Collaborators (data scientists, analysts, designers, and social sector leaders) "code switch" at a 2017 #GivingTuesday DataDive exploring giving behaviors and philanthropic trends—an event hosted by DataKind, 92Y, and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. (Photo by Aaron Adler)

Collaborators (data scientists, analysts, designers, and social sector leaders) "code switch" at a 2017 #GivingTuesday DataDive exploring giving behaviors and philanthropic trends—an event hosted by DataKind, 92Y, and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. (Photo by Aaron Adler)

We are at an inflection point in the social sector. The rise of digital technology has opened a chasm between mission-driven organizations who are able to harness the power of data and technology, and those who cannot. Despite the pace at which technology is changing daily life—as we see autonomous vehicles taking to the streets and Facebook algorithms challenging US democracy—few individuals employed in the social sector understand data governance, algorithm design, and other technical concepts, and their significant implications for mission-driven organizations.

First of all, let’s clarify what we mean when we talk about data in the social sector. The practice of measurement, learning, and evaluation, which aims to produce data about the effectiveness of a program’s intervention through surveys, reviews, and other types of targeted feedback, has been around for decades. But the trillions of bytes of digital data that pour out of cell phones, laptops, and satellites today, as well as transactional and administrative data, has exponentially expanded the potential. It has also given rise to wholly new capabilities such as automation with machine learning and artificial intelligence. These technologies consume data as an input to train algorithms which are powerful tools for optimizing efficiency, revealing patterns invisible to the human eye and brain, and power impact.

This digital data is what trains the algorithms that dictate your Facebook newsfeed and inform advertisers of whether they should target you with their products and services, but it can also be harnessed for good. It can have significant, even game-changing, implications for organizational effectiveness, revenue and expense models, and impact. For organizations like Medic Mobile, which designs and delivers software for health workers providing care in hard-to-reach communities, or GlobalGiving, the first global crowdfunding platform, these algorithms make it possible to achieve impact more efficiently and effectively. For example, Medic’s users collect an enormous amount of ground-level data each day using the app. This data can serve as a real-time feedback loop to improve care and increase efficiency for health workers as it is fed back into automated workflows. At GlobalGiving, a simple algorithm automates due diligence, flagging applications with problematic keywords. Instead of a human having to review hundreds of new applicants, they spend their time only on potentially problematic ones.

A dearth of digital fluency

Are you enjoying this article? Read more like this, plus SSIR's full archive of content, when you subscribe.

But while these organizations—essentially nonprofit tech companies—exemplify innovation in the nonprofit sector, they are by and large the exception. Whereas GlobalGiving and Medic Mobile have been digital since their inception (2002 and 2010, respectively), most nonprofits struggle to allocate resources to data and technology capacities. The net result is that the vast majority of the sector lacks the basic data fluency it needs to thrive in the 21st century. This includes not only the expertise to understand complex data sets, but also the ability to interpret and translate that information to others in accessible terms.

This lack of fluency comes at a time when government is shrinking; the private sector is growing; and global challenges like climate change, famine, and refugee crises are worsening. All of this means the demands on mission-driven organizations, which exist to address challenges at the core of inequality and injustice in our world, are increasing.

To keep pace, it’s crucial that mission-driven organizations foster data fluency so that they can execute the kind of innovative, entrepreneurial, transformational programs and collaborations necessary to remain effective, vibrant, and sustainable. Data expertise remains the province mainly of specialists, and those specialists are not always the best at translating what they know into accessible terms. The problem is that a basic functioning knowledge of analytical practices is necessary for social impact strategy, and it’s unsustainable for it to remain something that very few know how to navigate.

The art of “code switching”

Mari Kuraishi, co-founder and president of GlobalGiving, knows this well. Having founded a digital-first organization in 2002, she runs the entire organization on data-driven decision-making. “Every channel owner [akin to a department head] has access to granular data and runs the business on the basis of those numbers. We hold people to aggressive targets that force them to pay attention to the dynamics within their channel, to ensure that the toplines are matching up to what we ask them to do,” she says. “Everyone at GlobalGiving, to varying degrees, can translate technical concepts to non-technical contexts.”

This capacity struck Kuraishi as a new form of “code switching.” The term is rooted in the idea of an experience where, she explains, “you might speak Spanish at home, interacting with your relatives and eating Latin food. You then go to school, you speak English, you might not bring your home food to school, because it doesn’t fit the prevailing paradigm. The translation is internalized, but it takes the idea of different prevailing norms and measures that need to be translated back and forth.”

