(Illustration by Taslim van Hattum)

(Illustration by Taslim van Hattum)

Power, and the lack thereof, is the fundamental cause of inequity, in communities around the world because it maintains and holds those inequities in place. For the many foundations focused on addressing racial, social, and economic inequities, therefore, achieving transformative change means shifting power to the people most impacted by these inequities. But while many foundations are now focusing on building power within communities, funders still grapple with defining and measuring power, and with the question of how best to support community power building.

A report I developed on the role of prosecutorial campaigns in mobilizing and engaging communities of color based on a set of case studies conducted several years ago led me to develop what I call a “power building framework” that may help address those questions. The case studies were each told through the lens of the organizing groups: The People’s Lobby and Texas Organizing Project. The framework emerged empirically from interviews with grassroots organizers and their partners engaged in campaigns to build community power through the election of reform-minded district attorneys (DAs) in two counties, one in Illinois and one in Texas. I created the framework to understand the case study data related to the work organizations conducted leading up to the elections and also related to the work organizations conducted after their candidates won.

After a brief explanation of how organizers and their partners in two counties constructed their electoral campaigns to build power and to hold the elected DA accountable, I’ll provide an overview of the framework, with the goal of informing grantmaking strategies that support organizations building the power needed to advance structural changes that lead to greater equity and justice.

Building Power Through Elections and Beyond

Efforts to elect prosecutors who support criminal justice reform began in earnest in 2016 with Kim Foxx running for DA in Cook County, Illinois, and Kim Ogg running for DA in Harris County, Texas. While these counties had diametrically different political contexts, they shared similar challenges, including a well-funded police union opposition whose narratives equated safety with tough-on-crime strategies. Both counties also experienced movement moments highlighting the systemic racism and injustice of the criminal legal system: In Illinois, the Chicago police killed Laquan McDonald resulting in social uprisings. In Texas, police arrested Sandra Bland for failing to signal a lane change, and she died in a nearby Walker County jail cell.

Organizers in both counties used the DA races as a means to channel community pain and anger toward systems change and justice. Organizers led with the issue of criminal justice, describing their endorsed candidate as a vehicle for reforming the system. They used the election to organize and engage community members around their criminal justice priorities. Instead of portraying the election as a popularity contest between the DA candidates—or, for that matter, between presidential candidates Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump—they characterized the electoral campaigns as a means to advance longer-term systems change goals targeting the criminal legal system and as part of an ongoing struggle for power.

Both campaigns to elect reform-minded DAs consisted of a very broad, diverse collection of organizations led by grassroots organizing groups. The efforts required a wide range of capacities, skills, and knowledge:

- Civil rights, policy advocacy, and legal advocacy organizations provided data, research and analysis, and technical legal and policy support both during and after the campaign to inform the policy agenda and help organizers and communities understand and navigate the criminal legal system.

- Labor unions were pivotal in the effort to turn out the vote and were one of the few partners, along with some of the organizing groups, that could legally engage in electoral activities.

- National organizations provided communications, polling, and social media support.

- Immigrant rights organizers expanded the base of support through a shared understanding of the criminal legal system, and of the immigration and detention system as the flip side of the same coin.

Organizing groups were the central throughline, educating community members on the role of the DA in the criminal justice system, engaging community members in the election, and, once elected, holding the new DA accountable. These organizers also maintained a broader vision for the work: fundamental systems change to the criminal legal and immigration systems by addressing the structural and racial drivers of incarceration and detention.

The organizations also had shorter-term goals that included bail reform and reducing the prison population. In Harris County, a coalition of organizations developed a policy agenda that included reforms to the bail system, drug diversion, police accountability, debtors’ prison, youth justice, ending collaboration with ICE, and implementing cite and release. They used the candidate endorsement process to ensure candidates aligned with their policy goals, as well as committing to work with the community if elected.

