(Illustration by iStock/masterSergeant)

(Illustration by iStock/masterSergeant)

If you’ve been working in philanthropy for longer than a week, you’ve probably come across a report, analysis, or opinion piece about systems change. It’s everywhere. There are peer groups, conferences, webinars, blogs, and even schools dedicated to systems change. And there are as many definitions, theories, and conceptual frameworks of systems change as there are articles written about it.

But, as the recently released evaluation of Rockefeller Philanthropy Advisors’ Shifting Systems Initiative (SSI) suggests, it’s an overused and poorly understood concept in philanthropy. The report indicates that the increasing attention to it is both good and bad. More funders are talking about systems change and considering supporting it, which is good. On the other hand, the more voices that join in, the “messier” the field becomes. This messiness has yielded a degree of inaction, frustration, and resentment that has prevented greater uptake from more funders. According to the evaluation, there’s been a lot more “talk than walk.”

As a frequent participant in funder calls and donor working groups, our team at the Roddenberry Foundation has seen this “systems change fatigue” up close and personal. Many funders have either ignored the field completely because of its complexity or indulged so much in the complexity that it has hampered action. It often feels like the time we’ve spent defining, describing, and unpacking what systems change is and how to approach it has gotten in the way of our ability to fund it.

In 2020, our understanding of systems change shifted in a wholly unexpected way. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, we launched the +1 Global Fund, a network-based platform that leverages peer nominations to discover small, earlier-stage organizations in the Global South. In short order, we began to notice that—independent of region or issue area—many locally led, often very small initiatives were influencing entrenched systems. This came as a surprise and, with it, came the realization that the field has seemingly overlooked and undervalued the role small organizations play in systems change.

Are you enjoying this article? Read more like this, plus SSIR's full archive of content, when you subscribe.

Based on our experience, making funding systems change easier and more accessible to more funders requires that funders redefine how systems change occurs and who leads it.

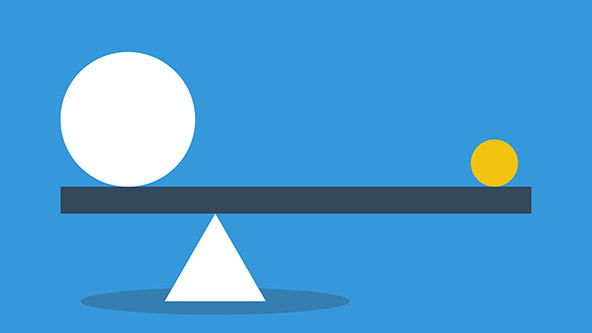

The Bias of Scale

An unmistakable takeaway from the SSI report is that there are few well-defined or commonly agreed on parameters or dimensions in the systems change field. One of the casualties of this is the perpetuation of core assumptions that are unhelpful at best and at worst a detriment to the field. The most pernicious one is the narrative regarding small, locally led organizations and our low expectations of them (which is not exclusive to the social change space).

We often hear that small organizations can only provide direct services or are too resource-starved to work toward a long-term end goal. These arguments usually hinge on the notion that systems change work belongs in the domain of large organizations with sizable budgets (from the Global North). Exhibit A includes the case studies that consultants, practitioners, and funders most often cite, which are overwhelmingly of large, well-staffed organizations with budgets north of $5 million (and many multiples beyond that).

Is this a failure of imagination? Or, given the enormity of systemic issues, is there the (mis)perception that the field needs an equally yoked response from substantial institutions, and nothing less will do? Or, as the SSI report alludes to in reference to funder inaction, is it a result of philanthropy’s “mental models about change; assumptions about impact; and undervaluing of indigenous/homegrown Global South knowledge”? The end result is that the systems zeitgeist, perhaps without necessarily intending to, has made scale a precondition for success in systems change.

We’re certainly not the only ones to notice this, and others have made persuasive arguments for looking beyond the usual suspects, but the message is almost always the same: If you’re a funder interested in systems change, write a check to a big organization. We’ve participated in dozens of calls, attended workshops, and devoured much of the literature, and we keep running into this bias. It’s hard to avoid the conclusion that the dominant mental models within philanthropy—“go big, or go home”—are strongly influencing the systems change discourse.

Small but Mighty Systems Change Makers

We launched the +1 Global Fund using trusted networks and peer nominations to find and support locally led organizations in the Global South. Since then, we’ve awarded grants to hundreds of organizations with budgets of less than $500,000 in dozens of countries. The organizations are improving water and sanitation access, education quality, food security, and health equity, and a large majority take systems change approaches to their work.

