Accessible design is a relatively recent phenomenon, a true product of the twentieth century in that changing attitudes about disability and civil rights prompted design forms that had never been seen, such as bumpy surfaces on the sidewalk, or added new requirements and meanings for familiar objects such as ramps or slopes. The history of accessible design in the U.S. ranges from post–World War II scenes of veterans testing prosthetic limbs, to 1960s-era activists who conducted sit-ins to insist on widespread accessibility, to more recent experimental work in technology and graphics that boldly declare an aesthetic of disability pride. In the following excerpt from Accessible America: A History of Disability and Design, I explore the role of disabled people’s own voices in the past and present of access. —Bess Williamson

***

Figure 1. Black and white photograph of World War II veteran Pfc. Robert Langstaff, a uniformed soldier wearing metal dual hook-style prosthetic arms, demonstrating the “special controls” on a Ford motor car. Photograph ca. 1945, Science Service Collection, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.

The design changes we think of as “accessible” have resulted from much debate and discussion. The people who designed and used accessible products and buildings discussed them in terms of varying qualities of design, and thought deeply about what those qualities meant. Disabled veterans of World War II rallied around the poorly performing limbs they first received in military hospitals; when they found a sympathetic audience in Congressional hearings, they detailed the problems of limbs cutting their clothes or fitting uncomfortably. Their testimonies about personal choice in prosthetics helped them lobby for more support, leading to specialized cars and houses being included in their veterans’ benefits. An image from this time shows the close relationship between prosthetics and mainstream technologies associated with American manhood: notably, a veteran photographed wearing a prosthetic arm (figure 1) did not really need the specialized add-ons he was “testing” on a Ford automobile, since they were mainly focused on the brake, clutch, and gas pedals, but the visibility of both made for strong public messaging. These technological advances also came with a strong message about disabled people’s responsibility to adopt and use these tools to fit in. In the postwar era, the administrators of medical rehabilitation programs were some of the principal advocates for accessible architecture and design. At the University of Illinois in Urbana-Champaign, the site of the largest college program for students with disabilities, program director Timothy Nugent delivered the firm message that students would have to succeed in an inhospitable environment out of school. As a result, the priorities he and others set for 1950s and 60s-era architectural change were for acceptability and inconspicuousness. As a principal adviser on the first building standard that mandated architectural access, Nugent proposed a kind of bare-bones access that characterized government-mandated design throughout the twentieth century.

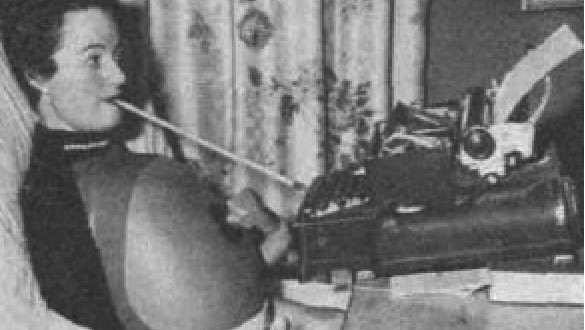

Figure 2. Newsprint photograph of Ida Brinkman, a dark-haired white woman wearing a curved medical respirator over her torso, holding a stick in her mouth in order to use a typewriter mounted on a desk over her bed. Toomey J Gazette, Spring 1959. Courtesy of Post-Polio Health International.

Disabled people’s own interventions into everyday designs have presented a parallel and sometimes divergent story line for access alongside the history of government mandates. In the relatively isolated contexts of home life in the mid-twentieth century, disabled people documented creative practices of adapting, repairing, or inventing technologies of access. In their own homes, with little help from medical or governmental authorities, disabled people and their families constructed usable technologies and environments for themselves. In one image (figure 2) from the Toomey J Gazette, a community magazine for polio survivors, Ida Brinkman, a young mother who had recently returned to her family, showed off the bed-based writing stand she could use in bed thanks to adjustments her husband had made to her respirator to make it less bulky. Holding a stick between her teeth to type, Brinkman presented herself as active and engaged in the world, rather than primarily through the lens of a medical condition. Home design projects like Brinkman’s typing desk were forerunners of the more consciously political moves of early disability rights activists, many of whom had, like Brinkman, been “rehabilitated” in polio hospitals and other medical institutions. In Berkeley, California, a key site for the early U.S. disability rights movement, the notion of self-advocacy informed a distinctive style of access that reflected the spirit of 60s-era activism. In Berkeley’s community-driven activism, “access” rarely stood alone as an architectural characteristic, but instead was part of a process of involving disabled people in aspects of planning, building, and policy making.

