Facilitating Breakthrough: How to Remove Obstacles, Bridge Differences, and Move Forward Together

Adam Kahane

192 pages, Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 2021

The world needs more and better collaboration and therefore needs more and better facilitation.

The role of the facilitator is to strategize, organize, design, direct, coordinate, document, coach, and otherwise support the work of the group of people who are collaborating. This role can be played by anyone who is willing and able to help people collaborate to create change: a professional or an amateur; someone who is given this role or who takes it; a leader, manager, staff member, volunteer, organizer, chairperson, consultant, coach, mediator, or friend; someone who has a stake in the work at hand or is impartial; and a member of the group that is collaborating or someone from outside.

A facilitator helps a group, and the tension starts right there. The word “group” is both a singular and plural noun, and the task of the facilitator is to help both the singular group as a whole and the plural members of the group. This is the core tension underlying all facilitation.

Some facilitators deal with this tension by focusing primarily on the first part of this task: helping the group as a whole address the problematic situation that has motivated their collaboration. Other facilitators focus primarily on the second part: helping the diverse individual members of the group address the diverse aspects of the situation that they find problematic.

These two approaches, the vertical and the horizontal, are the most common and conventional approaches to facilitation. Both have their proponents and methodologies. Both can help a group collaborate to create change. But both also have limits and risks.

The excerpt outlines a third approach: transformative facilitation. The essence of this approach is not getting participants to move forward together but helping them remove the obstacles to doing so.—Adam Kahane

* * *

Most facilitators choose to employ either vertical facilitation or its polar opposite, horizontal facilitation. They argue that the approach they have chosen is more suitable and better than the other one. But when they make this choice, they inadvertently and inevitably constrain the potential of the collaborations they are facilitating, because neither of these conventional choices can create transformative change.

The vertical and horizontal approaches are, however, more than just opposite poles: they are complementary. This means that each of these approaches is incomplete without the other approach and that the downsides of each can be mitigated only through including the other. Facilitation can therefore only be transformative—can only break through the constraints of the vertical and horizontal—if the facilitator chooses to employ both approaches. This is the more powerful, unconventional choice.

The Facilitator Cycles Between the Vertical and Horizontal

The facilitator chooses both the vertical and horizontal poles the same way we all choose both inhaling and exhaling. Nobody ever argues about whether it is better to inhale or exhale. We cannot choose between them: if we only inhaled, we would die of too much carbon dioxide, and if we only exhaled, we would die of too little oxygen. Instead, we must do both, not at the same time but alternately. First we inhale to get oxygen into our blood; then, when our cells convert oxygen to carbon dioxide and the carbon dioxide builds up in our blood, we exhale to let the carbon dioxide out; then, when the oxygen in our blood falls too low, we inhale; and so on. This involuntary physiological feedback system maintains the necessary alternation between inhaling and exhaling and enables us to live rather than die. The crucial point about this rhythm is that inhaling and exhaling must each fall only partway into the downside before the body shifts to the opposite upside: if it fell all the way, the result would be death.

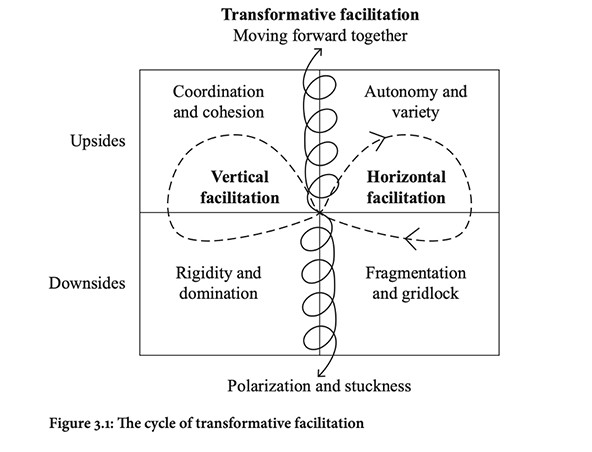

Transformative facilitation works the same way. Vertical and horizontal facilitation both have upsides and downsides (see figure 3.1). When excessive verticality starts to get the group stuck in rigidity and domination, the facilitator emphasizes plurality to move toward horizontal autonomy and variety. When excessive horizontality starts to get the group stuck in fragmentation and gridlock, the facilitator emphasizes unity to move toward vertical coordination and coherence. This attentive series of choices maintains the necessary alternation between the vertical and horizontal approaches (the infinity sign or lemniscate). The crucial point about this rhythm is that the facilitator must notice when their vertical or horizontal facilitation is falling part- way into the downsides, and at this point they must shift to the opposite upside: if the facilitation fell all the way, the result would be polarization and stuckness (the downward spiral). Cycling back and forth between vertical and horizontal facilitation produces facilitation that enables a group to move forward together (the upward spiral). This approach does not move in a straight line and is never straightforward.

