I have had a front-row view of the boom under way in social entrepreneurship. As a social entrepreneur myself and a lecturer in the Program on Social Entrepreneurship at Stanford University, I have watched the launch of so many exciting innovations for good. And yet, while for many nonprofits this has been an invigorating and transformative time, so many other nonprofits have struggled on the sidelines. Despite doing important work, many operate in constant survival mode, scrambling for the money to make payroll every month. In 2014, almost two-thirds of reporting public charities in the United States had an annual budget of less than $500,000.

For the past five years, I have been traveling around the country, visiting the founders, leadership teams, and funders of dozens of what I call breakthrough social startups. I’ve interviewed over a hundred social entrepreneurs, academics, and philanthropists, both newcomers and veterans in the field, including the leaders of Teach for America, City Year, DonorsChoose, and charity: water, and started our conversations with a simple question: “What is the key to nonprofit success?” Social Startup Success highlights the findings of my study in the form of a playbook for any organization that wants to increase its impact.

In these uncertain times, when so many social problems are not only persisting, but in many cases, worsening, we need every bit of creativity and determination to find better solutions. My hope is that this book and the tools it recommends will help you to make your own organization, or those you are supporting, thrive. We need to spend less energy keeping organizations alive, so that we can devote more energy to spreading positive impact. This book is a guide for how to do that. —Kathleen Kelly Janus

Attracting funding is by far the biggest barrier to scale. In fact, 81 percent of the social entrepreneurs I surveyed identified access to capital as their most pressing problem. Nonprofits at all levels struggle to get noticed by new funders. What separates the best organizations is a culture of testing a variety of funding streams to figure out what works. By purposefully experimenting with revenue, they discover a funding model both authentic to their mission and effective at raising money.

Earned income such as selling products or services is fertile ground for experimentation. My survey revealed that successfully developing an earned-income strategy was one of the ways organizations broke through the $2 million annual revenue barrier. The responses showed that while organizations typically start out with mostly philanthropic support, with just 8 percent of their budget coming from earned income, as they grow past $2 million in revenue, they are more likely to report that a higher percentage of their budget is covered by earnings; on average about 30 percent. These findings indicate that testing earned-income strategies should be a key ingredient of efforts to scale. But my research into how nonprofits generated earned income also highlighted that the process is fraught with challenges, and is more viable in some subsectors, such as education and health care, than others.

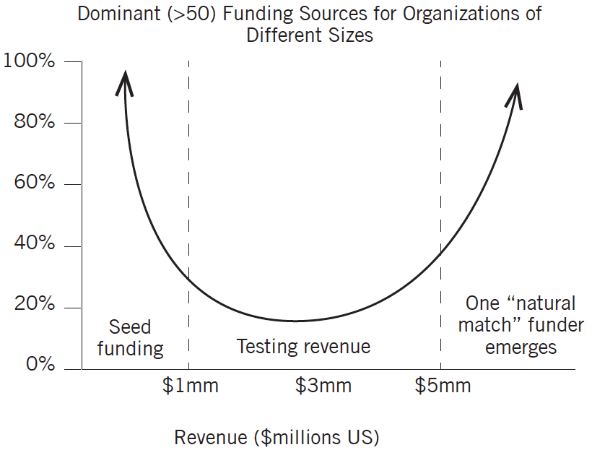

Dominant (>50%) funding sources for organizations of different sizes. Source: Adapted from William Foster, Ben Dixon, and Matthew Hochstetler, In Search of Sustainable Funding: Is Diversity of Sources Really the Answer?

The vast majority of organizations under $3 million in annual revenue will rely on a combination of funding sources to come up with a model that fits their unique mission and values. In one of the most widely read Stanford Social Innovation Review articles, titled “Ten Nonprofit Funding Models,” William Foster and his Bridgespan colleagues reveal that of the 144 nonprofit organizations created since 1970 that have grown to $50 million a year or more in size, each grew by more narrowly pursuing sources of funding, typically concentrating on one particular source: what they call the “natural match.” For example, the Sierra Club relies on membership fees.

A key point to highlight, however, is that their research also shows that organizations typically do not begin to transition to dominant funding sources until around $3 million in annual revenue. This underscores the point that while organizations that want to scale substantially should be driving toward finding one or two primary sources of reliable ongoing revenue, they should get there by testing a good diversity of approaches as they’re growing.

Many of the organizational leaders I interviewed remember the great recession of 2008 like it was yesterday. Virtually overnight, foundations that had promised multiyear grants reneged on their funding because their endowments had tanked along with the Dow Jones. Earned income was critical to many of them in order to stay afloat. Beyond providing a financial cushion, earned income helps bridge the gap lying before so many organizations: the funding they’re able to raise versus the amount they need in order to invest adequately in growth. Another benefit is that demonstrating your capacity to generate reliable income appeals to funders, many of whom have come to see earned revenue as a vital part of the “path to sustainability.” But before an organization begins playing with potential earned-income streams, it must establish the right expectations.

