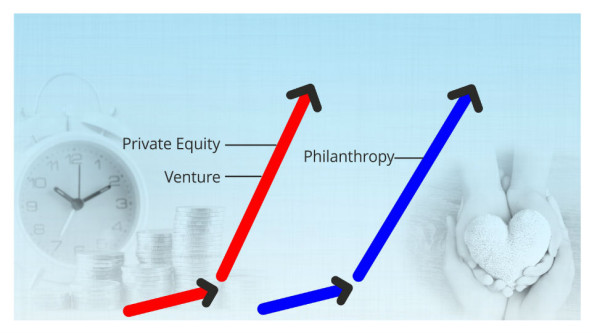

Philanthropy could follow the same growth curve as private equity and venture capital have. (Image courtesy of Jeffrey Walker)

Philanthropy could follow the same growth curve as private equity and venture capital have. (Image courtesy of Jeffrey Walker)

One of the biggest challenges nonprofit leaders and organizations face is the gap between the philanthropic aspirations of the world’s wealthiest people and their actual giving. The ultra-wealthy say they want to donate their assets to help solve the world’s most pressing problems, yet worthy programs and projects often struggle to find funding.

In a recent article, Bridgespan Group executives Susan Wolf Ditkoff and Alison Powell summarize the problem this way:

In the United States alone, more than 140 billionaires have signed the Buffett-Gates Giving Pledge, committing to give half of their wealth to philanthropy during their lifetimes or upon their death.

Despite such aspirations, our analysis shows that ultra-wealthy American families donated just 1.2% of their assets to charity in 2017. That falls considerably short of average, long-term investment returns on assets. Compare 1.2% to the S&P 500’s 20-year, average annual returns of 9%, for example. The clear-eyed math shows that if an ultra-wealthy family wanted to spend down half its wealth in a 20-year time frame, the family would need to donate more than 11% of its assets per year—a tenfold increase over average current levels of giving.

The Forbes Billionaire list shows 2,153 billionaires from 72 countries have a total net worth of about $8.7 trillion. If they gave away 10 percent of those assets annually, the flow of funds would total $870 billion a year. Contrast this with the Bridgespan giving rate figure mentioned above of 1.2 percent which results in $104 billion of giving a year. How can we bridge this $766 billion giving gap?

I believe there’s a powerful model available from a different financial sphere—the world of private equity (PE) investment. I’ve worked in PE since 1983, and I’ve seen it grow from a collection of fewer than 50 funds managing some $200 million in capital to a dynamo of more than 2,000 funds managing more than $600 billion—a three-thousand-fold explosion. It happened because wealthy families realized that they needed professional tools and support structures to better manage their investments, and that access to those resources required pooling their funds. The same compelling logic has the potential to transform the world of private philanthropy, dramatically increasing both the moneys available for nonprofit activism and the positive impact of philanthropic giving.

Are you enjoying this article? Read more like this, plus SSIR's full archive of content, when you subscribe.

The Emergence of Private Equity Funds

For many years, the Rockefellers, Morgans, Berwinds, Vanderbilts, and other wealthy families bought and held companies privately. After World War II, they began to set up teams of investment professionals to find deals and manage them. The Whitneys used this method in the 1940s when they invested in Florida Foods (creators of Minute Maid orange juice); the Rockefeller Brothers used it to invest in McDonnell Aircraft; and decades later, in the 1980s, the Bill Simon/Ray Chambers team used it when they purchased Gibson Greetings in one of the first leveraged buyouts.

These investments were successful, but the funds involved were relatively small. As investment volumes grew, so did the need for full-time, professional teams to research business opportunities, negotiate and close deals, and then track, guide, and exit the investments while adding value to the companies under management. It became advantageous for multiple families to create common investment pools, which became the first venture capital and leveraged buy-out funds—later known as private equity funds.

