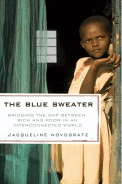

The Blue Sweater: Bridging the Gap Between Rich and Poor in an Interconnected World

Jacqueline Novogratz

272 pages, Rodale Press, 2009

If you don’t know where you’re going, any road will take you there, the Cheshire Cat tells Alice when she asks for directions in Wonderland. But what if Alice had known exactly where she wanted to end up, and just didn’t know which road would get her there? That is the challenge that entrepreneurs with a social mission face every day.

In her autobiography, The Blue Sweater, Acumen Fund founder and CEO Jacqueline Novogratz engagingly captures one such mission in need of the right road. In her case, she hopes to use the power of markets to achieve social transformation, primarily through providing economic opportunity to the poor and marginalized. Through the course of the book she proves herself one of the increasing number of “ordinary” people who accomplish the extraordinary through sheer courage, fortitude, resilience, and the pursuit of a mission much larger than any one person could ever accomplish in a lifetime. And her story might also provide the missing piece for those struggling to change the world: her great willingness to listen to, and learn from, all those she comes across during her journey.

Novogratz’s journey begins as a new college graduate, when she joins Chase Manhattan Bank and flies around the world to review the bank’s loans. She loves banking, but as it turns out, she loves the idea of lending to the poor even more, and Chase is not about to do that—this is the 1980s, after all. So despite the personal validation, prestige, and security offered by such an institution, she resigns to accept a position at a nonprofit that uses the platform of the African Development Bank (ADB) to foster local organizations that promote economic development in West Africa.

With no ability to speak French or knowledge of the region, and a huge dose of naïveté, she lands in Africa—first in Kenya, then on trips throughout the region. We follow her as she is rejected by the African women leaders who disapprove of having a young American woman in a central position at the ADB, when it should have been one of them. We accompany her to Rwanda, where she works alongside Rwandan women leaders to set up a microfinance organization and struggles to get borrowers to take their responsibilities to repay seriously.

It is this section of the book that probably most endears us to the author. There is her downright funny depiction of her “too American” attempts to convert shy Rwandan women into forward, aggressive sales agents at a local bakery where she was consulting. And she clearly shows us how she herself was transformed by the process of seeking to transform others, despite her admission that “we were getting our feet wet and didn’t know exactly what we were doing.” (How many times have we ever felt that way?) She comes to understand that economic development and social change cannot be imposed from without. They must be sought and grasped by the individual pursuing opportunities for self-realization.

After her two-year sojourn in Africa, Novogratz returns to the United States for a stint with the World Bank in Washington, D.C., ending up back in Africa, this time Gambia. And here begins a tragic subplot, the massive waste of financial and human resources channeled by well meaning development agencies. Novogratz’s experiences show, governments too often derail the money intended to help the poor so that it ends up padding civil servants’ pockets instead. This part of the book is not a surprise, unfortunately. That’s because we have heard of—and many of us have witnessed—the outrageous corruption that occurs in the name of development.

The most gripping part of Novogratz’s story comes next—after she has gotten her MBA from the Stanford Graduate School of Business and made her first official foray into philanthropy as a Rockefeller Foundation Warren Weaver fellow. She returns to Rwanda post-genocide, to the aftermath of the civil and ethnic war in which close to a million people lost their lives over a period of three months. Her efforts to discover for herself the fate of each of her Rwandan colleagues is simultaneously riveting, wrenching, and uplifting.

Novogratz’s creation of the Acumen Fund is a logical next path in her quest to apply business principles to social change: The venture capital fund invests in social entrepreneurs working to help the world’s poor. In this section she highlights the early years of the fund, its underlying principles, and her exposure to Asia, specifically to remarkable entrepreneurs who are my heroes, too: the late Dr. Govindappa Venkataswamy, founder of Aravind Eye Hospital; Satyan Mishra, founder of Drishtee; Amitabha Sadangi of IDE-India; Tasneem Siddiqui, founder of Saiban; and Roshaneh Zafar, founder of the Kashf Foundation.

And there the book ends, its readers left wondering what path this “ordinary” extraordinary woman will take next.

So that they will succeed as well as she has in their own missions, I hope readers also take away that ultimately, the book is a wonderful lesson in the importance of empathy—not one that comes from a place of superiority, but one born from a profound humility and belief that from her to whom much is given, much is expected.

Pamela Hartigan is the director of the Skoll Centre for Social Entrepreneurship at the University of Oxford’s Saïd Business School. She is the coauthor of The Power of Unreasonable People: How Social Entrepreneurs Create Markets That Change the World.