In Our Kids, Robert Putnam revives the lost art of bearing witness. He goes beyond raw data and listens to those who are otherwise voiceless in our society. By blending portraits of individual people with aggregate data, he gives us a remarkably clear picture of inequality in the United States. That accomplishment alone makes for a worthy read.

But the same generosity of spirit that fuels Putnam’s empathy causes the book to fall short in accounting for the powerful forces that have made widening inequality a fact of American life. If Putnam had written a similar book about “our climate,” it would leave the impression that the earth had merely drifted closer to the sun; it wouldn’t cover the human decisions and actions that have caused global temperatures to rise.

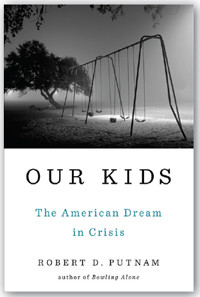

The town of Port Clinton, Ohio, where Putnam graduated from high school in 1959, is Ground Zero for his study of “the American dream in crisis.” He notes that 75 percent of his fellow graduates went on to attain a higher level of education and greater economic security than their parents had achieved. Because of socio-economic trends that range from the decline of manufacturing to residential sorting, that is not true of more-recent graduating classes. Complementing this decline in social mobility has been a decline in social solidarity. The book’s title reflects the time—now long gone—when people used the phrase “our kids” to refer not just to their own children, but to all kids in their community.

Putnam, a professor of public policy at Harvard University, ably uses demographic data to reorient our view of what’s gone wrong. The collapse of the working-class family that started to affect African-Americans in the 1960s, he notes, began to affect white Americans in the 1980s and 1990s. Since then, there has been a sharp decline in the ratio of US children overall who grow up in two-parent families, and the distribution of those children divides sharply along class lines. The proportion of kids with college-educated parents who live in single-parent families is less than 10 percent; for kids with working-class parents, it’s close to 70 percent.

What echoes loudest and longest in my mind, though, are the voices of the young people whom Putnam features. Consider David, an 18-year-old from Port Clinton whose father has been in and out of prison. “I’ll never get ahead!” David writes on his Facebook page. “I’ve been trying so hard at everything in my life and still get no credit at all. Done.” Or listen to Andrew from Bend, Ore., whose attitude toward the future reflects his comfortable upbringing: “My dad always reminds me every day how much my mom and my dad love me. … Some of my friends give me a wisecrack like, ‘Andrew’s parents say they love him again!’ But it’s like, yeah, that’s how I want it.”

In the book’s final chapter, Putnam imparts a lesson that he probably didn’t intend. He offers a list of proposed social programs that is so familiar that many readers will be able to mouth the words as if they were listening to a golden oldie: Increase the earned income tax credit. Invest in early education. Expand child care options. Promote mentoring. Other parts of the book hold up a mirror to our society, and this chapter is no diff erent: We are too timid, and too oblivious, to advance new or bold ideas about fighting poverty and inequality.

Even in Putnam’s capable hands, compelling research data and moving human interest stories are not sufficient. They don’t help us to understand the economic and political forces that perpetuate the crisis that Putnam describes.

Inequality has not widened on its own. Imagine walking into your house one evening to find drawers and closets emptied, furniture overturned, and nothing of value left. Would you conclude that socio-economic trends were responsible for that state of affairs, or would you note that a specific person or group of people had ransacked the place? Would your remedy be to encourage neighbors to think of every house as “their house,” or would you want to find and stop the perpetrators before they struck again?

Millions of poor children are suffering because of decisions we have made—decisions about how we tax and how we spend, who is first in line for support and who is last. On our list of priorities, we’ve put children’s needs so far below tax loopholes, entitlements, corporate bailouts, defense spending, and foreign intervention that no one actually has to say “no” to kids. We can take the easy option of shaking our heads sadly as we explain that there just isn’t anything left for them.

Putnam’s compassion for “our kids” is infectious. Here’s hoping that his book will help generate the political will to do more for them. After all, everyone likes to say that “children are our future.” But the call to change how we treat them will be more effective if we clarify what happened: The shabby house where they live didn’t just deteriorate, it was robbed.