The accessible features that increasingly appeared in public in the U.S. were forms of design without designers, constructed with little input from the design professions: whether codified by program administrators like Nugent or designed through family and community work, the earliest ramps, curb cuts, and parking spaces were additions to already-designed environments, rarely meant to occupy attention as works of design or architecture. When they did capture public attention in the form of controversy over federal mandates, detractors identified what they saw as awkward forms resulting from government overreach. In debates over public transportation access in the 1980s, opponents of federal mandates used design as an argument against access. The principle of aiding a “special” population, opponents suggested, could not outweigh the cost and inconvenience of subway and bus alterations. This argument was a design statement in itself, as it identified the “public” for public transit as excluding disabled people. Even as mandates were expanded under the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, many advocates depicted a sympathetic individual consumer or taxpayer rather than a collective mass requiring public resources.

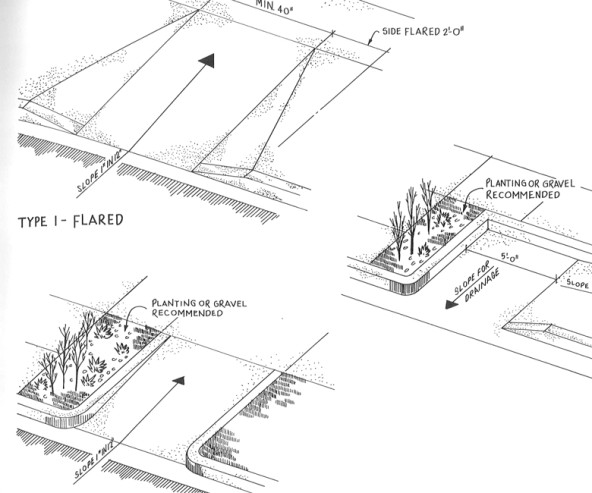

Figure 3. Ronald L. Mace, “Curbs,” drawing. Line drawings show three different curb cuts: “flared,” with a central slope and two slanted edges; “radiused” (marked as “*preferred”) with a defined curb next to the slope, accented by planting or gravel; and “parallel” with the ramp parallel to the street and planting on one side. From Ronald L. Mace, An Illustrated Handbook of the Handicapped Section of the North Carolina State Building Code (Raleigh, N.C.: North Carolina Dept. of Insurance, Special Office for the Handicapped, 1974).

If design was a scarce resource for critics of accessibility regulations, it also appeared as a salve against political turmoil at the end of the twentieth century. Proponents of “Universal Design” presented a more optimistic and generous vision of design that could serve both disabled and non-disabled users without compromise. Architect Ron Mace, who disseminated the term during a career spent writing federal accessibility regulations, considered it not as an alternative to accessible design, but an explanation that removing barriers could have a host of possible benefits. Mace’s work resisted the notion that accessible design needed to be a costly and inconvenient add-on. Even in his earliest work, including a series of illustrations created for the 1974 North Carolina Building Code (figure 3), Mace showed multiple options for new architectural requirements such as curb cuts. In the 1980s and 1990s, shapely consumer products and fashionable assistive devices further revamped the image of access with the ideal of an attractive and equitable form of “good design.” Presented as well-considered design that could benefit a broad population, the notion of Universal Design reoriented debates over the validity of disabled people’s claims to design inclusion.

***

In the fall of 2016, just months before the end of President Obama’s last term in office, the White House held a Design for All Showcase, a fashion show and panel discussion highlighting “inclusive design, assistive technology, and prosthetics.” Organized by the White House Office of Public Engagement, the show featured clothing and personal devices on the market or in development, modeled by disabled people. The show included jeans designed for seated wheelchair users, with added stretch and side closures; prosthetic arms and legs of a variety of vivid designs; and elegant braces sculpted for the body by 3-D printer. Some products suggested widespread possible use, such as shirts with magnet closures to avoid the use of buttons, while others responded to a more specific need, such as a line of T-shirts designed with fused seams and ultra-strong fabric that had been co-designed by MIT researchers with a young autistic woman who picks and frays her clothing apart. There was no single strategy of “universal” or mass-market appeal at the showcase, although this value was certainly on display with products such as an alternative system for lacing shoes from Nike that was developed by an intern with cerebral palsy. As the celebrity guest announcer described each product, certain familiar tropes appeared from the history of accessible design: the notion that a prosthetic leg allowed a veteran to “pursue his dreams,” or that clothing with easy closures created “independence” for its wearers. The language of rehabilitation was less present than the language of consumption, from the fashion show format to personal statements by individual users dressed up and performing for the spotlight.

