(Illustration by iStock/erhui1979)

(Illustration by iStock/erhui1979)

The number of children refusing to attend school in Japan is increasing at an alarming rate. This phenomenon, known as futoko, refers to the increasing number of children who don't attend school for more than 30 days due to reasons unrelated to health or finances. According to the latest survey conducted by the Ministry of Education (MEXT) in 2022, more than 244,000 elementary and middle-school students in Japan fall into this category and face difficulties in attending school. Indeed, truancy rates have been rising across the nation for 9 consecutive years, with a 3.6-fold increase among elementary school students and a 1.7-fold increase among junior high school students compared to a decade ago.

The causes of truancy are multifaceted and complex. A previous MEXT survey on dropouts from elementary and junior high showed that problems with teachers and friends at school, and disturbances in daily routines caused by social media, the Internet, and gaming are among the main contributing factors. But there can be other reasons as well. “Sometimes [students] simply don't like what is being taught at school,” says Nozomi Torii, a board member of the nonprofit movie theater Ueda Eigeki. “It can also be as simple as feeling stressed about having to wear a uniform every day.”

Dropping out of school can have serious long-term consequences, including limited personal development, social stigma, and reduced employment opportunities and lifetime earnings. Young people who drop out are also at risk of withdrawing from society entirely and shutting themselves away in their rooms—a long-standing social issue known as hikikomori in Japan. Even more concerning is a rising number of juvenile suicides, with 514 deaths recorded in 2022 alone, according to the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare.

Children who refuse to go to school also influence the well-being of their family members. Some 64.9 percent of parents of children who do not attend school blame themselves, according to a survey by a Tokyo-based nonprofit organization. Feelings of loneliness and isolation were also reported by 52 percent of the respondents.

Are you enjoying this article? Read more like this, plus SSIR's full archive of content, when you subscribe.

To help address increasing numbers of dropout students, the Japanese government created a new law on educational opportunities, which came into effect in 2016. The law stipulates that national and local governments are responsible for securing educational opportunities outside of school as a measure against truancy. Under this law, school principals can count student engagement at private facilities that meet specific criteria as school attendance. Among these facilities are "free schools" run by individuals and private organizations that work in partnership with regular schools.

One innovative example of a private facility is Ueda Children’s Cinema Club, a collaborative launched by three nonprofit organizations in 2020 that utilizes the space and resources of a century-old movie theater to offer free screenings to students of all ages. In August 2020, three children and their parents attended the club’s inaugural screening of In This Corner of the World, an award-winning animated movie about a young woman’s life in Hiroshima during the Second World War. In September 2021, a local school officially recognized a 14-year-old, middle-school student as "attending school" when he watched a cinema club movie during school hours. Today, the club has 95 student members and is recognized by five schools in the region as a supplementary learning environment. One of the principals from the 5 schools argued that it has contributed to the students’ growth by “providing opportunities to experience the joy and pleasure of connecting with others.”

A Space to Learn Life Skills

Ueda is a town in Nagano Prefecture in central Japan. Nagano is a place rich in nature and history, but it also faces high suicide rates and ranks fourth in the nation in terms of school dropouts. In recent years, Samugaku, a local nonprofit that helps students (particularly those experiencing hikikomori) acquire basic life skills through a variety of experiences, noticed that the average age of enrolled students was getting younger. Together with Aidao, a local intermediary that supports nonprofits in East Nagano, and Ueda Eigeki, the aforementioned movie theater originally established in 1917 and recently saved through its establishment as a nonprofit, it began looking for ways to focus on early-stage intervention.

The entrance to Ueda Children’s Cinema Club. (Photo by Fan Li)

The entrance to Ueda Children’s Cinema Club. (Photo by Fan Li)

“When we all sat down together and discussed the idea of opening a cinema club … there was a common belief that movies can help children expand their values. Arts and culture serve to connect society and create a space that allows free expression,” says Megumi Naoi, executive director of Aidao and a Ueda Eigeki board member. “If we invite children who can’t go to school to come to the cinema instead, watch a good movie, what may happen?”

The partners believed it was essential to acknowledge that even children who appear fine on the surface may struggle with internal challenges, including the risk of suicide. Thus, they made a policy to avoid screening applicants. They also wanted to ensure that membership was free. In 2018, the Japanese government enacted a Dormant Accounts Law, which enables the government to use money in dormant bank accounts to financially support nonprofit organizations that promote welfare and community revitalization. Naoi learned about the new framework and saw it as an opportunity to apply for funding under the category of children and youth support. “Nonprofits tend to raise funds and address social issues individually,” she says. “I believe intermediary organizations have an important role to play by connecting different groups who share a common goal, and to create a big swell by involving the government and companies.” The collaboration won a grant of $175,000 from the fund to cover the club’s movie screening and operational costs for three years.

Once the project secured funding, three organizations created a stakeholder map for Ueda and neighboring cities, and started reaching out to schools, local boards of education, social workers, and experts for guidance and recommendations. Many local elementary schools embraced the concept of creating a "space of belonging" for children beyond the confines of school and family, and began distributing flyers about the cinema club on their campuses.

The group also approached other local organizations working in the youth and children field, including art houses, child care facilities, nonprofits supporting people with disabilities, and animal rescue groups. “There is an ecosystem of nonprofit organizations and small businesses here in Eastern Nagano that genuinely care about the well-being of local children and their families. This support from the very beginning is crucial for an innovative approach like the children’s cinema club,” says Torii.

