An Islamic militant walks into a bar and hires a stripper. One week later, he blows himself up. Does his act count as terrorism? According to a West Point Combating Terrorism Center study, over 85 percent of the “Islamic” militants in their dataset had no formal religious education. And according to a United Nations Counter-Terrorism Centre study, only 16 percent even believed in the idea of establishing an Islamic State or caliphate in the Levant. Moreover, if we look to the data on how terrorist groups end, the Global Terrorism Index, an analysis of 586 terrorist groups that operated between 1970 and 2007, found that repressive counterterrorism measures enforced by military and security agents achieved the least success with “religious” terrorist organizations—contributing to the demise of only 12 percent.

How can humanizing counterterrorism transform the conditions that lead to violent extremism and enable greater peacefulness? What urban policies have made the Belgian city of Mechelen resilient to radicalization—despite having the largest Muslim population in Belgium? Why does Morocco rank among the countries suffering “no impact from terrorism,” while Moroccan immigrants in Europe are among those most susceptible to violent radicalization? How did love demobilize the ruthless terrorist group Black September? These are some of the questions Compassionate Counterterrorism: The Power of Inclusion in Fighting Fundamentalism answers in a sober yet optimistic analysis of how we can transition to a post-fundamentalist future.

The following edited excerpt from Chapter 12: Show Me The Money, highlights examples of development-based interventions that have successfully deterred terrorist recruitment, and the endemic challenge impeding the scale and impact needed for preventing and countering violent extremism (P/CVE). — Leena Al Olaimy

***

WHEN MUHAMMAD YUNUS, the father of microfinance and founder of Grameen Bank, was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2006, it validated the proposition that peace is inextricably linked to poverty and that poverty is a threat to peace. I am uncertain as to whether many people would have consciously made that link without hearing his acceptance speech. In it, Yunus applauded the world’s moral audacity for adopting a historic millennium development goal in the year 2000—to halve poverty by 2015. However, one year after the turn of the century came September 11, followed by the invasion of Iraq— effectively derailing the world from the pursuit of this dream.1

At the time of Yunus’s speech, the US alone had spent over US$530 billion on the war in Iraq. To put this number in perspective, today, Iraq is seeking less than 20 percent of that amount—US$88 billion—for post-war reconstruction. To date, it has been allocated only US$30 billion.2 In his speech, Yunus continued by saying, “I believe terrorism cannot be won over by military action. . . . We must address the root causes of terrorism to end it for all time to come. I believe that putting resources into improving the lives of the poor people is a better strategy than spending it on guns. . . . The frustrations, hostility and anger generated by abject poverty cannot sustain peace in any society. For building stable peace we must find ways to provide opportunities for people to live decent lives.”3

Although poverty doesn’t cause terrorism, as Chapter 5 illustrates, we should recognize that a vacuum of hope and dignity among young people makes them considerably more vulnerable to terrorist recruitment—especially when ignited by flagrant injustice.

Terrorism Accelerator

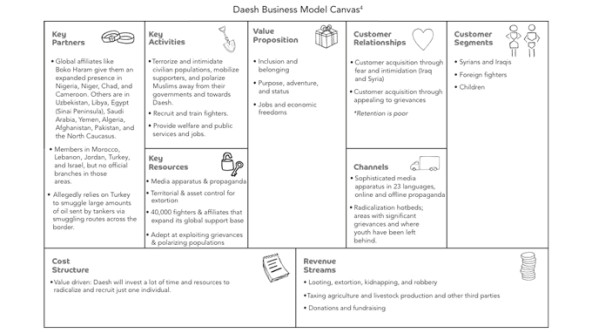

To borrow from the entrepreneurship space, if we were to map Daesh’s (ISIS) business model on the ubiquitous Business Model Canvas (Figure 1), our Customer Segments would be Syrians and Iraqis—for obvious geographic reasons—and foreign fighters, who are predominantly youth traveling to join the militant group from other countries and children who are often recruited against their will.

To win its differently motivated Customer Segments, Daesh deceptively promises community and belonging, meaningful purpose, religious purification, and adventure and status, along with financial incentives. Although its talent retention is poor, pervasive grievances massively boost its talent attraction and recruitment efforts. Comparatively, traditional counterterrorism interventions—which may cut off terrorist financing and revenue streams—don’t satiate the needs of recruits whatsoever. More ominously, these tactics reinforce Daesh’s polarization strategy and mirror the group’s terrorization of civilian populations.