Instead of a unifying aesthetic or design strategy, the organizing theme of the Design for All Showcase was the experience of disabled users. As each model spoke into the microphone, they tended to define the role of design in relation to a sense of identity. Blogger Annette Lamont started the show, rolling up in her wheelchair wearing ABL Denim adaptive jeans and stating that “fashion is my passion, and inclusive designs . . . provide ease of comfort without compromising my style.” Others spoke from the perspective of makers as well as users: a goth-styled figure named Peregrine said of his 3-D printed, open-source arm from Enabling the Future, “I wear this design because I designed it, I made it, and it’s me.” For others these design moves were part of professional identities, such as Sarah Fernandez, a lawyer modeling a leopard-print wrap dress from Kathy D. Woods’s collection of fashions for people with dwarfism, who said the garment gave her “the extra oomph to let people know I mean business.” Whether the clothes and devices were understated or elaborate in style, they presented design as a catalyst for new ways of thinking about disability. Kyle Garcia, an ex-Marine on his way to becoming a lawyer, said that his custom-designed leg cover in a matte black with orange details “shifts the conversation from disability to design.”

In this showcase, this shift “from disability to design” never departed from a focus on disability as a presence and design impetus. The show firmly positioned disability as a source for innovation in design. The venue of the White House also suggested that this form of inclusion was a part of civic identity and national industry. The Obama White House had made a particular point of showcasing disability within its public programming. In 2015 the president marked the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act with a meet-and-greet that included signed, typed, and video conversations, while the following year the White House’s South by South Lawn technology festival featured an exhibit of new and experimental disability technologies. Nowhere in the fashion show or the South by South Lawn festival did the White House identify disability-related technologies as a product of legal requirements. Instead, this was accessible design presented as a part of a technologically and socially-aware future.

The Design for All Showcase exhibited a hopeful techno-futurism that at once recalls post–World War II prosthetics experiments and also speaks to a current-day investment in design as part of the tech industry. In this tech-focused realm, disability is positioned as an innovative research area that leads designers to new technological discoveries, rather than a medical problem to be fixed or cured. In her work on access, scholar Tanya Titchkosky asks us to reconsider the common understanding of access as a form of asking—a “space of questions surrounding who belongs where, under what auspices or qualifications.” Instead, she asks us to consider disability itself as a form of access, “a concept that gives us access” to people, to experiences, to relations among people, and so on. In the case of the Design for All Showcase, disability applications gave access to a positive future vision of technology supporting the body in all its differences.

Titchkosky defines access in terms of relations between bodies—human and human, human and institutional, human and architectural—in a way that goes beyond the purview of the single object or building. My own definition is rooted in the artifacts of material change in the historical period of the mid- to late twentieth century, when people developed specific physical forms in response to historical developments including the rise of rehabilitation, broad-based redefinitions of rights, and the late twentieth-century backlash against social entitlements. As my book went to press, the disability rights movement has returned to the national spotlight as activist groups, especially ADAPT, agitated to oppose changes to Medicaid and the proposed repeal of the Affordable Care Act under President Trump. On one hand, these arguments reveal historical changes, as an organization once called “American Disabled for Accessible Public Transit” now uses the simplified moniker ADAPT to address a range of political issues of exclusion. Still, the U.S. health care debates reveal deep and unresolved issues of the last half century around disability rights. Namely, the notion of access in terms of physical change in isolation has proved an impossible design scenario. Concrete cracks, elevators break, and, as Berkeley activists showed in the 1970s, initial design installations may not function as they were intended, and need revision. Likewise, physical change without policy enforcement or broader social supports will amount to a design shortfall. Discussions about health care in U.S. society often center on questions of individual cost weighed against the overall social benefit; as in the public transportation conflicts that ADAPT first organized to protest, truly inclusive policy requires an acknowledgment that disability is an expected part of human life, not a tragedy or “special” consideration. Designing an accessible America—still a vision left unfulfilled—requires embedding design in systems that can support rights and equality in ways that go beyond the material.