(Photo by iStock/stefanschurr)

(Photo by iStock/stefanschurr)

Global crises of the past two years have yielded at least one silver lining for nonprofits: They have accelerated a movement among grantmakers to match the duration and flexibility of their funding to the arc and demands of change. Such a shift couldn’t come at a more important time for organizations addressing acute threats to climate, health, our social fabric, and world democracy.

Indeed, in a Ford Foundation-commissioned study by MilwayPLUS of leaders of funders and nonprofits that had experienced this shift, we found crises like the COVID-19 pandemic to be one of five key accelerators propelling grantmakers to cover the full costs of achieving mission, in ways that share power with grantees, vest trust, and spur greater impact. Said Larry Kramer, president of the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation: “COVID was an accelerator in that it forced funders for different reasons to release control, and then they discovered, ‘Oh, it worked just fine...even better.’”

Advocacy for this shift has come in many forms, including The Bridgespan Group’s Pay-What-It-Takes, Philanthropy California’s Full-Cost Project, the Trust-Based Philanthropy Project, and the Ford Foundation’s BUILD initiative. Ultimately, it’s all been a call to more equitable grantmaking. While multi-year, flexible funding is not the entirety of what makes grantmaking more equitable, it is a key entry point for funders seeking to share power with grantees. And it’s something nonprofits have requested for years, with few results.

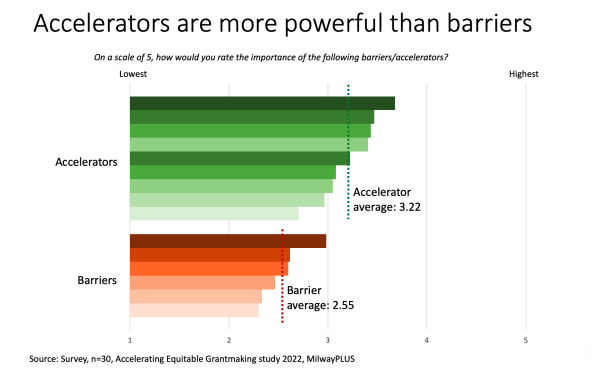

The top accelerators of change that surfaced in interviews, an in-depth survey, and four focus group discussions with chief executives at nonprofits and funders were the following:

- Getting clear on values

- Listening to feedback from grantees

- Adopting an equity lens on grantmaking

- Responding to group or peer influence

- Reacting to global and political crises

Are you enjoying this article? Read more like this, plus SSIR's full archive of content, when you subscribe.

This five-cylinder engine has propelled funders to break through historic barriers to change like funder budget policies, trustee bias for control, and bureaucratic foundation roles and systems, all of which imbalance power in the grantor-grantee partnership.

We will examine each accelerator, ways that leaders can harness them, and their overall implications for redefining foundation roles. Importantly, the findings calibrate the observations of grant providers with the experience of organizations doing the work.

Five Accelerators

We began our research by asking funders and nonprofits what stood in the way of more equitable grantmaking. They cited funder budget policies as the number one barrier, locking grantees into fixed overhead rates or one-year grant cycles. Number two, relatedly, was funders’ bias for control and fear of risk-taking. These are important and bear continued attention.

But we were pleasantly surprised to see that across the board, both funder and nonprofit leaders said accelerators of change toward multi-year flexible funding far outpace the drag from existing barriers.

Click chart to enlarge

Click chart to enlarge

Indeed, the top two barriers (budget cycles, trustee bias for control) lowered when boards embraced what our study found to be the number one accelerator: Boards “getting clear on values” and how those connect to strategies for achieving change. Three other key barriers—grantmaker-grantee power imbalance, funder beliefs about accountability, and funders’ bureaucratic approaches—were similarly eroded by positive forces for change.

1. Getting Clear on Values

Funders that zeroed in on their values and goals found a natural path to changing grant practices. They sought to fund the years it would take to roll out a model or influence a behavioral norm, and they gave grantees leeway to apply funds when and where most needed to advance the cause.

“We needed to do values work,” said Lauren Scott, executive director of the Harris and Eliza Kempner Fund, a place-based funder in Galveston, Texas, “and affirmed that equity, grassroots inclusiveness and responsiveness were part of our values.” The exercise led Kempner to unrestrict grants and streamline reporting, in line with elements of a Council on Foundations-hosted COVID pledge—which prompted their introspection.

Ways that funders clarified their values included:

- Embarking on a values discussion across board and staff, by establishing a working group or inviting a third party, such as Trust-Based Philanthropy Project, to facilitate the exercise.

