_-_28de80_-_2168286de762092e560678d98d72e9eac02dc9a4.jpg)

Deeply Divided: Racial Politics and Social Movements in Post-War America

Doug McAdam & Karina Kloos

408 pages, Oxford University Press, 2014

By many measures–commonsensical or statistical–the United States has not been more divided politically or economically in the last hundred years than it is now. How have we gone from the striking bipartisan cooperation and relative economic equality of the war years and post-war period to the extreme inequality and savage partisan divisions of today? In the book from which this excerpt is taken, we provide an original and provocative answer to that question. The excerpt is intended to serve as but the briefest sketch of that answer.

How Did We Get Into This Mess?

When Barack Obama captured the White House in 2008 there were many who heralded his victory as marking the long overdue onset of color blind politics in America. As NPR reported, “The Economist called it a post-racial triumph… [and] the New Yorker wrote of a post-racial generation…”1 Sadly, the widely advertised post-racial society never quite materialized. Indeed, a growing body of evidence suggests that, if anything, the influence of what Tesler calls “old fashioned racism” has grown considerably since Obama took office.2 Furthermore, those hoping that Obama’s presidency would begin to moderate the extreme partisan tensions of the Bill Clinton and George W. Bush years and perhaps even bring about greater economic equality have been disappointed. The harsh reality is that for all its historic significance, Obama’s presidency has done little to reduce the country’s underlying racial, political and economic divisions. America’s racial politics will come in for a great deal of attention in this book. We begin, however, by considering these other two central features, the extreme economic inequality and unprecedented partisan polarization that mark contemporary America. The country is now more starkly divided in political terms than at any time since the end of Reconstruction and more unequal in material terms than roughly a century ago and greater, even, than on the eve of the Great Depression.

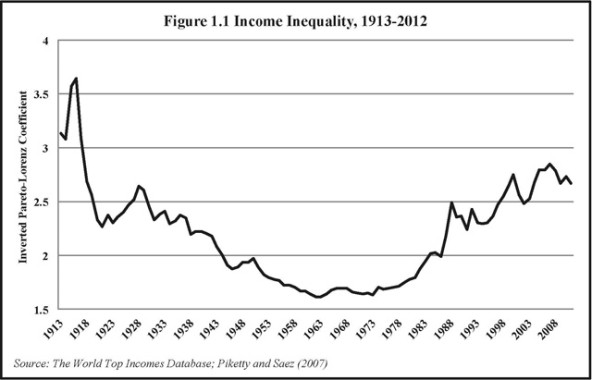

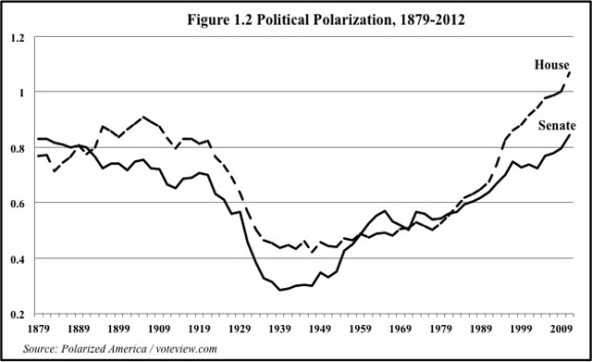

In Figure 1.1 we use research by two economists, Thomas Pikkety and Emmanuel Saez, on income inequality to map fluctuations in the economic gap between America’s haves and have nots since 1913, which is as far as the data go back. Figure 1.2 shifts the focus from economics to politics. For better than 30 years, political scientists, Keith Poole and Howard Rosenthal have refined the analysis of Congressional voting into something of an art. Using their spatial model of voting, they have been able for the entire history of Congress to map the left/right oscillations in both the House and Senate and to assess just how ideologically close or far apart the two parties have been at any point in our history. Using the Poole and Rosenthal data, Figure 1.2 maps partisan polarization in Congress since 1879.

This latter figure confirms the deep political divisions that characterize the present-day U.S. In truth, we probably didn’t need the Poole-Rosenthal data to know just how divided we now are. The events of the past six years—serial budget crises, government shutdown, willful sabotage of presidential appointments, etc.—have told us all we need to know about escalating paralysis and government dysfunction. Just how bad has it gotten? Consider that, as of October 2013, one in three Americans identified government dysfunction as the “most important problem” confronting the country.3 While the percent of subjects concurring in this judgment had increased steadily over the course of the Obama presidency, never before had a plurality of respondents identified “government/Congress, politicians” as the country’s most pressing problem. This finding coupled with a close examination of the last few years of the Poole-Rosenthal time series highlight the sad reality: far from waning, partisan polarization has escalated sharply since Obama took office. The same is true for economic inequality. A growing body of studies now confirms that income inequality has also jumped significantly on Obama’s watch.4

We will devote a great deal of attention to these two defining features—political division and economic inequality—of the contemporary American political economy, documenting both and assessing the links between them. As our title suggests, however, the central question that motivates the book is about origins and the complex history of American politics since roughly the onset of World War II. How did we go from the striking bipartisan cooperation and relative economic equality of the war years and postwar period—clearly reflected in the above figures—to the extreme inequality and savage partisan divisions of today? We offer a stylized answer to this question in this first chapter, devoting the balance of the book to a detailed historical narrative designed to document and elaborate the broad-brush stroke account offered here.

