are, perhaps, changing.

This is, as Dowie is at pains to say, a “good guy vs. good guy” story—very often, Western indigenous peoples’ activists vs. Western conservationists, both speaking for their clients with passion and good intentions. Despite the clogged arteries of corporate conservation, new partnerships must be possible. Although Dowie remains suspicious, and the international indigenous peoples movement activists he quotes are even more so, it is possible to imagine conservation taking full account of human rights. But as this book makes clear, a lot will have to change if this is to happen.

Bill Adams is Moran Professor of Conservation and Development in the Department of Geography at the University of Cambridge. He is the author of Against Extinction: The Story of Conservation, and co-editor of Decolonizing Nature: Strategies of Conservation in a Post-Colonial Era.