Over time, larger, more professional private equity businesses emerged, with whom the wealthy families couldn’t compete. Instead, those families began to invest through the new PE funds. The PE industry then began offering funds specializing in particular industries (such as health care, tech, media, industrial, or consumer), geographies (including the United States, Europe, China, and Latin America), and deal sizes. Focused on pursuing higher rates of investment return, these specialized PE funds enjoyed the competitive advantage brought by deeply experienced and knowledgeable teams of experts. These teams acted as both investors and company operators, and concentrated their efforts on specific types of investments rather than portfolios of miscellaneous holdings. The pooled PE funds also enabled wealthy families to own shares of many more companies than they could reasonably select and manage on their own.

The New Wave of Philanthropic Funds

Today a similar evolution is taking place in the world of philanthropy. Wealthy individuals and families, eager to donate moneys in ways that are focused and effective, are increasingly supporting pooled philanthropic funds, such as the END Fund, Freedom Fund, New Profit, Blue Meridian, and Co-Impact. Like PE funds, these philanthropic funds are focused on specific objectives—for example, the sustainable development goals (SDGs) established by the United Nations. Like PE funds, they are managed by experienced, knowledgeable leaders who can apply the most current knowledge of impactful program design to their investment decisions. And like PE funds, they allow wealthy families to channel their funds to a larger number of organizations than they could reach if they tried to seek out one well-run, effective nonprofit organization at a time.

There are other similarities between PE funds and the new philanthropic funds as well. Just as venture capital funds focus on identifying and developing startup businesses built on innovative concepts with high growth potential, there are now philanthropic funds that focus on supporting great new ideas from top social and system entrepreneurs. This has been a core strategy of groups such as New Profit, Draper Richards Kaplan, Ashoka, and Echoing Green. New Profit, in particular, has been investing in social change for 20 years, and has supported the growth of nonprofits like Teach for America, Kipp Schools, and City Year. Much like venture capital funds, philanthropic funds like New Profit install staff members on the boards of the organizations they support, where they spend three to five years adding value through the counsel, management insights, and useful connections they provide. They then exit the boards, having helped build the organizations to the point where they are self-sustaining and on a growth trajectory.

Continuing the comparison, just as the financial industry created growth equity funds in the private equity world, we are seeing similar innovations in large-scale philanthropy with funds such as Blue Meridian, Co-Impact, Aligned Intermediary, and the Energy Foundation. And just as there are focused industry and geography private equity funds, there are also now problem-focused funds such as the END Fund (combatting neglected tropical diseases) and the Freedom Fund (reducing the number of people held in slavery around the world).

Given these similarities, it’s no surprise that many of the new philanthropic funds were first funded by private equity and venture investors. For example, New Profit is housed in the offices of Bain Capital and enjoys funding from private equity professionals associated with Bain, Greylock, JPMorgan Partners, and many other firms. Those PE professionals are now applying the model that has worked for their investments to their philanthropy.

In addition to making grants to well-run individual nonprofits, problem-focused philanthropic funds may engage in programs like funding awareness programs, partnering with selected governments, and employing professional tools like system mapping, data tracking, and local partnerships in pursuit of their goals. For example, the END Fund recently announced a focused fund to end river blindness and lymphatic filariasis in seven countries in Africa and the Middle East. Known as the Reaching the Last Mile Fund, it already has core commitments from His Highness Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, the Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi; the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation; and other funders.

Other interesting efforts to experiment with forms for philanthropic funds include The Audacious Project, a contest sponsored by the TED organization that is encouraging nonprofit innovators to submit bold, multi-year plans in hopes of winning funding; the MacArthur Foundation’s 100&Change, which offers a single, $100 million grant to a proposal aimed at tackling a significant problem; and Blue Meridian, a project of the Edna McConnell Clark Foundation in partnership with the Bridgespan Group, that focuses on supporting projects designed to help inner-city youth.

Six Areas in Which Philanthropic Funds Can Learn from PE Professionals

As I’ve explained, philanthropic funds are already successfully implementing some of the best insights from the world of PE. But there are a number of specific areas of practice in which they can do more to benefit from the experience and accumulated wisdom PE professionals have to offer. There are also areas in which the two kinds of funds have important differences investors need to recognize. The better philanthropic funds can get at mirroring the most powerful practices of PE funds, the more success they’ll have in eliciting generous investment support from the world’s wealthiest philanthropists.

