To invest in a place—whether for profit or for public benefit, whether an urban neighborhood or a rural community—is to place a bet on the strength of that community’s economic and social fabric. It’s a bet on the community’s ability to absorb the capital, use it to attract more resources, recognize and make the most of latent opportunities, and persevere to create more opportunity and value That ability is a direct function of the cohesion and collective determination of the community’s residents, organizations, and political support.

Not every community has what it takes to pay off that bet. And not all investors have a clear idea of how to cultivate the readiness, the absorptive potential, that makes for an investable place. This explains the many communities where public and private dollars poured in, and a building or two rose, or a new service was offered, some new organization hung out a shingle, people in suits cut ribbons and declared a new era, and then… not much changed.

The story is sad, but it’s not inevitable. Over the years, communities that had seemed to lack the wherewithal to make the most of investments have later turned around, seizing opportunity and remaking the landscape, piling value on value. In places that were once thought resistant to change, in sections of Newark, Indianapolis, Oakland, Houston, and Chicago, among many other places, certain neighborhoods have managed to shift the odds. They have fundamentally improved their ability to use capital effectively, transform their surroundings, and build confidence among both investors and residents. The result: visibly better communities—more street life, better schools, stronger commercial strips, better housing, a heightened sense of safety and possibility.

Proud new homeowner in Chicago Lawn. (Photo by Bill Healy/LISC Chicago)

Proud new homeowner in Chicago Lawn. (Photo by Bill Healy/LISC Chicago)

How does this happen? Years of thought and experience—including many influential articles in this publication—have persuasively argued that the key is cohesiveness. It’s more than an initiative or two; you can’t get there just by building a new school or repaving Main Street or opening a job-counseling office. The key is to form the social and strategic ligaments that bind whole neighborhoods and help their centers of strength and energy work in concert.

Are you enjoying this article? Read more like this, plus SSIR's full archive of content, when you subscribe.

In stronger communities, local interests find ways to pull together, form networks, share information, take collective action on local issues, and forcefully promote their own understanding of local needs and opportunities to government and outside investors. An improved school is linked to the new clinic; the youth program and the merchants’ association work with police and the parks department; arts groups and economic development programs and housing associations find common cause.

If you find a way to forge these networks, many observers have counseled, you’ll cultivate fertile places for all kinds of capital, public and private.

At the Local Initiatives Support Corp. (LISC), the nation’s largest and oldest community development financial institution, we’ve never doubted that wisdom—in fact, it’s the driving force of everything we do. When we channeled corporate and philanthropic money, in partnership with public dollars, into well-organized communities, where we’ve worked with businesses and schools and block associations and human-service organizations to hammer out a shared agenda, the return was unmistakable: better education, safer streets, busier business districts, more desirable housing and public spaces. The improvements lasted and multiplied.

Students at Marquette Elementary School in the Chicago Lawn neighborhood. A focused partnership led by SWOP with school leadership has expanded community and parental engagement at the school and increased quality of educational performance. (Photo by Eric Young Smith/LISC Chicago)

Students at Marquette Elementary School in the Chicago Lawn neighborhood. A focused partnership led by SWOP with school leadership has expanded community and parental engagement at the school and increased quality of educational performance. (Photo by Eric Young Smith/LISC Chicago)

Still, when a wary investor or a skeptical public policymaker said, “Show us the numbers, where are the charts?” we had to rely on persuasive storytelling. We could walk them around a neighborhood, and that often worked. But we didn’t have the quantifiable data that it was the social networks, the integrated efforts of multiple local forces acting in concert, that made the difference. We couldn’t always persuade them that forming those connections was the right place to start and the best way to maximize results.

Part of the reason was that the social science and evaluation field had yet to catch up with the effort in a way that truly measured the work of forging networks. This is because every place is unique; every story is a little different; every successful network has its own mixture of driving forces and moving parts. We didn’t feel that research was able to quantify how disparate patterns of interaction can be galvanized into functioning engines of collective effort. Nor could we point to hard evidence that, whatever the particular variations from place to place, it was the formation of these networks, harnessing the concerted energies of whole neighborhoods, that counts.

Now we can.