- Discussing how to express values through grantmaking practice, brainstorming specific changes such as more flexible grants and fewer application and reporting requirements.

- Asking for feedback from grantees on how funder values come across, as part of an ongoing dialogue that invites grantees to suggest process improvements.

Take, for example, The California Endowment. Charged to “ensure the availability of and access to affordable health care and related services to the people of State of California,” it made multimillion-dollar grants to clinical services and infrastructure in its early years. But a values exercise led the board to conclude that health happens not in a doctor’s office, but in homes, schools, and communities. The foundation refocused on neighborhood environments that support health and invested $1 billion over 10 years in 14 neighborhoods of Los Angeles most devastated by health inequities through an initiative called “Building Healthy Communities (BHC).” A 10-year review of BHC, found it had scored 1,200 distinct policy and system changes as a result of growing the ecosystem for prevention, by teaching health and well-being in schools, advocating healthier land-use decisions, and growing the voice of historically-excluded adults and youth to engage in public policy. Said Dr. Robert K. Ross, foundation president, “We’ve been so impressed with the outcomes. The smartest thing we did was to agree [the funding] should be for 10 years.”

Or consider the Overdeck Family Foundation, based in New York City, with a focus on education. After five years and more than 300 grants across research, policy, and direct service organizations, founders John and Laura Overdeck and their vice president, Anu Malipatil, took stock. They identified home-run grants demonstrating vision, legacy, and impact, and gathered feedback from grantees via a grantee perception report (GPR). They asked their team to weigh in on which grant outcomes felt closest to their mission and values. “The truth was that all three stakeholders, trustees, staff, and grantees, were not feeling super thrilled,” said Malipatil. “The donors were mainly excited about evidence-building and direct service investments in early- and growth-stage organizations. The GPR showed grantees weren’t clear on Overdeck’s strategy and found interactions somewhat transactional. And the team felt they spent too much time on process and reports versus grantee relationships.” After much discussion, Malipatil proposed a venture-inspired model for the foundation’s next chapter focused on multiyear, unrestricted grants for early- and growth-stage nonprofits, reimagining grantee relationships as transformational in achieving better education outcomes.

2. Grantee Feedback and Initiative

Funders credited grantee feedback and initiative as the second most powerful motivator for multi-year flexible funding, something our survey showed nonprofits leaders didn’t echo, rating funder peer influence more highly. But foundation presidents and CEOs told us that candor from grantees on what it took to achieve impact—flexibility to apply funding to core support where needed, and for the length of time required to change laws or reduce inequality—gave staff a case to make to their board.

Some ways funders leaned in to grantee feedback included:

- Making grantee feedback a part of every board meeting and board-staff retreat, whether via survey data, grantee speakers, or program officer presentations.

- Asking grantees about their long-term visions and plans, and where they aren’t codified, supporting their creation.

- Moving beyond feedback to consultation by asking grantees to contribute to strategy development, advisory committees, board roles, and/or participatory grantmaking, where grantees shape docket decisions.

Oak Foundation, based in Geneva, Switzerland, received input that pivoted much of its grantmaking to core funding. In 2016 it invited nonprofit thought leader Vu Le to address an in-person event with staff and trustees. “We all had a moment of truth,” recalled Program Officer Medina Haeri, “Vu Le used the analogy of baking a cake—if you want a fully baked cake, you can’t only pay for the ingredients. You also have to pay for electricity, the bake staff, and all the other costs beyond ingredients. That was a light bulb moment.” Before the event, Oak had a hard and fast rule of funding only 15 percent overhead. But Le’s wake-up call led Oak’s leadership to conclude that 15 percent was an arbitrary number and to de-emphasize project funding. Added Senior Advisor Adriana Craciun, “We work in service of our partners, and that leads to multi-year, general operating support.”

President Doug Griffiths, who arrived at Oak three years later, found the foundation pretty far along the multi-year, flexible funding journey, and now makes a habit of asking program officers to defend any grantmaking that veers from it. He notes sensible exceptions for short-term research, or to earmark a specific school within a university, or to comply with IRS expenditure responsibility rules in grants to non-US 501(c)3’s. What’s key, he says, is that the default becomes core support for at least three years, which he invites grantees to reinforce. “I encourage our grantee partners at board meetings to talk about the difference between core funding and other funding streams, and what it means.”