1. Measurement of results. The success of PE funds is generally measured in two ways: 1) investment returns compared to those achieved by similar funds, and 2) value added compared to passive holding of investments (known in finance as “adding alpha”). Clear, objective success measures for philanthropic funds are equally important, though often more complex. Consider, for example, the global campaign to eradicate malaria, which has been the focus of a wide array of organizations. Private donors eager to measure success in this effort established the African Leaders Malaria Alliance (ALMA), a data-focused group that tracks the performance of all the organizations focusing on combatting malaria. In addition to counting deaths from the disease, it measures the degree of improvement achieved for each dollar invested.

Independent organizations can play a useful role in developing and applying sound metrics. In the PE industry, several organizations compile data comparing performance across funds, including the National Venture Capital Association, and commercial database companies like Prequin and Pitchbook. It’s reasonable to believe that the universe of philanthropic funds might benefit from the availability of more independent measurement of results like the system ALMA uses for malaria. Who might provide that kind of independent monitoring and evaluation?

Finally, looking at return on investment as a return on social investment can help draw more philanthropic funding. In the malaria world, for example, organizations can measure the return on dollars invested in mosquito bed nets against lowering health costs and increasing a country’s 10-year GDP. The result has been a 15-to-1 payback. There are also other innovative ways of looking at social return, such as the impact multiple of money, defined as the financial value of the social and environmental good that is likely to result from each dollar invested. The Rise Fund uses this method, as detailed in the Harvard Business Review article, “Calculating the Value of Impact Investing.”

2. Management expertise. Most PE funds are managed by teams of partners with strong financial and operational track records, who have built deep deal networks and in-depth industry and/or geographic knowledge. Philanthropic funds, especially those focused on particular problem areas, need to develop management teams with similar skill sets and backgrounds. This is beginning to happen, but very few of philanthropic fund managers have a deep track record of system change. For instance, just as some successful company CEOs have moved later in their careers into private equity, we’ve begun to see some of the most successful social entrepreneurs move from leading individual nonprofits into roles as orchestrators and system change leaders. Two examples are Wendy Kopp, who has moved from Teach for America to Teach for All working across 42 countries to support leadership in education, and Rebecca Onie, who has moved from Health Leads to a health initiative focused on scaling their ideas across the United States. Creating more experienced teams—such as those that run the END Fund, New Profit, and Blue Meridian—will increase donor trust and confidence, and lead to larger and longer commitments. As this trend continues, the skill level and knowledge base of philanthropic fund managers will continue to improve.

3. Financial and psychic rewards to management. Even modestly successful PE professionals have a good chance of becoming individually wealthy. Most fund partners share 20 percent of the profits generated over a 5- to 10-year maturation period, which provides a strong incentive for commitment to long-term success. By contrast, philanthropic fund managers generally receive a salary and occasional bonuses that are focused on the short-term, since most grants last only one to two years, and they almost never have the opportunity to build individual wealth. This may be culturally appropriate for nonprofit professionals. But the field needs to find some way to ensure that philanthropic fund managers feel well compensated and motivated, either financially or psychologically, in ways that are aligned with the long-term goals of their organizations.

The legal and fee structure of a fund certainly plays a role in incentivizing management. In the PE world, investors pay a management fee (typically 2 percent of assets managed) that covers the costs of the management team while they look for deals, serve as board members, and develop an exit strategy. In the philanthropic fund space, a similar management fee structure could help motivate team members to make multi-year commitments to managing a fund.

4. Donor involvement. Investors in PE funds are generally passive. They receive quarterly reports, are invited to attend an annual meeting, and occasionally have the opportunity to speak to the investment fund partners. Donors to philanthropic funds often desire a greater degree of involvement. Those who feel a strong sense of engagement with the specific problem the fund is tackling and have significant personal knowledge of the issues involved may want to participate in discussions about problem-solving strategies. These discussions may be valuable to both the fund managers and the nonprofit organizations the fund supports.

This more-active involvement in philanthropic funds can be a very good thing, so long as donors just provide advice and are not active in the fund’s day-to-day management—an important balance to maintain. The Generosity Network, a book I co-authored with Jennifer McCrea, provides some advice on how to achieve that balance.