MDRC Research Shows Importance of Social Networks

The first installment in an ongoing series of reports by MDRC, the preeminent social-policy research organization in the United States, has collected evidence from LISC’s decade-long New Communities Program in Chicago. Funded with more than $50 million in grants from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, plus hundreds of millions more in follow-on investments from other sources, New Communities Program has fostered just these kinds of whole-neighborhood connections in more than a dozen areas of the city.

MacArthur’s commitment represented one of the largest single-city community development efforts in the country, and their partnership with LISC helped spark a generation of comprehensive community initiatives, including LISC’s own Building Sustainable Communities effort and initiatives in the Obama White House. Focusing on seven of the New Communities sites and two other neighborhoods, MDRC used social network analysis to measure the structure and strength of local partnerships and then assess whether these connections could be associated directly with the success of neighborhood improvements.

Social network analysis is a way of mapping the relationships among people and organizations working in a given place or field. It provides a way of understanding where the strengths of the observed relationships lie and what they can accomplish. The analysis can tell us what becomes possible when the resources of several organizations are combined, in specific ways, compared with what any one of them could have achieved on its own.

Drawing from this analysis, the resulting Chicago Community Networks Study shows that LISC’s work can strengthen communities not just by working with an individual agency, but also by supporting the health and resilience of an entire network of community organizations. One of the ways that it does this is by identifying and supporting the work of a web of partners with the ability to work together well. And, it is just this web of connections that appear to matter. As MDRC sums it up:

“Education and housing networks with a set of well-connected core partners — each bringing their own resources and relationships to the table — appeared better able to develop community-school partnerships, commercial corridor development projects, business improvement districts, and corridor beautification activities.”

At least as important as these project-oriented partnerships were the coalitions that were created around public policy. Given the enormous power of city policy over the growth or decline of neighborhoods, the ability to work with and influence local government is among the most critical factors in a community’s capacity to absorb and leverage investment. Combining the two kinds of effort—public policy and service delivery—“may enhance both the quality of services and their ability to attract resources and partners,” MDRC concluded.

One small example the report cites is a program called the Parent Mentor Program, organized by the Logan Square Neighborhood Association in northwest Chicago. The program is part of a web of cooperative relationships in the community, roughly half of which link school-improvement activities with community organizing and advocacy. Parent Mentors placed local parents in classrooms as aides, but also mobilized them as organizers and campaigners for improvements in school policy. The researchers find that this fusion of direct action with effective advocacy, played out in many places, “reinforces the idea that an important component of comprehensive community initiatives may be engagement in both service delivery and public policy.”

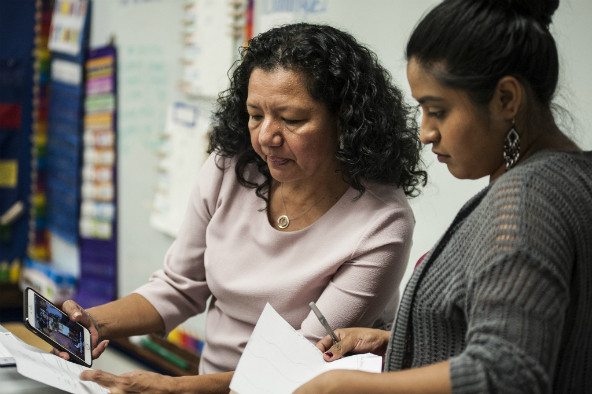

Logan Square Neighborhood Association’s Parent Mentor Program in northwest Chicago. The program is part of a web of cooperative relationships in the community, roughly half of which link school-improvement activities with community organizing and advocacy. Parent Mentors place local parents in classrooms as aides, but also mobilize them as organizers and campaigners for improvements in school policy. (Photo by Gordon Walek/LISC Chicago)

Logan Square Neighborhood Association’s Parent Mentor Program in northwest Chicago. The program is part of a web of cooperative relationships in the community, roughly half of which link school-improvement activities with community organizing and advocacy. Parent Mentors place local parents in classrooms as aides, but also mobilize them as organizers and campaigners for improvements in school policy. (Photo by Gordon Walek/LISC Chicago)

A detailed understanding of networks and their power, which MDRC has now crystallized, is crucial for anyone committed to helping communities recover from disinvestment, population flight, deepening poverty, and an atmosphere of powerlessness and despondency. Pulling together—in specific combinations, for particular purposes, with multiple interlocking sets of collaborative relationships—makes it possible to put capital to use in productive and durable ways.

