Big social impact organizations occasionally draw big press, but the story is often one of failure, fraud, or deception. The Red Cross weathered a scandal invoking all three when NPR and ProPublica accused the organization of bungling its response to the 2010 earthquake in Haiti. The ProPublica headline that hooked readers was “How the Red Cross Raised Half a Billion Dollars for Haiti and Built Six Homes.” The story struck a chord with the public, gathering more than 800 comments between the two sites and inciting dozens of similar articles in publications such as Salon, TIME, and the Washington Post.

The Red Cross responded by saying that competing land claims and other setbacks meant that building new permanent homes wasn’t the most efficient and effective way of helping displaced residents. The organization instead focused on providing emergency shelter and transitional homes to meet immediate needs. It also explained that of the $488 million raised for its work in Haiti, $145 million went to health, cholera prevention, and water and sanitation services. While it appears the Red Cross did not live up to public expectations, the over-the-top media coverage painted the organization as an inept swindler.

This isn’t new. Stories of nonprofit wrongdoing easily gain traction and draw widespread condemnation, even when the details aren’t cut and dry. Social impact organizations are all vulnerable to nearsighted criticism, often centered on executive pay and program expenses. St. Louis Today recently published an article on how local nonprofits were “minting millionaires.” Allegations of executive greed and excessive compensation crop up frequently, but investigation from one of the sector’s foremost watchdogs reveals that such cases are rare. Charity Navigator’s 2014 Charity CEO Compensation Study gathered data from 3,927 nonprofits. Of these, only 12 offered compensation packages over $1 million to their top executive. That’s 0.31 percent. Furthermore, all of these seven-figure packages were collected by CEOs of large organizations with more than $13.5 million in revenue.

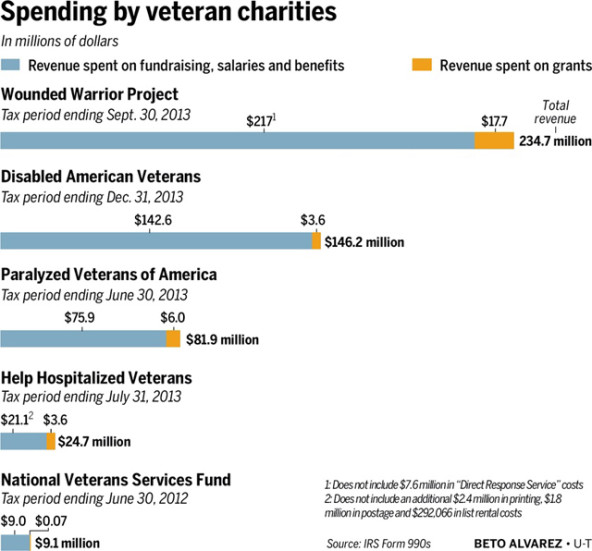

Press outlets also mislead readers by manipulating program spending data. For example, the San Diego Union-Tribune’s story, “Veterans Charities Don’t All Make the Grade,” included a graphic representation of how much revenue certain organizations spent on grants in 2012-2013.

The San Diego Union-Tribune included this misleading graphic in an article on nonprofits serving veterans.

The San Diego Union-Tribune included this misleading graphic in an article on nonprofits serving veterans.

Are you enjoying this article? Read more like this, plus SSIR's full archive of content, when you subscribe.

The graphic doesn’t mention that grants are just one of many ways these nonprofits serve veterans. The Wounded Warrior Project, for example, provides mentorship programs, alumni events, assistance with filing for veteran benefits, mental health services, inclusive and adaptive sports, and career guidance, among other programs. Its 2013 annual report lists program services expenses as $175,009,142. The implication that the organization spent $217 million on fundraising and staff salaries is plainly false.

Although exposés are popular news items in general, nonprofits are especially vulnerable to accusations of betrayal, greed, and failure. Why does the public love to read, share, and comment on criticisms of charitable organizations? Why are people so eager to believe the worst of nonprofits?

The obvious answer is that we love to see falsely lauded people or institutions cut down to size. But there are several documented attitudes toward charity that make social impact organizations prime targets of slander and derogation. The widespread belief in the norm of self-interest along with mistrust of “do-gooders” puts nonprofits and their staff under constant suspicion of wrongdoing. Meanwhile, the public’s view of nonprofits as less competent than for-profits puts heightened scrutiny on impact and compensation. To protect themselves from these prejudices, organizations must first be aware of them and then take action to subvert them.