Nonprofits shouldn’t wait for foundation invitations, though. As a grantee, Sixto Cancel, CEO of DC-based Think of Us, which uses technology and participant feedback to influence foster care policies and deliver services, found he needed to take initiative to build trust among his funders. Some knew the nonprofit for its app, others for advocacy, and still others for direct-service resource navigation to support foster youth and kinship parents. “They didn’t realize how our programs fit together,” said Cancel. Now, every three months, Cancel invites his funders to a detailed update on one program and how it ties to everything else the nonprofit does. He underscores where the government has picked up funding to grow services. “Communication is key,” says Cancel. “Every seven-figure gift has been from people with a [clear] understanding of tech and how it connects to scale.”

3. Grantmaker’s Equity Lens

Racial reckoning in the wake of George Floyd’s murder led US funders to respond to documented racial bias in philanthropy, echoed by a global movement to support historically marginalized groups. Foundations created funds to support Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC)-led nonprofits; philanthropists like MacKenzie Scott and Jack Dorsey embraced no-strings-attached, multiyear grants to advance racial equity. While Philanthropic Initiative for Racial Equity rightly cautions not over-estimating the scale of this shift, a growing number of funders and nonprofits explicitly name flexible grantmaking as a strategy for advancing racial equity. Cheryl Dorsey, CEO of Echoing Green, which supports early-stage social entrepreneurs, found a Scott grant transformational. “MacKenzie Scott’s unrestricted grant was a game changer,” said Dorsey, who used the catalytic gift to launch a $75 million Racial Equity Philanthropic Fund.

Equity-committed funders are:

- Gathering the data on diversity of leadership among their grantees, then setting and pursuing goals to grow investments in BIPOC leaders that align with their theory of change.

- Uprooting onerous proposal and reporting requirements. The historic gap in multi-year, flexible funding for BIPOC leaders has created an administrative burden, robbing program delivery time and impact.

- Appointing board members and hiring program officers with lived experience of the equity issues the funder seeks to address, to identify and connect with a broader set of nonprofit leaders.

Both institutional and family foundations established racial equity funds and took hard looks at their own staff diversity and that of their grantees. Seattle’s Satterberg Foundation expanded its geographic focus from states with family connections to support Black Lives Matter nationally, and increased its endowment payout to create a 10-year, $50 million fund to help resource the efforts of Black and Indigenous-led community organizing. “In 2021 the Reparative Action Fund granted $10 million in general operating support to 59 organizers across the country,” said Executive Director Sarah Walczyk.

For a spectrum of funders, an equity lens is sharpening their focus on historically marginalized groups including women and girls, LGBTQ+, stigmatized castes, and people with disabilities, all calling for flexible, long-term funding to catch up after years of neglect. The Peter and Elizabeth Tower Foundation of Buffalo, New York, for example, formed an advisory committee of young people with intellectual disabilities to inform the board room. “We learned so much working with them,” said Tracy Sawicki, Tower’s executive director. “We changed how we presented our grant applications. We made videos, we worked with staff who knew and engaged them in a process that exceeded everyone’s expectations.” Fast forward to 2021 and Sawicki told us that Tower was working to appoint advisory members to the board and addressing grantmaker-grantee power sharing by giving money to the advisory group to grant out.

4. Group/Peer Influence

Nonprofits we surveyed rated peer influence among funders as the top accelerator of more equitable grantmaking, while funders rated it lower. Nonetheless, Stephen Heintz, president of Rockefeller Brothers Fund, told us, “Peer influence should not be underestimated. You find the peer groups that you're comfortable in, and those are the ones you really rely on. And you should make sure to find the peer groups that you're not always so comfortable in, because they're the ones that are going to challenge you to really examine your own behaviors and practices and biases and assumptions.” In philanthropy, peer influence can take many forms, such as joining pledges or other public commitments; joining funder collaboratives; or signing op-eds or public statements.

At a minimum, public commitments bring organizations already adhering to recommended approaches into the light. At best they attract converts. Funders harnessing peer or group influence to accelerate reforms are:

- Taking The COVID-19 Pledge to publicly commit to equitable funding practices.

- Joining funder collaboratives committed to equitable funding practices, which gives participants experience with practices like flexible grantmaking that may not be the norm in their foundations.

- Sharing and amplifying research from nonprofits and philanthropy to make the case to staff and board for multi-year, flexible funding, including as a way to lift payouts without growing staff.