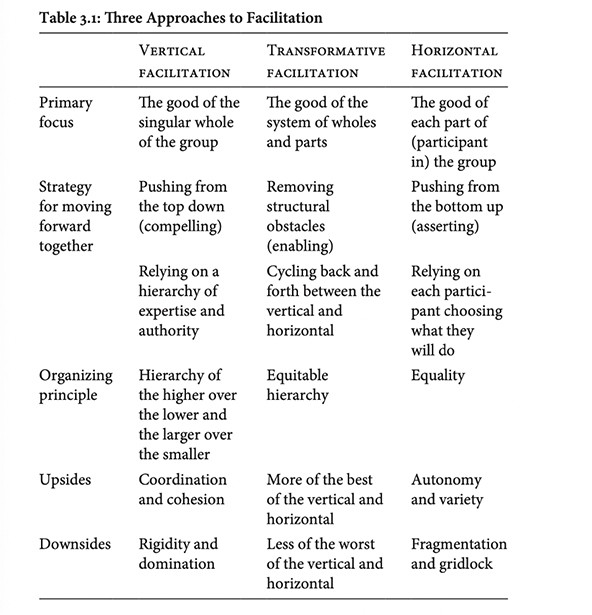

This third approach to facilitation is transformative (see table 3.1). It is not simply a mixture of or compromise between vertical and horizontal facilitation: it includes and transcends these two and transforms them into an approach that is fundamentally different. The constraints of vertical and horizontal facilitation mean that both of these approaches can only create limited change, but transformative facilitation removes these constraints by removing the obstacles to moving forward together (that is, by transforming the group). Only transformative facilitation can create breakthrough transformative change.

Cycling Removes Obstacles

Both vertical and horizontal facilitation focus on pushing through the structural obstacles to moving forward together, but transformative facilitation focuses on removing these obstacles. This approach to creating change has a long pedigree: in the 1940s, pioneering organizational development researcher Kurt Lewin posited that removing obstacles is more effective than increasing pressure:

Instead of simply applying pressure or forcing a change, Lewin’s research supports identifying and addressing restraining forces as a foundation for successful planned change: “In the first case [of applying pressure], the process . . . would be accomplished by a state of relatively high tension, [while] in the second case [of addressing restraining forces] by a state of relatively low tension. Since increase of tension above a certain degree is likely to be paralleled by higher aggressiveness, higher emotionality, and lower constructiveness, it is clear that as a rule, the second method will be preferable to the [first].”

In transformative facilitation, the facilitator makes both vertical and horizontal moves to remove structural obstacles to contribution, connection, and equity. The following are some examples of such structural changes:

- Setting up in-person and online working spaces to enable fluidity and creativity in who works with whom on what (through emphasizing flexibility and choice)

- Giving everyone an opportunity to collaborate with many different others (through working in multiple mixed small groups, along with informal breaks and meals and other ways to connect)

- Encouraging the rapid and participative generation and iteration of ideas (using physical and virtual flip charts and whiteboards, sticky notes, building blocks, and shared files).

In all these examples, the facilitator’s vertical moves are setting up new structures, and their horizontal moves are inviting participants equitably to employ these structures to contribute and connect all of their diverse concerns, ideas, commitments, gifts, and energies.

Cycling back and forth between the vertical and horizontal is like rocking back and forth a boulder that is blocking a stream, in order to dislodge it and enable the stream to run with greater coherence and flow. The facilitator employs five vertical and five horizontal moves to help a group move forward together with greater coherence and flow. These moves are introduced in chapter 4, explained in chapters 6–10, and summarized in A Map of Transformative Facilitation at the end of the book.

When a facilitator removes obstacles that block contribution, connection, and equity, they are performing a radical act. In many contexts, this act challenges the status quo, and participants who prefer the status quo will push back. To be successful in helping participants deal with such problematic situations, the facilitator needs to be aware of and respond strategically to dynamics that try to keep things the way they are. For example, dominant participants may try to impose their wishes on the group (through talking over others or using their authority to shape the group’s agenda or priorities), and in these cases the facilitator will need to negotiate group rules (including rules for making decisions) to ensure adequate contribution, connection, and equity.

Removing obstacles can also be a simple act. For example, the round of one-minute introductions at the beginning of the first Colombia workshop helped unblock contribution by enabling the voice of every person to be heard. It helped unblock connection by enabling everyone to see and hear everyone else. And it helped unblock equity by using the circle of chairs, with no one at “the front” of the room, and the one-minute bell, with no one given extra time because of their rank. This precisely designed first session set the pattern for everything that followed in the project. Transformative facilitation consists of simple actions undertaken with strategic intentionality.

