America was shocked in 2014 to see the video of Professional football player Ray Rice knocking his then-fiancée Janay Palmer unconscious in an elevator. Many lucky people who have never seen or experienced intimate partner violence didn’t realize what “domestic abuse” could really mean. But for those who work in the field of victims’ services—which is only about 40 years old—it was a reminder of the vast amount of progress we still need to make. With one in four American women experiencing domestic violence in her lifetime, we need more awareness, more services, and more choices for people in violent situations. It was with this sense of urgency that the nonprofit Safe Horizon, the leading victims’ services organization in the United States, embarked upon a strategic plan in 2015.

With a budget of $55 million, more than 50 locations in the five boroughs of New York City, and 600 staff, Safe Horizon provides comprehensive services to survivors of domestic violence, child abuse, human trafficking, and sexual assault, touching the lives of 250,000 people each year. Safe Horizon was founded in 1978 and grew rapidly by achieving excellence in attracting government contracts (which provide approximately 88 percent of the organization’s total funding), as well as private support. In fact, it was listed as number 137 in the classic 2007 article, “How Nonprofits Get Really Big.”

In the five years following its 2010 strategic plan, Safe Horizon gained a lot of ground. It became more focused on its core businesses, increased program standardization, implemented a client-centered approach, become increasingly evidence-based, engaged in effective fundraising, made major improvements in infrastructure, reduced its costs and boosted efficiencies, and continued to further its position of national leadership. Yet despite these advances, it saw only modest budget growth. It began to ask how the organization could grow further (its target population still had major unmet needs) while becoming more sustainable and less resource-constrained.

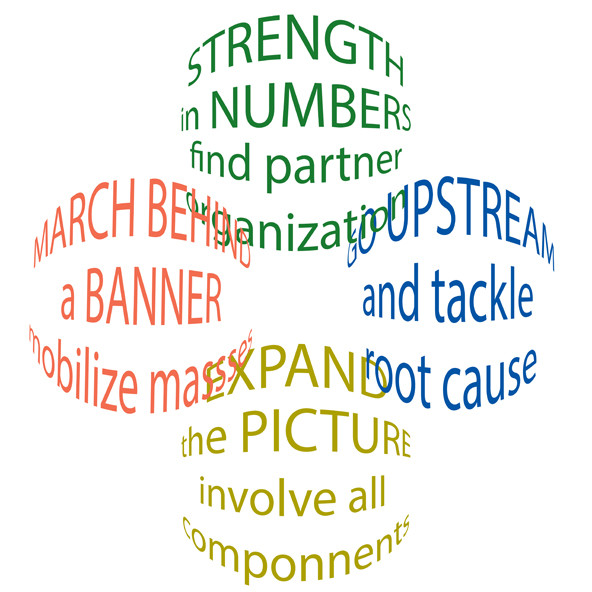

To explore possible approaches, Safe Horizon engaged Wellspring Consulting to undertake a new strategic plan in 2015. In the process, we explored four possible approaches employed by other organizations that might help build Safe Horizon’s brand, breathe new energy into the organization, and access new sources of funding—all in a fiscally responsible and sustainable way.

Are you enjoying this article? Read more like this, plus SSIR's full archive of content, when you subscribe.

1. Go Upstream

The National Audubon Society began with the mission of protecting birds and their habitats in the United States and worked largely on wildlife conservation policy, but over time, it became clear that protecting habitats in the United States also meant addressing the broader issue of global climate change. An organization using the “go upstream” approach serves its mission in part by pursuing the root causes of the issues it wants to solve. For the National Audubon Society, going upstream entailed developing a general focus on environmental protection, with the downstream goal of saving birds’ habitats.

What could this approach mean for Safe Horizon? Going upstream might mean addressing issues that help perpetuate the cycle of violence, such as poverty; though domestic violence affects people at all socio-economic levels, it most heavily affects the poor. More than half of all women on welfare have experienced domestic violence, and women with household incomes of less than $7,500 are seven times more likely than women with household incomes over $75,000 to experience domestic violence (Hetling & Zhang. Social Science Quarterly, December 2010). Furthermore, half of homeless women and children are fleeing domestic violence.