A good example of putting peer influence in the service of growing equitable grantmaking is The Grassroots Resilience Ownership and Wellness (GROW) Fund, initiated by Mumbai-based EdelGive Foundation. GROW was designed as a collective of philanthropists and includes Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Manan Trust, Rohini Nilekani Philanthropies, A.T.E Chandra Foundation, Ashish Kacholia, and the Edelweiss Group. They are focused on growing and sustaining 100 small and mid-size social impact organizations across India for a two-year period, by supporting their core costs and capacity building in finance, human resources, and technology. In other words, regardless of co-investors’ grantmaking norms, the collective’s grants go to core support. “We have to make a tribe of best practice funders,” said Naghma Mulla, executive director of Edelgive. “So groups come together and say, ‘This is our new normal,’ which attracts more groups.”

Observed Nicky McIntyre, CEO of Foundation for a Just Society, which often supports participatory forms of grantmaking: “Funders should come to participatory funds prepared to learn and engage. Don't expect to turn up and give a small, very targeted, restricted one-year grant because that group will want to talk you out of that.“ McIntyre notes that some funders make their first very flexible grants via collaborative funds because restrictions are not an option. “They've got cover,” said McIntyre. Or, in a similar vein, they make grants to community funds or public foundations that regrant flexible, multi-year funds to community groups.

Matt Forti, managing director of food security NGO One Acre Fund, credits collective giving initiatives like The Audacious Project and Co-Impact with being the nonprofits’ most equitable grant partners since these funders have “pre-organized for, in most cases, 5-year investments, funding things like systems change, policy and movement building.”

5. Global & Political Crises

More than 60 percent of funders, according to a December 2021 report by the Center for Effective Philanthropy, unfettered their funding during COVID. In addition, three quarters reduced reporting requirements to allow grantees to direct funds where most needed and ease paperwork. A full two-thirds of funders that shifted gears said they intend to stick with their new practices. In our focus groups, funders that had been discussing reforms pre-crisis, said the crisis galvanized action. These funders gave more and more flexibly, although not necessarily longer term, given changing conditions.

Likewise, political threats to a field, like immigrant or LGBTQ+ rights, or to democracy itself, create an urgent impetus for change. Nonprofit leaders can seize such moments to make core funding needs known. “When the state denied our HIV/AIDS program, it woke up other funders,” said LaSaia Wade, ED of transgender support nonprofit Brave Space Alliance in Chicago.

Funders using crises to galvanize reform are:

- Tapping into community voice and grantee expertise to grasp crisis implications and what matters quickly, identifying service shortfalls, populations most at risk, and where to advocate.

- Seizing the opportunity to reform grantmaking by converting long-simmering discussions of more equitable grantmaking to funding norms, embracing simplicity, and shifting reporting burdens (e.g., video check-ins; multi-funder proposals, and reports).

- Starting the conversation on revitalizing values and focus. Crises underscore the need to refresh board thinking, especially as markets bolster endowments and there’s more money to give.

In South Africa, Audrey Elster, executive director of the Raith Foundation, which funds national movements, found that COVID gave long-simmering board conversations about expanding core funding the impetus they needed to create a new norm. Said Elster. “As a staff, I think it’s incumbent upon us to be alert to crises and opportunities and take advantage of those moments.”

To advance multi-year grantmaking, the Hewlett Foundation developed an approach, out of crisis, that foundations with strong endowment growth could use. Said Hewlett’s Kramer, “During the 2009 recession, many programs cut their budget by shortening three-year grants to one-year, even though these were grantees we intended to continue supporting. That was bad for them and for us, as it was a lot of extra make-work.” As the endowment grew back, Kramer and his team figured out a way to preserve and use a chunk of unallocated funds on a one-time basis to extend grants back to three years, by extending grants of 1/3 of the cohort each year. “After the third year, all the grantees were on three-year grants,” said Kramer, “But the budget needed was the same as in year one, and the grantees were staggered in terms of renewal.”

New Roles and Systems for Funders

These five accelerators of equitable grantmaking offer fodder for board-room discussions, staff retreats, and grantee gatherings. Such conversations should include a hard look at how roles and systems at the funder itself should shift to support new norms. After all, vesting more trust in grantees as experts and lengthening grant cycles will de facto slim annual dockets and incentivize systems that value conversations and insights across years. They could also inspire boards to create multi-year foundation budgets to facilitate multi-year grant cycles.

John Taylor, president of Wellspring Philanthropic Fund, has cultivated a culture among program officers of long-term grantee relationships, saying, “That sets the table for the kind of trust that we need.” Wellspring’s budget policy reinforces this aim. For example, a program with a current annual grantmaking budget of $10 million can grant up to $7 million of the following year’s budget and $4 million of the third year’s to create multi-year portfolios. “In practice, our programs use this latitude to award a mix of one, two, and three-year grants.” The leeway has created a culture of multi-year funding where program officers have time to think about non-monetary ways to help grantees, including innovations like teeing up a new award as an amendment on an existing grant to lighten the paperwork.

