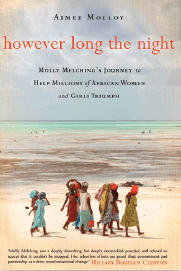

However Long the Night: Molly Melching's Journey to Help Millions of African Women and Girls Triumph

Aimee Molloy

272 pages, Harper One, 2013

At first glance, given its title and given some of the language on its cover, However Long the Night seems as though it might be yet another story about a person of privilege who leaves behind her dull life in Middle America and moves to Africa, where she hopes to help impoverished people and (not incidentally) to begin a journey of self discovery. So it comes as a pleasant surprise to find that the author, Aimee Molloy, has written a story not just about one woman, but about one organization—an organization that has worked diligently over many years to promote lasting social justice. The story of Molly Melching, in short, serves as a lens through which readers can observe the dynamics of community-activated change.

In 1991, after contributing to various social change efforts in Africa, Melching founded Tostan, an organization that has become well known for significantly reducing the practice of female genital cutting in Senegal. In the West African language of Wolof, “tostan” means “to hatch out of an egg;” the term evokes that breakthrough moment metaphor that conveys Tostan’s approach to community development, which focuses on collective consciousness raising: As ordinary people acquire knowledge in a way that empowers them, they eagerly share that knowledge with others in their community. Change thus happens from the ground up, through mutual respect and shared learning.

At the center of Tostan’s method is the Community Empowerment Program, a popular education initiative that covers topics of immediate relevance to people in Senegalese villages—preventing child mortality, for example, or managing local projects. The goal is not only to promote literacy and numeracy skills, but also to empower villagers to run their own development efforts. Tostan’s workers understand that the failure of a development project often involves distrust and disempowerment at a personal level, especially among women.

Some 2.1 million people from 2,643 villages, working together with 108 Tostan employees, have taken part in Tostan-led efforts to improve access to education, health care, and economic opportunity—and, equally important, to improve the conditions of women and young girls. Success of this kind, we learn, is almost never predicated on the charisma of a single leader. For leaders like Melching, humility is essential. “[T]he greater Tostan’s success, the more uncomfortable Molly became with taking the credit herself; she was adamant that the achievements were due only to the efforts of villagers,” Molloy writes.

Unlike the self-promoting social entrepreneurs and instant-gratification-oriented saviors who populate much of the literature on American social change efforts in Africa, Melching takes care to build credibility within the communities where she works. Using her position of relative privilege, yet drawing on the guidance of local mentors, she develops support for women’s groups by building trust among religious leaders and village chiefs. One of her rural mentors offers an insight that captures her style of leadership: “[A] leader is like a Fulani cow herder … [S]ometimes he will lead the herd from the front, sometimes he will remain in the middle and be part of the herd. And sometimes he will remain behind, allowing them to move forward on their own, following their lead.”

Another ally of Melching’s, a village chief named Demba Diawara, helped Tostan to develop a method that later came to be known as “organized diffusion.” He would walk from village to village, engaging in dialogue with community members and mobilizing local social networks to support an end to female genital cutting. “[E]ven if you know what the answer is, and you know what is right, you must let people discover it themselves,” Diawara says to Melching. He and other local leaders—people like Oureye Sall, a former traditional “cutter” who now works with Tostan to promote women’s health—know best how to root out the problems faced by their communities.

However Long the Night suffers from some of the flaws that often mark books about do-gooders from the developed world who venture into the developing world. Molloy uses clichés (“stifling,” “crowded,” “bustling,” “primitive, “exotic”) to describe Melching’s initial experience of Senegal. “[W]ith no electricity or running water, Molly felt as if she had traveled back in time, arriving in a world without history,” Molloy writes. At one point, in an especially condescending turn of phrase, she describes Senegal as a combination of “refined French culture and third world need.” Such language oversimplifies Melching’s experience and detracts from her story. Fortunately, however, Molloy generally keeps her focus on the work that Melching and Tostan have done in Africa.

In their efforts to improve people’s lives at a grassroots level, Melching and her colleagues at Tostan have prevailed amid many obstacles—including discomfort, derision, loss of funding, and even death threats. The painstaking work of true social change requires just that kind of resilience.

Read an interview with Molly Melching.

Read another review of However Long the Night.