The election of Kim Foxx and Kim Ogg was just the start of the work. The elections demonstrated the ability of community organizing groups and their partners to sway elections, which helped them build the power they then used to hold the winning DAs to their pre-election commitments. Post-election, organizers pivoted to monitoring and accountability, and to the difficult complex work of systems change. In Cook County, organizers created a co-governing strategy with the DA to ensure ongoing engagement with the community and the advancement of community priorities. In particular, the DA agreed to regular communications and meetings with organizers, public forums, and providing increased systems data transparency that organizers could use to track progress on reforms and community goals. In Harris County, organizers had targeted multiple county agencies and systems by electing multiple leaders—the Mayor, Sheriff, and DA—to create a cohort of decision makers with a shared agenda, who could each make advances from their respective positions while providing support to each other. These governing strategies had different approaches, but a shared goal of delivering direct material benefits to their communities.

The strategies and the capacities organizations needed for this kind of monitoring and accountability differed greatly from what was needed for the electoral campaign. That second phase of work required a deeper understanding of the system and an ability to develop inside-outside strategies to both hold the DA accountable and provide the DA with support when needed. While legal advocacy and policy organizations helped educate community members on the system—such as by training court watchers to collect data on bail hearings—organizing groups used power mapping to identify the power brokers within the system so they could target them to advance specific goals. This work pointed to the need to elect reform-minded judges during the next election cycle.

Grassroots organizing groups were the central thread throughout the various campaigns and strategies for several important reasons. First, some of the leading organizing groups were also 501(c)(4) organizations and could overlay electoral organizing onto their ongoing year-round organizing to expand their base. Second, organizing groups built community leadership within their base to engage with the DA and to advance community policy priorities. Third, their (c)(4) capacity allowed organizations to endorse the DA candidate and garner her commitment to their policy agenda, which put teeth in the accountability work. Finally, organizing groups focused on building power as opposed to achieving independent electoral and policy wins.

In both Harris and Cook counties, these initial campaigns led to important systems reforms and further electoral wins. For example, as part of their Right2Justice campaign, organizers in Harris County helped elect a slate of 17 African American women to judicial seats along with Lina Hidalgo, the first woman and first Latina, as a Harris County judge. They also expanded their campaign to support the election of reform-minded DAs in Dallas and Bexar Counties. In Cook County, groups made advances in bail reform, prosecutorial discretion, and data transparency leading to a 20 percent decrease in incarceration in Ogg’s first term in office.

Building The Power Building Framework

Stepping back and looking at the entirety of the work in Texas and Illinois over multiple years, six themes emerge.

1. View achievements within the context of a long-term agenda.

The achievements in Cook and Harris counties are not independent campaigns but part of a broader, ongoing, long-term strategy. The policy and systems change achievements would not have been possible without the electoral work that built the relationship with the DA candidates, which grew the community organizing groups’ political power that they then leveraged to hold the DA accountable.

From this perspective, system transformation does not happen with a single action or campaign. Organizations must grow the capacity to win campaigns as well as the ability to analyze structural power. Too frequently, campaign strategies begin and end with a focus on achieving a single policy and/or electoral win, but lawmakers can repeal, defund, or significantly modify policies during the implementation process. Decisionmakers need both support and accountability to ensure this doesn’t happen. A comprehensive strategy considers the full life cycle of the goal, the varying strategies and capacities needed to achieve it, and how the strategy is positioned within a longer-term agenda.

2. Create a diverse ecosystem of organizations to support and advance community goals.

Although grassroots organizing groups led the work and held the vision, they did not and could not succeed alone. A diverse ecosystem of organizations provided a range of important skills, including legal, advocacy, policy analysis, polling, research and data, communications, and (c)3 and (c)4 electoral strategies. These supporting partner organizations provided expanded tactical skills, options, and opportunities and enabled organizing groups to pivot from the electoral campaign to the difficult and more nuanced work of accountability, co-governing, and systems change.