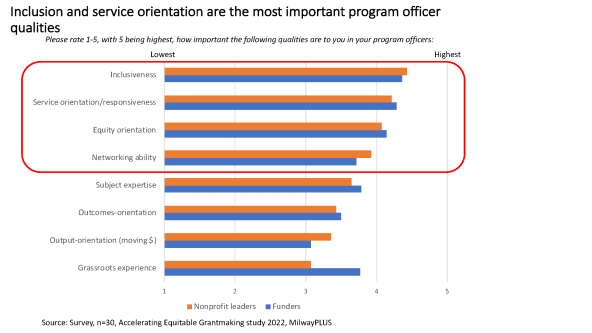

In our survey, funder and nonprofit leaders agreed that the hiring criteria for program officers today should prioritize inclusiveness—a responsive, service orientation; a focus on the flow of grants to underserved communities and their leaders; and networking ability to help grantees grow their ecosystem of collaborators. This dovetails with a finding from the Center for Effective Philanthropy: The quality of grantees’ relationship with program officers is the best predictor of a grantee recommending that funder to others.

Click chart to enlarge

Click chart to enlarge

At the Ford Foundation, equitable grantmaking has included developing a program, BUILD, that two of our co-authors (Reich, Cardona) guide. It provides grantees five years of general support, combined with more targeted but still flexible organizational-strengthening support. In part because of BUILD, more than 80 percent of the foundation’s overall funding is now general or core support.

Nancy Rauch Douzinas, president of Rauch Foundation of Long Island focuses her time on helping grantees network. In particular, she builds grantees’ clout in civic debate via creating cross-sector partnerships. “When I think about balancing power between grantmakers and grantees, I think about how the nonprofit sector needs allies in other sectors, across business, labor, and community,” Douzinas added. “Place-based foundations have the power and the capacity to play a kind of agent's role in making that happen.”

Such funder accompaniment on the journey to social impact sits well with Mary Marx, CEO of Pace Center for Girls, a girls empowerment nonprofit based in Jacksonville, Florida. “The learning community that a funder has access to is really critical.”

Conclusion

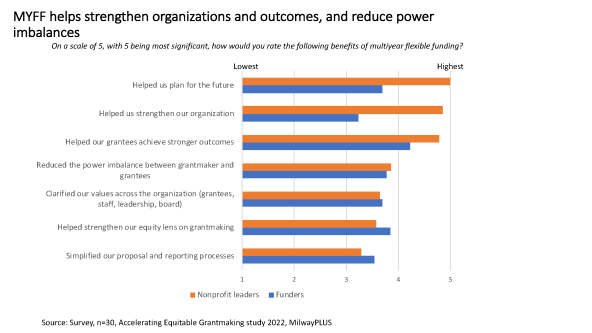

In our research, nonprofit leaders were virtually unanimous in saying that multi-year flexible funding enabled them to maximize their impact. And funders who embraced the five accelerants of change came to see that as well.

Click chart to enlarge

Click chart to enlarge

Said Kris Hayashi, executive director of the Transgender Law Center in Oakland, California, “[MacKenzie Scott’s grant] allowed us to do so much and gave us sustainability. We planned out the next three-to-four years.” Added Monisha Kapila, co-CEO of leadership advisor ProInspire, another Scott grantee: “The biggest benefit of multi-year, flexible funding has been the ability to hire and grow our capacity so we can grow our work.” It’s exactly what funders in our study said they had learned: Only strong organizations could deliver strong outcomes. “Our ethos has been we have to build good organizations, not just fund good programs,” said Vidya Shah, executive chair of Edelgive. “It’s kept us funding non-program costs.”

After decades of advocacy encouraging funders to adopt more flexible, long-term practices, the crises of 2020 appear to have created real momentum toward this happening at scale and validated the approach as a key component of equitable grantmaking. Funders who have embraced these changes and are thinking of how to sustain them or what comes next, and those who have considered them but not yet taken the plunge, can use the five accelerators, drawn from the experience of funders and nonprofits, to keep the momentum going. “The markets have been kind to philanthropy… This should be the moment to translate that into multi-year funding,” Ross of The California Endowment told us. “Three years and up ought to be the target. Five years is ideal.”

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Katie Smith Milway, Amy Markham, Chris Cardona & Kathy Reich.