(Figure 1: Daesh Business Model Canvas)

Essentially, through military brute force, we are trying to win our Customers by bombing them, killing their families, humiliating them, denying them dignity, exacerbating unemployment and a tenuous economy, instigating socioeconomic and political flux, and failing to acknowledge—let alone properly compensate for—the collateral damage. Even if one terrorist group is militarily weakened, by not neutralizing existing grievances, we simply allow new groups to enter the vacuum and present their alternatives to the disaffected. In short, our current approach is a violent extremism incubator and accelerator.

On the other hand, if it’s not already clear, a robust counterterrorism incubator and accelerator needs to eliminate the grievances and injustices leveraged by extremist groups—not amplify them. And it should present alternatives that fulfill the Value Proposition presented by Daesh, such as providing opportunities for inclusion and belonging, dignity, economic empowerment, and purpose.

Fighting Fundamentalism Through Farming

It took one social entrepreneur in Nigeria several years to earn the trust of a demographic susceptible to extremism and unexpectedly seed peace through farming. I came to learn of Kola Masha through the Skoll World Forum for Social Entrepreneurship at Oxford University—an annual gathering where changemakers, Nobel Laureates, social scientists, and redefined “billionaires” with the intention of impacting one billion people come home to a like-minded and like- hearted tribe. At this “Davos of Social Innovation,” notable personalities like Muhammad Yunus, Richard Branson, and the late “King of Data” Hans Rosling have been among the forum’s delegates.

Masha—whose social enterprise Babban Gona won the distinguished 2017 Skoll Award—asks rhetorically, “Why has it become so easy for disgruntled individuals to raise a mini-army? Because young people have limited economic opportunities.”18 According to Masha, youth in Nigeria face a staggering 50 percent unemployment rate—which means one in two young people are unemployed. One might wonder, however, when Boko Haram is offering cash and a motorcycle, how does Masha get at-risk youth to ditch their symbols of status for tractors?

It turns out youth are much more practical. Most would prefer to stay in their hometowns, he tells me.19 They only leave in pursuit of economic opportunities, which are largely absent in rural areas. So to dissuade the youth from leaving to join insurgencies—which is typically their last resort—Masha arms the young men and women with the ability to earn more than enough to take care of themselves and their families. Babban Gona’s business model is designed to dramatically increase farmer income through crop yield optimization, microcredit, and economies of scale. Although it’s difficult to capture specific data on former extremists who have renounced Boko Haram—not something they would want to openly divulge, I am told—Masha narrates a story of one of his members that encapsulates the downwards spiral that has entrapped so many Nigerian youth.

In search of better opportunities, this young member left his community to become a motorcycle taxi driver. City life was rough. He endured days of hunger, waiting in the rain for customers and in constant fear that his only asset—his tattered motorcycle—would be stolen or simply break down. And many like him indeed plummeted into destitution, making them the perfect recruits to fill vacancies as motorcycle getaway drivers for Boko Haram’s merciless kidnappings and robberies. Instead, through the alternative Babban Gona provided, this young man was able to turn his life around in two years. He has earned enough money to purchase his own retail store, he bought his mother three goats, and now he owns not one motorcycle but two. His dignity dividend is priceless.

Initially, Masha’s greatest challenge was trust building. It took several years, but once Babban Gona reached an inflection point—proving its model, and earning the social license to operate—growth accelerated. Babban Gona doesn’t screen its members by age and is open to everyone, but around 45 percent of its 20,000 farmers are under the age of thirty-five, and it has helped increased their net income by three and a half times. The social enterprise has also disbursed 16,000 profitable loans with a remarkable 99.9 percent loan repayment rate.20

Estimated numbers of Boko Haram militants vary, but they run in the thousands. Masha, meanwhile, is targeting an army of 1 million farmers by 2025 at a cost of less than US$1 billion—or US$1,000 a person.21 Once a community has succumbed to extremism, it can be very difficult to solve, resulting in the loss of at least one or two generations before restabilizing, Masha tells me. By targeting communities teetering on the border of violent extremism, Masha’s organization creates an economic buffer that also maintains both human and food security.