Working together, these organizations formed a collaboration that was greater than the sum of its parts. Infrastructure is a critical element that facilitated their collaboration and enabled them to connect to the various capacities needed to implement their strategies. Fundamentally, infrastructure serves as the connective tissue that links organizations to each other and to information and resources and helps them build and scale power.

3. It’s not just about the wins.

Both the Harris and Cook County campaigns successfully elected reform-minded candidates but that was never the only goal. The campaign for DA was only the first foray into organizing around a prosecutorial race for both counties. While a loss would have been disappointing, the organizing groups saw the campaign as an important opportunity to expand and engage their base and to build their capacity to work on the criminal legal system.

An overemphasis on policy wins obfuscates other important shifts and changes, because these electoral and policy outcomes, in and of themselves, are not the end goal. Successful policy wins require ongoing monitoring and advocacy for their effective and appropriate implementation. Successful candidates need to be held accountable to the communities they serve. Wins and losses are both potential stepping stones to build upon. For example, organizations in both counties shifted the tough-on-crime narrative to a community safety and reform narrative, forcing DA candidates to run on a reform agenda and work with communities to achieve that agenda.

4. Build power to leverage towards the next goal.

By expanding and mobilizing their base and demonstrating that they could win elections, organizers used the DA election to build power and then used that power to hold the DA accountable. Organizing groups also institutionalized their power through co-governing strategies and the ongoing engagement of the base that brought communities to the decision-making table and in dialogue with the DA, leveraging their power again in subsequent actions for policy reforms.

Focusing only on electoral wins can squander the power gained through the wins, while focusing only on accountability may be less effective at institutionalizing power without the electoral teeth to hold officials accountable. The outcomes in Harris and Cook counties reflect how work that includes implementing mass mobilizations, campaigns, elections, and litigation can build power and how that power is then leveraged toward the next campaign or strategy forming a cycle of power building. Each cycle represents a campaign or action. In this way, communities build power incrementally, intentionally, and strategically with each cycle. Community organizations then wield power in ongoing cycles toward long-term goals. In other words, power is both a means to achieve goals and an important end in and of itself.

5. Power is capacity and influence.

Normally, case studies would end with the victory and the accomplishments. However, community organizing groups achieved more than electoral, policy, and systems change wins, and even more than power and narrative shifts: these organizations expanded their capacity and influence, which is the very definition of power. They expanded their capacity to work on criminal justice issues by increasing the number of community leaders, increasing organizations’ knowledge about and ability to address criminal justice issues, bringing in new partners and collaborations, and expanding the base of support across regions of the state. There was also evidence that community organizing groups and their partners had more influence: community organizers successfully ran for local public office, new community leaders emerged, decision makers reached out to collaborate with organizing groups, and some decision makers viewed them as a threat. Indeed, recent attempts by the Texas legislature to undermine local elections authority in Harris County indicate that the legislature recognized the influence of these organizing groups.

6. Continuing challenges to co-governing and power building.

Despite the successes, community organizing groups and their partners in Cook and Harris counties faced challenges as they shifted to co-governing strategies. They missed some important opportunities because they initially lacked sufficient systems understanding and sufficient understanding of the role and purview of the DA, missteps which led to increased systems learning and a recalibration of strategies to co-govern.

It is important to note, after all, that not every campaign will lead to an expansion of power, especially if there is no embedded strategy to build it. The organizations I focused on were intentional and thoughtful in their engagement and power building goals, and demonstrate what can happen if organizations implement with an intent to build power, a willingness to integrate new learning, and an ability to recalibrate strategies when something isn’t working. They fundamentally understood that a single electoral win or policy change would not achieve their vision for systems transformation. They also understood they needed sufficient power to go up against powerful police unions and deeply rooted tough-on-crime narratives. The work is ongoing with both missteps, losses, and progress.