Take the case of successful Hot Bread Kitchen, a training facility for low-income women who want careers in the food industry, founded by Jessamyn Rodriguez. She smartly played to her strengths in conceiving the organization, after having worked for a decade in international development before she came up with the concept. A passionate foodie, she landed an internship in renowned chef Daniel Boulud’s kitchen. That happened by serendipity. She was interviewing for a job at a microfinance organization called Women’s World Banking, when a friend misheard her as saying Women’s World Baking. The idea of an international women’s baking collective struck her, and it is now located in the heart of Harlem in La Marqueta, a historic produce market dating back to 1936, which had fallen into decline until the organization redeveloped it. The space is divided into three separate areas of operation: a kitchen that hosts a six-month job-training program for low-income women, an area where they bake bread products for sale and an incubator where small-business owners in the food industry can rent space to make products they sell throughout the city, from grocery stores to markets.

Rodriguez told me the key reason the business has been successful is that they don’t sacrifice quality despite the fact they are mission driven, and after tasting their multigrain pepita bread I can attest to that. In fact, the organization sells its bread to a number of major retail outlets, such as Whole Foods and JetBlue, as well as some of the top restaurants in New York City. But even with a top-quality product and a strong personal network for building the market, she initially overestimated the extent to which profits from bread sales would support the organization. While at first she envisioned a model where her bread sales and cafe operations would cover close to 100 percent of her operating expenses, she realized quickly that goal would be hard to accomplish. She had underestimated the costs of the training, and overestimated the profit margins on selling bread. She was forced to reset her expectations, and had to go back to her donors with a new model that would continue to rely on philanthropic donations to support 35 percent of the program budget. Rodriguez told me that “in talking with our donors, I realized that people were attached to our strong outcomes and that was most important, not being 100 percent sustainable. Over time, my understanding of the economics of the business have changed a lot,” she told me, “and I realized that there is actually a huge benefit that comes from philanthropic funding that allows us to do more for the women we serve, such as providing child care during the classes.”

Foundations and donors, and organizational leaders themselves, must not put organizations under unrealistic pressure to fund more and more of their operations by selling products and services. Recall that in my survey, most of the organizations that had scaled to over $2 million in annual revenue reported that earned income accounted for 30 percent, which therefore is a reasonable target for many organizations to shoot for during the initial phase of growth. The bottom line: plan on grants and donations to almost entirely sustain your efforts for at least the first couple of years, as you experiment with building your revenue stream. If you decide you want to experiment with earned income, you should undertake a rigorous strategic analysis and a pilot program. Here is a five-step process for developing a viable earned-income strategy I highly recommend:

Step 1. Reaffirm your organization’s mission. Earned-income strategies work best for nonprofits when they are highly aligned with their mission. To assure that ideas are serving the mission well, you should perform an assessment of how clear your mission is by asking five or so people (a mix of staff and other stakeholders such as a board member and a funder) to describe the mission, without referring to your website or materials describing it. You could do this with a simple email request or perhaps by calling them. The responses will tell you whether or not you should spend some time aligning everyone on the objectives of the organization. Going through a theory of change is another way to ensure you have clearly articulated your organization’s goals.

Step 2. Brainstorm your options. Bring together your full team (staff, board and even external stakeholders) to brainstorm a variety of potential sources of income, and whittle them down to just a few to evaluate further. Think about the various categories of revenue. Can you charge your beneficiaries for services you already provide? Is there an invested third party such as a company or a government entity that might be willing to pay for those services? Does it make sense to launch a new business venture? What other types of revenue relationships can you form in your network?

Step 3. Assess total mission impact. Evaluate whether the proposed activities are likely to enhance or detract from the pursuit of your goals, and assess the potential net financial gain (or loss) of each idea.

Step 4. Evaluate feasibility. Analyze the internal capacity of your organization to conduct the required activities, considering whether you have the human resources and necessary experience, the financial stability and the appetite for the risk involved, as well as the likely demand for your products or services. Then assess likely funder support, which might involve making some calls to trusted funder advisors.

Step 5. Develop an action plan. Develop a design for a pilot program, following the steps for testing outlined in human-centered design. Solicit feedback about the design from professionals with experience in nonprofit earned-income programs as part of your testing process, perhaps by working with a paid or pro bono consultant, and also be sure to seek the advice of an attorney to assure you fully understand the tax implications.