As with most impact trailblazers, Masha’s current formidable challenge is funding. Today, in the conflict-affected and food insecure region of North-East Nigeria, it is virtually impossible to get investments from the private sector, and government interventions are very costly. Had investments in preventative initiatives like Masha’s been made ten years ago, they would have constituted a fraction of today’s security budgets and the opportunity cost of economic decline.

Investing in Peace and Prosperity

Entrepreneurship promotion barely skims 1 percent of the US Foreign Aid budget, according to calculations by Steven R. Koltai.24 In a Harvard Business Review article, Koltai argues in favor of allocating greater amounts of overseas assistance towards entrepreneurship, noting that job creation promotes stability.25 Merely the awareness and visibility of such initiatives can increase the hope and confidence of local populations—dissuading their support for extremist groups. Studies have suggested as much; the visibility of USAID programs appears to be correlated with people’s increased confidence in their government (and positive views of the US) and with decreased support for extremist groups. For example, in Nigeria, 78 percent of people who said USAID-funded programs were “visible” or “very visible” reported being “confident” or “very confident” in their government. Of those who said they were con dent in the government, 87 percent were unsupportive of extremist groups.26

Unfortunately, current meager allocations of foreign aid are dis- proportionately focused on supporting micro and small enterprises, rather than larger companies with the wherewithal to employ thousands, or for-profit social enterprises, like Babban Gona, that stabilize economies and markets and reinforce long-term incentives for maintaining peace. It’s a bit of a catch-22 because, as Masha rightly notes, who would invest in a North-Eastern Nigerian venture fund? Or, for that matter, a Syrian high-impact entrepreneurship accelerator?

Businesses don’t appear to fully appreciate the mutually beneficial roles they can play in maintaining peace. Nestle, for instance, is Babban Gona’s biggest client. In creating shared value—that is, driving profits through serving societal or environmental needs—Nestle helps Masha’s farmers increase their incomes by enhancing their crop yield and quality, which are important agricultural inputs for the Nestle supply chain of nutritional products. I cannot help but wonder, however, why they are not measuring the impact these efforts have on maintaining peace and security and the averted cost of business disruptions caused by violence and volatility. If they did, it could provide a powerful business case and incentive for other corporations to view investments in peace as worthwhile economic endeavors.

While the Shared Value approach of driving economic competitiveness through serving societal needs is nascent in the peace-building field, its potential is already being explored by international nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) like Mercy Corps and Search for Common Ground (Search)—a 2018 Nobel Peace Prize nominee and, in full disclosure, a former client of mine. In Sri Lanka, for instance, Search is facilitating the intermarriage between business-friendly and people-centered solutions in urban settings. Search convenes small businesses; large enterprises like luxury housing developers, hoteliers, and the banks funding such projects; and young people, civil society, local communities, and government. Together, they address the vulnerability and division engendered by this rapid urbanization.

With billion-dollar projects looking to commercialize the beautiful Indian Ocean island of Sri Lanka, many people are left displaced. And the businesses involved seem totally indifferent to local communities; people are uprooted and relegated to lower-quality housing at an accelerated pace, increasing friction between the local people and the incoming businesses. We know that tourism’s contribution to GDP in countries with terrorist attacks is half that of countries without terrorist attacks.27 So in Sri Lanka, recognizing that violence and insecurity are the nails in the coffin of a burgeoning tourism sector, the stakeholders work together to improve the lives of young people and address their grievances through a business model that has social capital. This means that the business model is financially sustainable while earning the social license to operate in the long-term.

While it’s too early to capture meaningful data or success metrics, the beginnings are promising and those involved in the project have noted that in some ways, Search is offering Sri Lankan youth what Daesh claims to offer: a sense of agency and purpose, status, and a meaningful opportunity to engage in improving their individual and societal circumstances.

When I listen to these challenges, one thing strikes me. Search is a Nobel nominee, while Masha has an MBA from Harvard, a Masters in Mechanical Engineering from MIT, and a Skoll Award. And they—like so many social entrepreneurs and positive-change agents—struggle to prove their interventions pay off and are worthy of greater resource allocations. One can only imagine the frustrations of the less globally connected. And whereas military interventions don’t need to prove efficacy to merit funding, the social sector struggles to prove that its interventions make a difference, while frugal and short-term funding cycles make this a largely unattainable ideal. When one considers the comparative return and social return on investment between soft and hard power interventions, it becomes clear that we need to reevaluate the economics of peace.