In the process, they also engaged parents. Kae, an acupuncturist and mother of two children aged 9 and 7, learned about the cinema club at an Earth Day event, and now both children are members of the club. “I think it is a great experience … to meet older students, and people who work and volunteer at cinema club,” she says.

The club originally offered one monthly screening but now screens two different movies each month, including documentary, animated, blockbuster, and indie productions. The theater is also open to club members during the day every Wednesday and Friday. Students from Samugaku work at the cafe part-time while staff members of Samugaku provide counseling to club members and their parents. Middle-school and older members are invited to help with tasks like hanging posters, organizing flyers, and cleaning, and to spend time engaging in conversations about their favorite movies.

Programming also includes workshops related to film topics and conversations with filmmakers, some of which may tie into issues students and their families are experiencing. In 2021, for example, the cinema club organized a virtual interview with Nora Twomey, director of an award-winning Irish animated movie, The Breadwinner. The film tells the story of a little girl named Parvana, who lives under Taliban rule in Afghanistan. Twomey explained that she dropped out of school at age 15 and took a factory job before finding her calling in animation. When asked how she overcame those difficulties, she emphasized the importance of her mother providing her with enough time to find her own answers. Conversations like these provide members with new perspectives that are often directly relevant to their own lives. "Students who have dropped out of school often find themselves trapped in their own limited perspective, repeatedly hitting a wall and feeling desperate,” says Naoi. “Through good movies, through witnessing how others live their lives and perceive the world, these children get an opportunity to think from a different perspective and encounter different values.”

Some of the movies the club selects tell the stories of parents, especially mothers. For example, the film Kim Ji-young, Born 1982, based on a Korean novel, portrays a housewife who becomes a stay-at-home mother and later suffers from depression. “Mothers are usually the ones under stress and who take the blame [for their children not attending school]. We choose movies that can liberate them from a sense of guilt. [In addition,] children who have been trapped in their own world sometimes notice the suffering of their parents and understand their feelings from the movie about parenting. It’s like a reflection,” says Naoi.

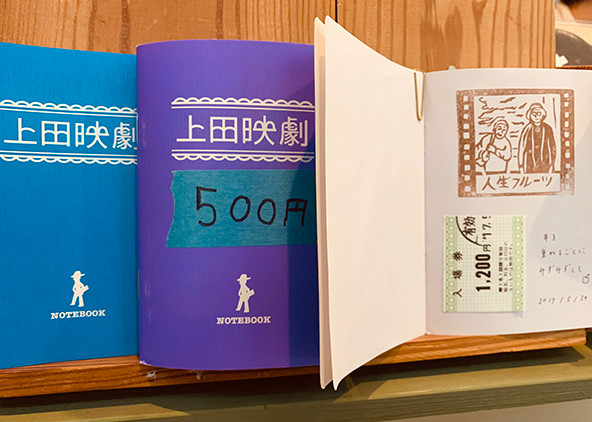

Some members of the Ueda Children’s Cinema Club collect tickets and stamps, and take notes about movies they watch in special notebooks. (Photo by Fan Li)

Some members of the Ueda Children’s Cinema Club collect tickets and stamps, and take notes about movies they watch in special notebooks. (Photo by Fan Li)

So far five schools in the region have recognized Ueda Cinema Club as a second learning space. The recognition process varies from school to school, and may involve interventions by school social workers or regular parent-teacher communications. The club staff members document attendance and submit a record sheet to each student’s school. The staff also participates in monthly meetings to engage in direct conversations with teachers.

While the goal isn’t necessarily to get students back into classrooms—indeed, some parents believe alternative learning spaces should always be an option—Naoi notes that approximately half of the club members have started returning to school at their own pace and have expressed an interest in moving forward. “You can tell that something is different from their body language; they look more relaxed, and you start to see smiles on their faces as well as on their parents.”

Building on a Good Idea

While Ueda Cinema Club is currently the only club of its kind in Japan, Marugame city in Shikoku’s Kagawa Prefecture recently reached out to Naoi for advice. The city is currently planning a new building that includes both a children’s theatre that targets kids who have difficulty going to school, and a local social welfare department office that can provide counseling to school dropouts and their parents.

In Nagano, Ueda Cinema Club has emerged as a leader in rethinking education and the role of schools. For example, it advocated for the Ueda city board of education to compile guidelines that help schools and principals determine which alternative education environments they should recognize. These guidelines, enacted in April 2023, require that alternative facilities work with "sufficient coordination and cooperation with the parents and the school.” Individuals can run alternative facilities, and no legal status is required as long as “it helps a student achieve social independence and provides support that enables smooth reintegration when the student expresses a desire to return to school.” The final decision on whether to treat participation as attendance is still made by the principals.

For Ueda Cinema Club, the next step is to provide access to more children and their family members, including students who go to school. At a symposium held by the Ueda Children’s Cinema Club in February 2023, Nagano University Professor Jun Hayasaka commented that the club has demonstrated how a theater can become a learning space and place of belonging for students that struggle to connect with others. “A movie theater is a place to enjoy culture and arts. People with different values and perspectives are watching the same film at the same time, which leads to a kind of empathy to connect to the world together. Being in the same place is extremely meaningful.”

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Fan Li.