These patterns strengthen the neighborhood’s ability to add one kind of value to another—improvements in health and education leading to rising employment; safer streets and better housing leading to greater business and employment opportunity; a more active citizenry leading to more responsive public services—and multiply the results over time. That is the hallmark of a place where it’s possible to invest with a realistic confidence that the intervention won’t be just a single shot, leading nowhere.

Besides recognizing what community networks can do, it’s also crucial to understand how they form and what patterns indicate strength and likely success. Here, too, the MDRC research sheds light on experiences that LISC has known, in practice for decades, but that we were unable to document quantitatively.

Beyond the Collective Impact Model for Connecting Organizations

One such pattern of formation and growth—which was first articulated in Stanford Social Innovation Review and has since been richly covered in these pages—is what’s known as collective impact: the powerful formation of collaborative alliances based on shared goals, strategically planned projects, and shared accountability, all arrayed around a central agency, called a “backbone,” that holds the organism together. LISC has used collective impact models in many places, with strong results.

But what happens in neighborhoods without a serviceable backbone agency? Many communities have an extensive web of accomplished organizations with solid records of achievement in their own domains, but without the breadth of relationships or elevated stature among their peers that would make any of them a forceful nucleus for the whole system. Again, LISC has had extensive experience with successful neighborhoods that lack such backbones, and yet still prove to be excellent targets for investment that pay off in all kinds of economic and social value.

MDRC’s network analysis now shows us why. Although the hub-and-spoke role of the backbone in collective impact clearly provides a firm locus for common planning and accountability, it’s not the only structure that works. It turns out that planning and accountability can also be ensured in other ways—sometimes by a group of partners with shared responsibility for governance and not a single agency. These leaders can ensure broad and organic engagement over time around a variety of issues, beyond any one collective impact project.

LISC has used something we call a quality-of-life planning process to instill and strengthen these kinds of self-sustaining networks. The process enlists representatives of the widest possible variety of local programs and organizations, from every available discipline, in defining and ranking needs and identifying near-term and longer-term opportunities. The groups may not—often do not—represent deep partnerships at first. They are collections of experience, vision, and talent that represents the community’s whole range of activity. But over time, what may be just a few real relationships of trust and collaboration begin to grow and spread. Success on early projects builds more trust; and that trust becomes the force that binds more and more of the centers of energy into an increasingly organic, durable whole.

The diversity of the participants is essential. That’s a fundamental principle that has been a cornerstone of community-development orthodoxy for more than a generation. But as the MDRC research confirms, truly diverse coalitions are hard to achieve and even harder to sustain. Without careful, patient guidance and artful problem-solving, the group’s very diversity exerts a centrifugal force, pulling people and organizations with different backgrounds and perspectives away from one another. Managing the differences, cultivating the skills of communication and problem-solving, and building the confidence and versatility of the individual members are all challenges for anyone who seeks to form or strengthen community networks.

That is where the New Communities Program—and LISC’s emphasis on comprehensiveness everywhere we work—shows a way forward. Here, the key factor is longevity and persistence, remaining engaged in the community, woven into the embryonic networks, and available to intervene or suggest workarounds when divisive pressures start to build. Our commitment to resident partnership with communities and neighborhoods—with local staff and offices, and personal participation in the planning and coordination of projects—gives us the bona fides and the firsthand relationships to play as much of the network-building role as the local players want and need from us.

The result, MDRC has found, is that in LISC’s Chicago neighborhoods, the diversity of the coalitions has become a source of strength and connectivity, not of division. “In contrast with findings from past research pointing to the challenges that diverse organizational types face when coordinating,” the MDRC researchers wrote, the current study “found that neighborhoods where partnerships spanned multiple work domains and included a broader range of different organizational types were often able to leverage these differences for more effective programs and policy, especially when these partnerships were intentionally formed and well managed.”

Consider, for example, Chicago’s Southwest neighborhood, hit hard by the explosion of residential foreclosures in 2008 and beyond, and burdened with extensive commercial vacancies and dwindling markets for local business. Nearly a decade later, Southwest was the neighborhood where MDRC found the largest number of working ties among organizations covering the widest array of different fields of effort. “A core set of actors managed this organizational diversity and comprehensiveness,” the researchers found, “and led the implementation of community projects related to foreclosure prevention and commercial corridor revitalization.”