The Power Building Framework

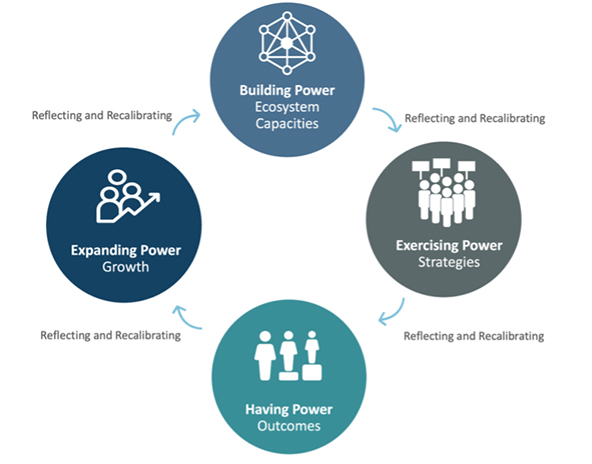

I used the above themes to create the power building framework in an attempt to simply describe how power is built, leveraged, and expanded through cycles of work, over time.

- Building Power. Power building relies on an ecosystem of diverse organizations that each contribute a range of important strategic capacities. Those capacities enable organizations to implement sophisticated campaigns, strategies, and actions. Grassroots organizing groups sit at the center of the ecosystem because they play a critical role in building a base within the communities most impacted by inequities and they directly engage those communities in addressing those inequities. Power is built with and by communities, not for communities. The power that resides in the ecosystem is nascent until it is leveraged. A healthy ecosystem with a range of capacities and connective infrastructure creates readiness, enabling organizations to act on windows of opportunity or to respond to opposition and external assaults of all variety.

- Exercising Power. The ecosystem of organizations exercises and leverages power through a variety of campaigns, strategies, and actions. The specific tactics, strategies, and targets organizations can deploy depend on the range and diversity of capacities available in the ecosystem.

- Having Power. The outcomes of the campaigns and strategies are varied. These outcomes include policies, systems change, electoral wins, and narrative shifts. However, they also include losses. And not all wins are the same but wins that advance greater structural change can build more power.

- Expanding Power. Power is both capacity and influence. As Stephen Lukes describes, there is both hidden power and visible power. Hidden power reflects the increased capacity and agency in individual community members and leaders, the individual organizations that engaged in the campaign, the collective ecosystem of organizations that collaborated on the campaign, and the potential expansion of the base and the ecosystem across geographic regions. Visible power reflects the increased influence, credibility, and legitimacy, which provide individuals and organizations with increased access to and involvement in decision-making.

Implications for Funders

For funders, this power-building framework has obvious implications for evaluation and learning and for grantmaking strategy.

(Illustration by Taslim van Hattum)

(Illustration by Taslim van Hattum)

Funders who want to focus on the root cause of inequities must understand and address the power that creates, entrenches, and holds those inequities in place. To do that involves analyzing where power resides, who has power, and the relative power of the opposition (as well as the historical and racial underpinnings of current power structures).

The framework also highlights the importance of funding for the long-term, and building sustainable infrastructure beyond campaigns, policy, and electoral wins and losses. The electoral successes in Georgia during the 2020 and 2022 elections stem from the infrastructure that grassroots organizing groups built with their partners over the last decade. Grant makers who want to influence real change must focus on building lasting, durable power.

Finally, philanthropy’s increased focus on grassroots organizing as a means to build community power is important and necessary but it is not sufficient. Significant organizing capacity needs to expand, but organizers and communities cannot take on structural racism alone. As demonstrated by my case studies, and highlighted in the framework, it takes an ecosystem of organizations to build power. Philanthropic priorities and strategies often contribute to a fragmenting of the progressive field. While supporting issue campaigns may help advance specific policy goals, and even lead to short-term policy wins, it does not build enduring power that brings about structural change. No single organization or foundation alone can build sufficient power to achieve and sustain significant structural change. It takes an ecosystem of diverse organizations to build and exercise power. It also takes an ecosystem to build and scale community power. If funders want to influence true change they must collaborate in support of multi-issue, multi-constituency ecosystems that contribute to building power in the communities they hope to support.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Gigi Barsoum.