As a collaborative effort with multiple funding partners, we have regular conversations with foundations from across the globe. When we describe the types of organizations we’re discovering, they often express disbelief. “They can’t really be implementing systems change” is a common refrain. It’s as though smaller organizations’ versions of systems change are good knockoffs—they look like the real thing but clearly aren’t.

Over the past three and a half years, we’ve seen smaller, locally led organizations that are driving system change with all the hallmarks of their larger peers. These include a deep understanding of the system of concern, a clear vision for how those holding the problem in place need to shift and a sound strategy for making those shifts happen, and a collaborative approach that engages multiple stakeholders and accounts for diverse agendas and perspectives. Consider just five recent awardees in sub-Saharan Africa with budgets of less than $300,000:

- Pathways Policy Institute, based in Nairobi, Kenya, works to create safe spaces for youth advocates and communities to both engage with and influence public health and environmental policies through research, training, and capacity strengthening.

- In Uganda, the 40-plus members of Food Rights Alliance mobilize and organize communities for collective action to advance the cause of ending hunger and malnutrition. Together, they address barriers to safe and healthy diets through capacity building, strategic collaborations, and advocacy for increased resources, improved policies, and better government accountability.

- The Zimbabwe Land and Agrarian Network brings together civil society organizations, traditional leaders, farmers, local authorities, and other groups in the land and agrarian sectors. Together, they address food security challenges related to climate change, land tenure, and agriculture productivity that smallholder farmers face.

- Shahidi wa Maji facilitates sustainable and climate-resilient water resource management and WASH services in Tanzania by partnering with civil society organizations, alliances, networks, journalists, and communities to promote the sustainable management, equitable access, and efficient use of water resources.

- Across Africa, Guzakuza connects and supports women facing food system challenges. Through mentorship programs, business incubators, advocacy, and advisory committees, Guzakuza helps its members build and grow agribusinesses, gain access to hard-to-reach markets, and advocate for farmer-friendly policies.

Zooming in on all five organizations, we see that each has a small budget. All are targeting the deeper root causes of the problem, rather than the symptoms. Each acknowledges the complexity of the systems they are influencing and the people in it. And all are ambitiously intent on seeking fundamental, lasting change.

Field-Wide Benefits of Supporting Small Organizations

The SSI report offers multiple recommendations for improving the field, and we’d like to contribute another: support smaller, locally led organizations to unlock their incredible potential to influence systems. We suspect it’s easier to track and analyze larger organizations that are of greater interest to the field, but we nevertheless see a missed opportunity. By ignoring them, funders keep small, locally led initiatives in funding traps that, paradoxically, shackle the full system change potential of their initiatives and of the field at large.

Rethinking the role of small organizations can generate:

- A bigger pipeline. A broader pool of organizations to fund, support, and draw lessons from should be a natural goal. Needless to say, there are exponentially more small organizations in the world than large ones. There’s no good reason to dismiss an organization employing strategies that are aligned in every way with a systems change approach but are still small. Rather than wait for them to grow and prove their worth as systems change makers, funders can nurture and support them while building a robust pipeline now.

- More action. Right now, the dominant narrative driving the systems change field is akin to the search for the Javan rhino; the field is having a hard time finding an extremely rare rhino and feels disappointment when it spots a white or black one. Rhinos aren’t identical and the rarer one is worth looking for, but if the field is too precious and wedded to one parameter in its search, it’s going to miss out on some unbelievable sights. Demystifying and broadening the field’s idea of what makes a systems change organization will lead to a greater diversity of approaches, more learning, and a shift from “talk to walk.”

- More funding. For smaller foundations interested in systems change, the choice—whether funders are aware of it or not—has been between making big grants to large organizations or doing nothing at all. Broadening the pool of grantees to include smaller organizations will increase the number of funders for whom making a smaller grant is more aligned with their giving capacity. Smaller grants to smaller organizations also de-risks the uncertainty inherent in systems change, which will also increase the number and amount of funds directed toward it.

- A stronger ecosystem. Growing and strengthening the systems change field means making it more inclusive of more organizations, leaders, and practitioners. Incorporating smaller organizations, and thus a broader spectrum of funders and change strategies, will lead to more active participation and a richer understanding of how to effect change. It also enables the unique perspective of small, locally led organizations—their deep understanding of local challenges and opportunities, proximity to their communities, and organizational agility—to influence the field’s thinking.

The SSI report makes the unequivocal conclusion that the systems change field is still in flux and “has not produced critical works that define the field clearly.” It also highlights the need for more diverse voices, localized efforts, and varied funding sources. As such, there’s no better time to strike. Funders have a unique opportunity to collectively expand their understanding of how to influence systems by incorporating small organizations into their discourse and funding streams. If the field course corrects now, it can build a robust, highly engaged ecosystem of system change funders and practitioners.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Lior Ipp.