Alternately, Safe Horizon could work with a traumatized population it has not previously focused on, such as young men of color, who are more likely than any other demographic group to be victims of crime. Those who have been victims of crime often do not get the help they need, because few services exist to address their specific needs. These men are more likely to live with unaddressed symptoms of trauma, which can have significant implications for health, education, employment, safety, and cost to society.

2. A Banner to March Behind

The underlying assumption of this approach is that to make a difference, organizations must mobilize the public by developing awareness of and fostering a sense of outrage about a given issue. The March of Dimes, believing that medical research alone wouldn’t accomplish its mission to decrease birth defects and pre-term birth, created the walkathon concept to empower the public to raise awareness and funding. Since the organization began in the 1960’s, public outcry resulting from its campaigns has had a huge impact, contributing to the creation of newborn screening policies and laws, and warning labels for pregnant women on alcoholic drinks, among other advances.

Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD) uses a similar approach in its mission to reduce alcohol-related traffic accidents, mobilizing the public to speak out and take public action to end drunk driving. Campaigns urging people to give their car keys to a sober friend when drinking, and others, have helped drive progress: Annual alcohol-related traffic fatalities have dropped from an estimated 30,000 in 1980 to fewer than 15,000 today, and more than 2,000 laws to reduce drunk driving have been passed in the last 30 years.

Safe Horizon’s “banner” might take the form of a campaign with three defining elements: raising awareness about the prevalence of family violence and dispelling many of the myths associated with it, motivating people to act, and presenting a compelling solution to the public for how to combat the problem.

3. Expand the Picture

This approach posits that to make a difference, organizations must engage with all aspects of the problem so that they are part of the solution, instead of focusing on just a narrow piece of the problem. TerraCycle, which focuses on eliminating waste, started out by transforming food waste into quality fertilizers. As it saw landfills continue to pile up, it decided to take on many more kinds of waste, producing new consumer products from items that traditionally can’t be recycled, such as toothbrushes, drink pouches, and chip bags. TerraCycle also has a program for people to mail non-recyclable waste to the organization for free.

For Safe Horizon, expanding the picture might mean working not only with victims of intimate partner violence, but their entire family—including the abusive family members in appropriate cases. We know many victims who leave an abusive relationship eventually return, and even after a permanent separation, shared parenting often requires continued contact. Helping the full family is one of the most frequent requests we hear from victims, but our research indicates that this approach is under-supported by victim service organizations.

4. Strength in Numbers

The premise here is that one organization can’t make a significant difference on large issues by itself, and that working together with others with similar missions increases impact exponentially. Thrive Networks, formerly East Meets West, began as an organization dedicated to providing grassroots humanitarian aid in Vietnam. It soon realized the problems it faced were too substantial for the organization to tackle alone, and thus began to build a network of similar organizations that share back-office capacity and learn valuable skills from one another. Today, Thrive Networks partners with dozens of organizations. It has helped build schools and medical centers, provide life-saving medical treatments, and create sanitation systems—services that affect hundreds of thousands of people in Southeast Asia.

Safe Horizon might consider creating a network of similar organizations, or employing a regional or national expansion strategy. While partnering with existing organizations for geographic expansion would be risky, the organization could potentially develop a proven program model that others would seek out and replicate.

Conclusion

In the end, Safe Horizon decided to “go upstream” and “expand the picture”—to look at the other factors contributing to family and community violence and to engage all components of the problem in developing a solution. The story of violence begetting future violence has Safe Horizon putting more of an emphasis on working broadly with those who have experienced trauma—and working to heal their trauma now—so that they are better able to live full and safe lives in the future.

This will include piloting trauma-focused care to whole families, including batterers with whom victims choose to stay, when deemed appropriate, so as to prevent further abuse. And the compelling story of homelessness and poverty exacerbating domestic violence has led us to envision new programs in financial literacy, job training, and possibly even permanent supportive housing. Finally, we are initiating programming specifically focused on young men of color who are victimized by crime.

These four approaches can provide a valuable foundation for exploring a range of possibilities, leading to thoughtful idea generation and strategic decision-making. By advancing its work in this way, Safe Horizon expects to attract new sources of funding. And these approaches certainly have helped Safe Horizon make groundbreaking decisions for its future; we can imagine a future society free of violence because of the steps we are taking.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Rachel Light & Ariel Zwang.