The world of philanthropic funds could also benefit from borrowing the concept of co-investment from PE funds. Co-investment is when PE fund investors have the opportunity to invest additional funds in a business, alongside and separate from those invested by the PE fund itself. This lets the investors increase their exposure to a deal without having to pay an additional share of the profits to the fund managers. Large donors in the philanthropic fund space could have the opportunity to co-fund particular nonprofit organizations—a win-win for everyone involved.

5. Information sharing versus competition. Unlike PE funds, which keep much of their information confidential, philanthropic funds often foster healthy information-sharing and cooperation among the organizations they support. They also often work on common problem-solving strategies with other kinds of donors. These include multilaterals such as the World Bank, the Global Fund, or the World Health Organization; bilaterals such as USAID and the UK’s Department for International Development (DFID); and large foundations, corporations, and significant individual donors. These cooperative, open, efforts are often very valuable and should be encouraged.

Sometimes, however, nonprofit groups devote their energy to competition, rather than cooperation and information-sharing. I’ve observed instances of duplication of services, arguments regarding which group should receive funding, and cases in which nonprofits try to do too much for competitive reasons rather than focusing on what they do best. Sometimes large nonprofits compete for funding via “contests” or “bakeoffs” designed to reveal which organization has the most exciting strategy to address a particular social problem. I’m not convinced this competitive approach yields better results or draws out greater capital investments than a more cooperative system.

6. Organization versus system focus. The PE industry is focused on investing in specific companies that can be improved, grown, and then sold or taken public for a profit. In the philanthropic fund industry, by contrast, the focus is—or should be—on sustainably improving a system to address a social problem. This often involves investing in ways that go beyond supporting specific organizations. For example, philanthropic funds working on the malaria challenge have not only invested in specific nonprofit organizations, but also supported efforts involving communications/media, policy change, coalition building, and data tracking. This is an important contribution philanthropic funds can make, which goes beyond the organization-level focus most individual donors have. It is also one of the ways philanthropic funds can and should pursue strategies that differ from those used by counterparts in the profit-driven world of PE.

Action Opportunities for the Near Future

For those in the philanthropic world who are interested in building on the successful practices of private equity, here are some fruitful areas for action in the years to come.

- Professionalize training of philanthropic fund teams. Just as the PE industry has created professional career paths from investment banking and industry to the PE field, the philanthropic fund industry should work with academic institutions to develop and embed cases and training programs that can serve to prepare professional managers of philanthropic funds. The field needs more system-focused leaders who can focus on sustainable problem-solving at large scales.

- Create simplified reporting and measurement systems. Simplification of accounting and reporting systems helped streamline deals between PE funds and their investors. Philanthropic funds should follow this example. Industry leaders should seek to retain experts from accounting firms and academia to help set standards and develop consistent reporting formats to replace the wide array of reporting donors require.

- Develop a common legal form. In the PE world, the creation of standard, general partner/limited partner structures and documents greatly streamlined and simplified the solicitation and closing of fund commitments. In the philanthropic space, donors should retain one or more leading law firms to work with a donor committee to standardize fund structures. This would make management of philanthropic funds easier and more efficient in the future.

- Encourage binding donor commitments. Imitating the form of commitment found in the PE world, philanthropic donors should commit funds for a specific period of up to five years. This would permit professional philanthropic teams to take a longer view on their objectives and how to achieve them, and would lead to enhanced performance over time. To create the donor trust and confidence needed for these longer-term commitments, management teams would need to show strong track records of achievement and expertice.

There’s a vast sea of funds from many of the world’s richest individuals and families available to support the philanthropic world. We have good reason to believe that a large number of those wealthy individuals are prepared to significantly increase the level of their giving, provided we can create an array of highly professional management teams to invest those philanthropic donations effectively. I believe today’s emerging philanthropic funds—focused on specific global challenges, committed to systems-level solutions, and dedicated to long-term, sustainable objectives—will be able to help attract greatly increased philanthropic flows of capital from high-net-worth families around the world, thereby putting solutions to some of humankind’s most intractable problems within reach.

Editor's note: March 25, 2019 | The number of diseases addressed, work locations, and committed funders of the Reaching the Last Mile Fund have been updated.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Jeffrey C. Walker.