No single backbone. No one prime mover (this was certainly not a LISC achievement alone). This was a broad-based fusion of skills and disciplines, reinforced by a gradual build-up of trust, that are now working effectively and in concert to “prevent foreclosure and quickly reoccupy foreclosed and abandoned buildings.” The members of this network, MDRC notes, “intentionally cultivated this diverse group of organizations in order to reach a broad set of constituencies.”

Chicago’s Southwest neighborhood was hit hard by residential foreclosures in 2008 and beyond. The Reclaiming Southwest Chicago campaign is a coordinated effort by SWOP and its partners to repair both the physical and social damage caused by the foreclosure crisis. The first step was rehabbing homes and putting them back on the market. (Photo by Alex Fledderjohn/LISC Chicago)

Chicago’s Southwest neighborhood was hit hard by residential foreclosures in 2008 and beyond. The Reclaiming Southwest Chicago campaign is a coordinated effort by SWOP and its partners to repair both the physical and social damage caused by the foreclosure crisis. The first step was rehabbing homes and putting them back on the market. (Photo by Alex Fledderjohn/LISC Chicago)

So, for instance, school principals have alerted housing and human-service organizations when families in their schools appear to be under stress, or when school personnel notice nearby properties that need attention from the local office of the nonprofit Neighborhood Housing Services of Chicago. And the links extend further outward, including strengthening ties to state and local government. Cook County, which includes Chicago, relied on its connections with Southwest housing organizations to find qualified purchasers of vacant and foreclosed properties. At the same time, a well-organized push by several neighborhood organizations led to an infusion of millions in new state funds to renovate less marketable housing stock.

A coalition of local businesses meanwhile established a business improvement district for the 63rd Street commercial corridor. But the catalyst for that wasn’t just an agreement among the businesses. The spark came from the closing of a police station, which brought the businesses and a large, citywide social-services organization together to convert the empty station into offices for the nonprofit. The results included one more link forged in the chain of collaboration—from business to government to nonprofit—along with the rescue of a derelict building and a stronger, more connected business association.

But the story of Southwest is only one anecdote among many. I raise it merely to illustrate the complexity of the dynamics here, and how they build over time. It’s important to emphasize that stories of particular neighborhoods discovering the value of networking and comprehensive development are not particularly new. The prolonged effort behind New Communities has surely made it possible to build larger, more intricate webs of interaction than might be common in other places. But organizations with a record of success in redeveloping communities have always been able to point a visitor to this or that illustration of what effective collaborative planning and integrated effort can do.

What’s new, at last, is that MDRC has created a method of analysis capable of dissecting this evidence, carefully and objectively compiled over a long period, and turning it into conclusions fit to be scrutinized by anyone who’s interested. And the value of that analysis is not only, or even mainly, that it confirms an approach to investing that we at LISC have believed in for four decades—gratifying as that is. The real value is that it may help to focus attention among everyone, public and private, who wants to invests in struggling or disadvantaged places and is looking for reliable ways to do it.

These possible investors may be drawn to all sorts of localities: neighborhoods that have been left out of the resurgence of their central cities, neighborhoods trying to preserve affordability under pressures from wealthier new arrivals, rural communities trying to marshal their assets to stave off loss of business and population—even places hit by natural disaster, scrambling to rebuild after catastrophic loss. In many such circumstances, investors may be poised to intervene, or might be enticed into doing so. But first, they will want to know that the soil is fertile, that the social and economic environment is capable of absorbing their investment and making the most of it.

They now know where to look for an answer: First, look to the interactive capacity to solve problems—where leaders and organizations are knit together in a network powered by communication, coordination, and collaboration, cemented by a rising level of trust, and extended, stage by stage, with increasingly ambitious projects. Where those strengths are lacking, then the first step is to build and fortify the connections and help them weave together into a network, and the opportunities for larger-scale investment will follow.

Where the interrelationships are present and working, the next step is to understand how they function, how far they extend, and what skills and expertise they bring together. Armed with that knowledge, it is possible to place smart bets, confident that the results will mark a measurable return for the community, and to continue to explore paths for further investment.

Many of us have believed that wisdom for a long time. Now, with a combination of decades of data and a fresh analytic approach to the critical questions, we’re beginning to be able to prove it.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Maurice A. Jones.