On Parties, Movements and the Rise and Fall of the Median Voter

In recent years, a growing chorus of political commentators has lamented the absence of anything resembling a bi-partisan “middle” in American politics. What a difference a few decades make. While it is now commonplace for political analysts and observers to celebrate the strong, bipartisan consensus that prevailed in the postwar period, there were those at the time who saw the dominance of moderates in both parties as a kind of tyranny of the middle. Whatever one’s normative take on the centrist tendencies of the era, the received wisdom among contemporary scholars was that the two party, winner-take-all structure of the American system virtually compelled candidates—especially presidential nominees—to hue to the center if they hoped to be elected. In his influential 1957 book, An Economic Theory of Democracy, Anthony Downs argued that in a two-party system candidates could be expected to “rapidly converge” on the center of the ideological spectrum “so that parties closely resemble one another.” Introduced a year later, Duncan Black’s Median Voter Theorem, represented a highly compatible, if more formalized, version of Downs’ “convergence” theory. For several decades thereafter this general model of voting was thought of as akin to a natural law when it came to U.S. politics, especially in elections involving large numbers of voters. Since the ideological preferences of voters were assumed to be distributed normally around a moderate midpoint, any candidate adopting a comparatively extreme position on the liberal to conservative continuum would seem to be easy prey for a more centrist candidate.

The central puzzle for us is how did we get from the seeming “natural law” of the median voter theorem to the decisive power wielded by ideological extremists, as exemplified by today’s Republican Party? There is now a substantial literature—rooted in scholarship, but much of it written for a popular audience—that purports to answer this question. The problem is the literature focuses almost all of its attention on the shifting fortunes of the two major parties and the vagaries of electoral politics. Its main story lines include the loss of the white South by the Democrats in the 1960s, Nixon’s success in wooing disaffected Dixiecrats in 1968 via his “southern strategy,” and the thunder on the right of the Reagan Revolution of the 1980s. These are critically important chapters of the broader story and, as such, will come in for a great deal of attention in later chapters. The lacuna is not what the literature focuses on, but what it almost always omits. The omission reflects a longstanding, if unfortunate, disciplinary division of labor when it comes to the analysis of American politics. In general, the otherwise impressive literature on the development of today’s distinctive U.S. political economy has been impoverished by its almost total neglect of social movement dynamics. Yes, the electoral realignment of the South occasioned a tectonic shift in American politics and moved both parties substantially off center politically. And yes, Reagan’s two-term presidency not only deepened partisan divisions, but also accelerated the economic trends that have left us so fundamentally unequal today. But to represent these features of the present-day political economy as byproducts of party politics alone—which is what most scholarly accounts tend to do—is to badly distort the more complicated origins of the mess in which we find ourselves. All of these features of contemporary U.S. politics have been—and continue to be—powerfully shaped by the interaction of movements, parties, and governmental institutions. The best scholarly work on contemporary American politics continues to be done by political scientists, but reflecting the aforementioned disciplinary divide, political scientists tend to focus their attention exclusively on political parties and institutions and leave the study of social movements or other forms of non-institutionalized politics to sociologists. This means that the crucial role played by social movements in the evolution of the American political economy since the 1960s has been almost completely neglected in even the best work on the topic. This book is our attempt to at least partially redress this glaring omission.

We begin with a stark theoretical claim: the convergence perspective of Downs and Black (among others) only holds under conditions of general social movement quiescence. If we are right in this claim, it carries with it important empirical implications for an understanding of the extent of bipartisan consensus in the postwar period as well as the collapse of that consensus and the increasing polarization which has followed. Owing in large part to the “chilling effect” of the Cold War and McCarthyism, the immediate postwar period was uniquely devoid of significant social movement activity. This spared the two parties the centrifugal pressures that can follow when mobilized movement elements seek to occupy their ideological flanks.

By revitalizing and legitimating the social movement form, the civil rights movement of the early 1960s reintroduced these centrifugal pressures to American politics. Or more accurately, it was one movement—civil rights—and one powerful countermovement—white resistance or as we prefer, “white backlash”—that began to force the parties to weigh the costs and benefits of appealing to the median voter against the strategic imperative of responding to mobilized movement elements at their ideological margins. Owing in part to the tight control they exercised over national conventions and the selection of presidential candidates, the parties were able to manage these pressures for a while, but this became increasingly more difficult with the convention and primary reforms of the early 1970s. To fully appreciate the difficulties the two parties have had in managing these pressures is to begin to understand just how we got from the centripetal pressure of the medium voter to the centrifugal force of today’s extreme partisanship.

Besides the tug of war between parties and electorally attuned movements, our story turns centrally on the sustained significance and powerful structuring effect of race and region on American politics. More accurately, it is the interaction of these three forces—race, region, and movements—that have overwhelmingly shaped the evolution of American politics from 1960 to the present. We begin with race. Virtually all of the major movements that will take their turn center stage in our narrative—civil rights, white backlash, New Left, Tax Revolt, Christian Right, Tea Party—bear the very strong, if variable, imprint of race. So it is the shifting vagaries of American racial politics—channeled and expressed through a series of electorally attuned movements—that will propel much of our narrative forward.

Then there is the matter of region or, more specifically, the disproportionate political and electoral significance of the “solid South” throughout most of the 20th Century. But here again, it is the interaction of these factors, not their independent effects, that is the key to our story. Region and race, after all, have long been inextricably linked in the structuring of American politics. Or put another way, it is race that has long accounted for the “solidity” of the South’s political/electoral loyalties. It was the white South’s hatred of the Republican Party—the despised “party of Lincoln”—that bound the region to the Democrats for a century following the close of the Civil War. And it was white southern anger at the Democratic Party’s embrace of civil rights reform that set in motion the slow, but steady, process of regional realignment that by the 1990s had made the South the geographic foundation of today’s GOP and, importantly, its Tea Party movement wing. In short, the complex interplay between region, race and movement-party dynamics will continually inform and structure the story we have to tell.

Reprinted from Deeply Divided by Doug McAdam and Karina Kloos with permission from Oxford University Press USA. Copyright © Oxford University Press, 2014 and published by Oxford University Press USA. (www.oup.com/us). All rights reserved.