The “code switchers” in the social sector are people who fill an important delta between specialists—data scientists, machine learning experts, and AI designers—and people who need to rapidly learn and implement those learnings in their own work.

The role of code switchers

Right now, the state of data in the sector is poor; it’s siloed, often poorly mined and analyzed, with findings often sitting unused in unread white papers. Collaboration around data is also poor; other industries, particularly in the private sector, are miles ahead of the social sector in pooling their data and using the results for the benefit of all. It simply makes smart business sense to use collective data to understand the landscape of the marketplace and determine shifts and trends in customer behavior.

In addition to making business sense, there is also a social good case for leveraging data and technology—and doing so collaboratively. We should be leading the way in using data for industry benefit, and instead, we’re struggling just to catch up. If we are to make real progress, we need to understand what data we have and how we can work with others to maximize its effectiveness, and then translate it so all players understand what the problems are and how data can help solve them. Code switchers are central to this evolution, and eventually everyone in the social sector will need to acquire their skills.

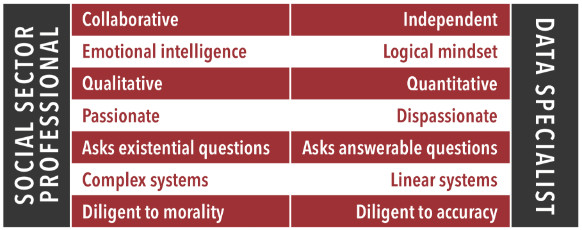

To understand the need for code switchers, we need to look at why the delta between data experts and the social sector exists in the first place. These are obviously generalizations, but the following table describes characteristics that might either represent or be associated with each type of role/person/skill-orientation:

Problems can arise when these two worlds aren’t properly bridged. Too often, the information (the data, not useful in and of itself) exists on one side, and the people who want to use evidence to make change and drive impact are on the other. The key is identifying the problems that need solving and which questions are answerable.

“When people aren’t data-savvy, they just envision a wall of information that isn’t useful to them,” says Gabriel Rhoads, senior evidence director at Project Evident, which works with nonprofits on evidence-based program development. “The hurdles that can make it useful are cumbersome, intimidating, and off-putting. The data scientist does the analysis, but the translator helps with the ‘to what end.’”

Those translators—or code switchers (who, to be clear, can come from either social sector or technical backgrounds)—are both:

- Wonky and public facing. Code switchers are concerned with the what and the why, and able to contextualize information in a powerful and useful way.

- Analytical and empathetic. Code switchers are concerned more with whether they are presenting an analysis of complex information in relatable human terms rather than “smart” sounding jargon.

- Smart, warm, and approachable. Code switchers have a capacity to present technical concepts accessibly and in human terms.

“There’s a role for people who help guide decision-making based upon analysis,” says Rhoads, noting that he often thinks of himself as the fictional detective Colombo, simply asking questions to get each side to put it all on the table. “The real guts of that is helping to understand: What critical questions do you have? What are you trying to answer? Some data scientists might be good at that, some might not be. The ‘translator’ is the person who might not be intimidated by the data itself and will be able to get to the critical questions. A good translator prevents the missing of the boats.”

The most-effective 21st-century social sectors leaders will not only embody the characteristics of code switchers, but also look for these translators throughout their organizations. Data-fluent development directors should be able to report on the velocity of the revenue pipeline just as well as telling an impact story that will move a donor to support the organization. Likewise, a code switching-capable data analyst or director of finance can convey important information in actionable, human terms.

Social sector organizations would do well to be on the lookout for these qualities and to consider code-switching qualities highly valuable in any role, junior or senior. Funders also need to value this capacity and make more resources available to develop data fluency across the social sector.

Finding useful information in patterns unseeable to the human eye; making better, more accurate decisions; and preventing the “missing of the boats” are all good reasons to leverage data and technology more effectively. Perhaps an even more compelling reason is the impact that automation and predictive technology can have on an organization’s bottom line. As Kuraishi puts it, “One of the reasons why we’re constantly looking at what can we do with better data and algorithms is because, as we handle more donations and more nonprofits, we want to do so without adding staff at the same rate. The financial driver for us is pretty important.”

The world has fundamentally changed, and data and technology will continue to accelerate the pace of transformation. If social sector organizations are to drive meaningful change at scale to address the numerous challenges facing society, we need to invest in code switchers across every vertical of our organizations.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Julia Rhodes Davis & Asha Curran.