The Norm of Self-Interest

One of the biggest factors predisposing the public to mistrust nonprofits and their staff is the norm of self-interest. The idea that individuals act to increase their own utility is deeply ingrained in the popular dialogue around economics, evolution, and social policy. In “The Norm of Self-Interest,” Stanford psychology professor Dale T. Miller explains that the public not only sees self-interest as the go-to explanation for behavior, but also a directive by which people should live. Society teaches us that it is normal and rational to do whatever results in our own material gain. In reality, research has found that self-interest is only weakly linked to attitudes on social issues, such as racial integration.

The idea that self-interest does (and should) direct action persists, though. Studies detailed in The Science of Giving by Daniel M. Oppenheimer and Christopher Y. Olivola suggest that this leads people to feel uncomfortable taking a stand for a cause that doesn’t directly affect them. A series of experiments on how the public perceives volunteers found that “the expectation that others will act in self-interested ways can lead observers … to respond with greater negativity toward supporters of a cause who do not have a victimhood experience that connects them to the cause.”

Nonprofit staff, who often work on causes that don’t directly affect them, can appear as if they are breaking this fundamental social norm. This breeds discomfort, suspicion, and even hostility. We see someone working for the good of others and ask, “What are they getting out of this?”

This is one driver of the scrutiny on nonprofit compensation. There are many news stories that portray nonprofit organizations as deceiving donors simply because the employees collect a paycheck. While six-figure salaries don’t necessarily inspire donors to give, they are not out of line for professionals running multi-million dollar organizations. Nonprofit executives are criticized for accepting compensation packages that would be laughably small at a for-profit business.

Professionals in the sector also know that nonprofit staff wages have actually suffered greatly in recent years. Non-executive staff have fallen victim to the rise of the overhead obsession. But with the underlying suspicion of people breaking a social norm, the story gains a foothold.

Do-Gooder Derogation

Another factor predisposing people to criticize nonprofits is the moral insecurity many feel when confronted with “do-gooders”—those who break a social norm in the name of morality.

A study on the documented hostility toward vegetarians revealed that when someone acts differently from the norm and attributes it to morality, others assume that the actor is negatively judging them. People assume that the “do-gooder” is questioning their morality.

For example, let’s say Daniel turns down a job at a big corporation because he is morally opposed to the environmental damage its manufacturing processes cause. Daniel’s friend Tracy, who already works for the company, may then assume that he perceives her as less moral, even if he says nothing about her choice to work there. Study participants who anticipated vegetarians negatively judging them rated them more negatively.

In short, people are more critical of those they think are looking down on them. Along with the norm of self-interest, this leaves the public uncomfortable with a nonprofit professional’s perceived transgression and eager to undermine any feeling of moral inferiority. It is possible that when the general public considers someone who has devoted their career to charitable work, they assume these professionals feel morally superior. Portraying nonprofit staff as corrupt or greedy cuts them down to size and mitigates the moral threat.

Assumed Incompetence

Another explanation is that the public may think nonprofits are simply incompetent.

Research shows that nonprofit organizations are perceived as more “warm” but less competent than for-profit businesses. Simply manipulating an organization’s URL (“.com” versus “.org”) revealed these associations. Nonprofits then, are under extra pressure to prove their effectiveness. The complex issues charitable organizations address, however, make success difficult to quantify and communicate.

Because competence and effectiveness are often the main drivers of determining compensation, this difficulty in conveying effectiveness—along with existing competence assumptions—makes it easy to paint nonprofit professionals as overpaid.

Effects

The vitriol concerning nonprofit misbehavior is often out of proportion with reality. Unfortunately, the fear of being tricked and exploited is extremely effective at provoking public disdain. If readers do not closely study these stories of purported nonprofit scandals, clickbait articles can damage or even destroy the organizations they feature.

Members of the social impact sector and those who do not wish to continue a culture that hinders progress must resolve not to spread and support the kind of coverage that misleadingly slanders nonprofit organizations. While it’s tempting to condemn and distance one’s organization from the latest target, this only perpetuates a destructive cycle.

While there are certainly true incidents of deception, in most cases the problem is one of transparency and messaging. Because complex social initiatives are so easily misunderstood, it often seems more prudent not to explain impact outcomes or expenses to donors. But shutting down communications is what leaves social impact organizations vulnerable to these misleading exposés. Fierce transparency is the best defense against allegations of deceit.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Allison Gauss.