Transformative Facilitation Enables Change in Organizations

Early in my career as an independent consultant, my colleagues and I facilitated a two-year strategy project for a Fortune 50 logistics company. The company’s established way of doing things was vertical: the CEO managed through giving forceful, detailed directives, which had produced the coordination and cohesion that enabled outstanding business success. But the COO thought that the company’s situation was problematic in that globalization and digitization were changing the competitive landscape, and he wanted employees from across the organization to collaborate more horizontally to create innovative responses.

My team worked with the COO and his colleagues vertically to agree on a project scope, timeline, and process, and to charter a cross-level, cross-departmental team. The process we designed for the team was more horizontal, participative, and creative than they were used to. They immersed themselves in the changes in their market by spending time on the front line of the organization, going on learning journeys to leading organizations in other sectors, and constructing scenarios of possible futures. They participated in workshops that emphasized full participation by all team members and that included structured exercises to generate, develop, and test innovative options.

This transformative process enabled breakthrough by creating a space within which the company’s culture of command and control, which assumed that the bosses knew best, was suspended. This enabled greater contribution by participants across different departments and from different levels in the hierarchy. The cross-departmental project team cut across the siloed organization, where lines of communication ran up and down rather than side to side, so the process enabled greater connection. And the company had a steep hierarchy of privilege, with senior people having much greater compensation and agency, so the process also enabled more equitable contribution and connection. Transformative facilitation enabled this team to come up with and implement a set of initiatives to launch new service offerings and to streamline company operations.

Transformative Facilitation Enables Change Beyond Organizations

In larger social systems that include multiple organizations of different types, the structures that encourage or constrain contribution, connection, and equity are larger and more complex than those within single organizations. Employing transformative facilitation in such systems therefore requires implementing strategic interventions to transform these structures, including through creating and growing new ones.

In our project in Colombia, for example, our first step was to convene the participants. The project initiators took many months to recruit leaders from all the region’s economic, political, social, and ethnic groups, including both the elite and the marginalized. They asked other influential people to endorse the project to give it credibility and to give the participants formal and informal authorization. They found an organization to fund the project and another to donate the hotel space.

The collaboration needed to be properly organized. We designed the project to provide support to the participants over the course of their work up to and during the first workshop and for the year that was to follow. We assembled a facilitation team that included the Reos team, with our international experience in facilitating such cross-organizational processes, plus locals with experience and relationships in the region. This team spent two days to get to know one another and to work out how to approach our role as facilitators.

To be able to work together, the participants needed to create enough of a common language to be able to talk about the situation in the region and how they could change it. We conducted open-ended interviews with each of them, both to enroll them in the project and to hear their views on the key issues facing the region. We then compiled these views into a report containing a selection of their unattributed verbatim statements, which we distributed in advance of the first workshop. On the first morning of the workshop, each participant presented their perspective on the current reality of the region, along with a physical object they had brought (these included a stone, a book, a seed, and a machete), which produced fresh metaphorical images. They used toy bricks to build models of the social-political-economic-cultural system of the region in its larger context, enabling them to share and combine their different tacit understandings visibly and fluidly. They wrote and organized their ideas on sticky notes, helping create and iterate their composite understanding of the current reality. All of these methodologies created space for all of the participants, including minority and marginalized ones, to express themselves equally and openly, and helped make visible some of what had been invisible.

Most crucially, the participants needed to be willing and able to work together. To support them in connecting better with one another, we agreed on a set of ground rules, especially about confidentiality, that helped them feel safer to make their contributions.

- Ate our meals together at long tables, which created a space for informal conversations.

- Invited them to go on walks in pairs, which enabled the development of personal connections across divides.

- Introduced a framework for open, nonjudgmental, empathetic listening, which they practiced in pairs; the final step in this exercise involved looking into their partner’s eyes, and the unfamiliar and unexpected sense of connection in the room was palpable.

- Facilitated an hour during which the participants told personal stories about their lives, which enabled them to understand better why some of them had ended up on opposing paths.

And we did all of these unconventional activities in a structured yet playful sequence, inviting the participants to relax and open up to what could happen—the expression of the mystery.

In everything our Colombian facilitation team did, then, we systematically employed both our vertical expertise and authority and the horizontal choices of the participants to remove the obstacles to contribution, connection, and equity.

In transformative facilitation, the facilitator cycles back and forth between the vertical and horizontal to unblock contribution, connection, and equity, and thereby to enable the group to move forward together. The next chapter explains the specific moves the facilitator must make to accomplish this cycling.